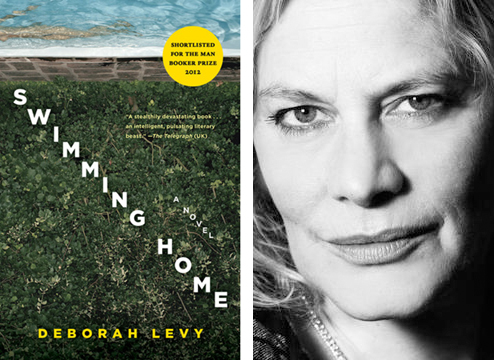

Swimming home by Deborah Levy, Faber and Faber, 2012

A mountain road: reckless driving – the consequence of rash intimacy, the restricted space of a car, the desperate (tenuous, hopeless) need for time to be reduced, for the time to contemplate a decision, an act, regret (“a pleasure, a pain, a shock, an experiment, but most of all … a mistake”) to be cut short, and for the pleading lies of hope to soothe (quieten, lessen, allay) the dis-ease of being alive, the burden of a life, the secret desire for release.

The pool: a body of water, contained, refreshing, dangerous. It is the scene of obscenity (exposure, invitation) and the scene of the crime, as yet undetermined but undeniable – instinctively recognised by the reader as the inevitable culmination of events still to be read, connected and understood but, unmistakeably, information already there between the lines, already a given.

A mountain road and a pool: the beginning and end of Swimming home and, also, the introduction of thematic concerns with restraints (constraints, limitations, confines) and freedoms, secrets and disclosures, the fragile nature of relationships, sexuality, death and mental stability. These are not exactly a comfortable set of issues to explore within what is a relatively short novel, and Deborah Levy makes no attempt to deal with these concepts in any kind of euphemistic or otherwise innocuous manner. In fact, her characters are all quite unlikeable, but it is precisely this unlikeableness which renders each of them so compelling. Multi-dimensional, pathetic, heroic, fallible, hopeless and hopeful, these characters grapple with the gamut of different levels of psychological stability so deeply entrenched (inherent) in our contemporary daily lives: psychosis, neurosis, (compulsive) obsession, depression, phobia and a whole list of other deviations best left for exploration and description in the DSM IV. But the point is, it is all implied, all neatly woven into the narrative unfolding of the opening chapters, along with the introduction of the six main characters who readers encounter within the first three pages of the novel.

This strategy of Levy’s – the sensory and memory overload – which reminds one of playwriting devices rather than of novelistic techniques (Deborah Levy is in fact a renowned playwright), serves to mimic the psychological and emotional overload of the characters and the burden (weight, affliction) of this excess on the human condition. Levy foregrounds the different mental, emotional and cognitive states we continuously have to merge, dissect, make sense of (quite literally “turn into” meaningful, coherent events) and, sometimes, let go of (relinquish, abandon, renounce) in the face of ever more incoming (received) information, and which, in this technological age, may even be described as an onslaught (barrage, bombardment) of (useful?/useless?) information.

By using this stylistic device, Levy creates a scenario which, from the outset of the novel, confronts the reader with what information to absorb (what is essential and will be needed to make sense of events later in the novel) and what information to discard (the incidental). It is also this initial frenetic sorting (organisation, arrangement, taxonomy) of information that allows the reader to immediately experience the disquiet of the characters and, even though unlikeable, to feel empathy for their individual fates.

The first two characters we are introduced to are Kitty Finch and Joe Jacobs in what is presented as the aftermath of an adulterous encounter. They are driving back on a mountain road at midnight, Kitty driving distractedly and Joe asking, or rather pleading with Kitty to “please, please, please drive him safely home to his wife and daughter.” Joe Jacobs, we soon learn, is a poet, also known as J.H.J., or, for those closest to him, as Polish born émigré Jozef Nowogodzki. This character introduces, as a minor leitmotif, the loss, creation and recreation of identity, as well as the burden of history. Kitty Finch, on the other hand, is a mentally instable, anorexic botanist and a fanatical devotee of Joe’s who, through dubious means, locates him in France where he is on holiday with this wife, daughter and two family friends at a resort.

The first chapter, then, introduces and also alludes to the ending of the novel. The second chapter takes us back to the beginning, to the initiation (instigation) of events. It starts with the pool where Kitty Finch is found swimming naked and is observed by Joe, his wife Isabel, their fourteen-year old daughter Nina, and the family friends Mitchell and Laura. Kitty’s nudity is a recurring theme and, at a deeper level, could be interpreted as the exposing (revealing, divulging) of secrets, the stripping away of that which is presented and the uncovering of facts, illusions, fabrications and hidden agendas (clandestine or undisclosed desires, intentions, tactics, strategies and plans). Her superficially (seemingly) drowning figure is another recurrent motif and the title of the book, Swimming home, is in fact also the title of Kitty’s poem which she has written especially for Joe, in conversation with him, but also as a confession of her wish to drown herself. The poem and this motif in general hint at the psychological experience of drowning felt in particular ways by each of the characters in the novel.

Due to an error in accommodation arrangements, Isabel, Joe’s war correspondent wife, inexplicably and disturbingly invites Kitty to stay with them, even though it is obvious to everyone that Joe is nothing less than Kitty’s personal object-cathexis. Laura, the family friend, seems most perturbed by this decision and although she at first glance appears the most reasonable (sane) of the party, it later becomes apparent that Mitchell, her husband, with whom she owns a London shop dealing in “expensive African jewellery” and “primitive Persian, Turkish and Hindu weapons”, is a trigger-happy profligate and that their imminent financial ruin is, in a manner of speaking, drowning her.

Mitchell, the most unpleasant of the characters, introduces an ancient Persian gun, which, as Anton Chekhov famously said, once presented in the narrative must, eventually, go off. Mitchell’s obsession with ancient weaponry could be read as commentary on the violence suffered in our societies – physically, mentally, emotionally and structurally. The idea of violence is also echoed through Isabel’s work as a war correspondent and Kitty’s earlier confinement in a mental institution.

More subtly though, we see the unnoticed (unseen, disregarded, ignored) violent effects of absent parents on the budding pubescent Nina, who has had to deal with a mother who was both physically and emotionally absent and unavailable, as well as a father who was emotionally inattentive, but needed her to fulfil certain roles traditionally carried out by women, or at least by one’s partner. Consequently, even though there was no sexual requirement from her father, Nina still has to deal with the trauma of taking on the role of wife by supporting her father in other ways. This conflicting taboo within Nina, associated with an overly invested love for the father as a secretly desired lover, could be said to materialise (concretise) in the experience of her first period – in itself a violent and bloody act of the body – which then, in keeping with her life experience, is not shared with her parents, but with the intruder (outsider, stranger), Kitty, from whom she finds unexpected comfort, understanding, solidarity and companionship, even if fleeting.

The novel, shortlisted for the Booker Prize, ends as it begins: with a pool and a mountain road, with madness, despair and a confrontation with mortality. But don’t be fooled for a second; the plot is not made up only of what is written and what is read, but rather of what takes place in the liminal spaces, between words, lines, meanings and the constructions (misconstructions) each character and reader is bound to make.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project