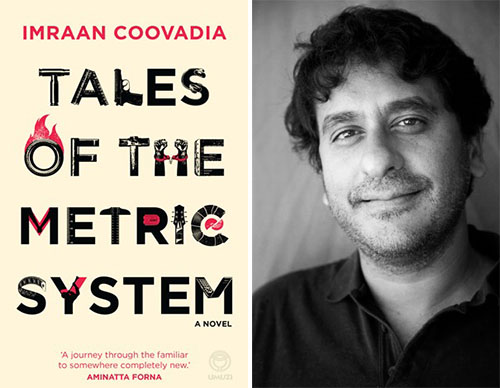

Tales of the Metric System by Imraan Coovadia, Umuzi, 2014.

Imraan Coovadia’s fifth novel, Tales of the Metric System, demonstrates beyond any doubt that the Durban-born, Cape Town-based writer is, in fact, that very rare thing: a journeyman novelist who is both ambitious and serious in his determination to provide a “history from the inside” of his time and place in the world.

“History from the inside” was the subtitle of Stephen Clingman’s influential study of Nadine Gordimer, and the implicit comparison is not far-fetched.

In this novel there is clear evidence of a literary imagination at work that, like Gordimer’s, is able to do what most SA writers can’t — bridge the periods of apartheid and postapartheid, traverse racial gulfs and write a multigenerational fiction interwoven through a range of distinctive locales.

To some extent, Coovadia goes even further than Gordimer was wont to do, creating as many as three generations of interrelated characters. This is a rare feature in our writing, by which I mean writing that is actually about SA conditions rather than just emerging out of the country.

The three-decker novel is more common in the US, where the game is much bigger, and so it’s an unusual pleasure to see the textures of SA life getting such varied treatment in avowedly literary fiction.

This is not to say that Coovadia’s novel is not readable — it is immensely so, despite the stylistic oddities that are fast becoming one of Coovadia’s trademarks: phrases like “Carla seemed to talk through a ring she didn’t have in her nose” and “Sabine put out the cigarette as if it had said something wrong”.

Such caprice of descriptive flair seems appropriate to a novel that succeeds, ingeniously, in tying up the country’s far-flung histories and key characters within an interrelated but also disparate whole in a style reminiscent of the movie Short Cuts. (It also reinvents the “Global Novel” paradigm of linked but dissimilar plots on a national scale, a profound innovation in itself.)

The book comprises a series of 10 time-and-place vignettes The book comprises a series of 10 time-and-place vignettes (about 45pp each, in separate sections) in which some but not all characters keep re-emerging. Together, these “slice of life” segues join together “historical moments” over the past 50 years or so — a “history” made up of familiar stories narrated with a kind of dry whimsy that recalls V.S. Naipaul in some of his best work.

The vignettes are vertically mined for detail of time and place, but their horizontal calculus is equally telling: 1970 (white radicals endure a boarding-school crisis in Durban); 1973 (a young black man has his pass stolen in a Durban hostel); 1979 (South Africanised descendants of indentured labourers from India claw their way up the social ladder in Phoenix township, Durban); 1985 (political exiles gather at the Soviet embassy in London); 1990 (an innocent boy is “necklaced” in Tembisa); 1995 (the now-rich, politically connected Phoenix crowd attend the rugby World Cup); 1999 (Peter Polk, a version of Athol Fugard, reproduces TRC testimony in a film production); 2003 (a version of Parks Mankahlana, here called “Sparks”, dies of Aids amid Thabo Mbeki’s denialism fiasco); 2010 (a third generation of oddly hopeful though still spotty characters watch the opening game of the 2010 soccer World Cup); and then back again to 1976, which recalls the murder of Neil Hunter, a political activist and academic styled on Rick Turner.

The novel is uncharacteristically verdant, both in its vertical and its horizontal reach, but principally in its rediscovery of characterisation. Here, again, there is both range and depth. Some of the characters are memorable “originals” — not based on historical characters — such as Ann Hunter, Samuel Shabangu, Victor Moloi and Yashdev Naicker, while others are roman à clef versions of known figures.

Meticulously drawn cameos include Uncle Ashok (a version of Schabir Shaik), the “chief”, also known as Tony Ramalho (Thabo Mbeki), Farhad (Essop Pahad), Sparks (Parks Mankahlana) and the “Old Man” (Nelson Mandela), among others.

Not only does Coovadia reach across time and place, but he is able to show real diversity within categories, so that his white figures, for example, include liberals, radicals, rough Durban musos and stiff-necked boarding-school masters, whose institutions of English manners were often the very mesh of apartheid.

Likewise, the range of black characters includes an unsparingly vigorous palette of types, starting with the creepy Mr Samuel Shabangu (Dickensian tones of narrative description, suitably updated, are richly evident here), the “one good man” guerrilla operative Victor Moloi, who is eventually betrayed by the ANC, and the perfidiously equivocal character of the “Chief” (Mbeki), whose HIV/Aids denialism leads his own most loyal supporter to his death.

Coovadia is likewise generous and unsparing in his reconstruction of the lives of distinct sets of Durban Indians under apartheid, and then again after 1994. He portrays both the cravenly upward class aspirations of the “Naidoos and the Naickers” (“fatalists, pessimists, cynics who distrusted other people and would slander and betray them“) as well as the fringe characters who define themselves against such types.

One such type is the rather beautiful, if forlorn, character of Yash. He is a doomed, broke musician married to one Kastoori Naidoo, who, like the other Naidoos, felt “injured that a man without money should penetrate Kastoori”. Reviled by his own people, he is also exploited by a white rock band, described as “pale imitators [who] played in Durban’s surf-and-turf restaurants, policeman pubs, and motorcycle steakhouses”.

As the title indicates, this is a novel that complicates the measure of things. Like the metric system’s introduction in the early 1970s in SA, which here functions as a marker of sudden change in the way things are weighed and counted, so the sheer collision of unco-ordinated forces over the half-century from 1960 to 2010 played havoc with any linear or single measure of history. One of the golden threads in this novel’s patchwork is the fact that the characters persistently steal things, as if to take revenge for the country’s sins against a more equitable accounting of things.

Coovadia’s novel shows that only a slant and skewed account (or system of account-keeping) can stand up to history – that is, no systematic dogmas, as they do not and cannot hold out, no matter where they come from or how good they sound. The skewed account, this novel implies, better adequates the rough, messy course of human doings over time. Coovadia’s version of apartheid-into-postapartheid therefore appropriately occurs within a jumbled and uneven interconnectedness in which, though universal metrics remain unavailable, the weight of love and hope – here indisputably present in the third generation of characters – is the single most important measure of all. This despite the chicanery, thievery, and merry materialism of the reality show that is contemporary South Africa.

Leon de Kock is completing a monograph for Wits University Press entitled Losing the Plot: Postapartheid Writing and the Fiction of Transition.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project