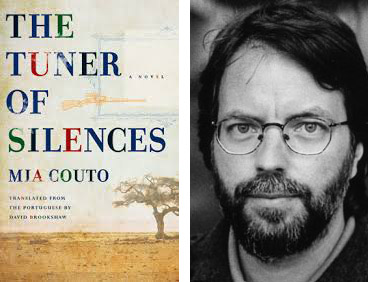

The Tuner of Silences by Mia Couto (Trans. David Brookshaw), Biblioasis, 2012. (Originally published in Portuguese as Jesusalém, 2009).

The epigraph of The Tuner of Silences is taken from Herman Hesse's Journey to the East: “The entire history of the world is nothing more than a book of images that reflect the blindest and most violent of human desires: the desire to forget”. Mia Couto's latest novel is filled with yearnings for a forgotten or lost past which are counterpoised with the violence implicit in the desire to erase. This is a novel interested in what it means to forget, as well as how memories are excavated, re-imagined and archived, traced on bodies and written down. Furthermore, it queries whether there might be an alternative to Hesse’s “book of images”, one capable of containing these disparate, sometimes conflicting, potentially untrue, recollections, and if so, who might author such a book.

From its arresting first sentence (“I was eleven years old when I saw a woman for the first time, and I was seized by such sudden surprise that I burst into tears”), the reader is introduced to the unexpected world of Jezoosalem – the name a crude parody and degradation of any promised land. An apparently disillusioned, putatively mad patriarch, Silvestre Vitalício, has withdrawn to this “wasteland” (11) with his two sons, a soldier, and an unfortunate, violated donkey “Jezebel”, whose fate it is to “satisfy the sexual needs of my old father” (12). The titular “tuner” is the youngest son and narrator, Mwanito, who has spent eight years in this abandoned game reserve. He has no memory of his mother who died when he was three, or the city they abandoned shortly thereafter.

Mwanito has been told that “the world has ended” (11). The survivors “knew nothing of what it was like to yearn for the past or hope for the future, but they were alive” (12). The question of what it might mean to be alive in such a depleted world is one with which Mwanito grapples.

In Couto's celebrated first novel, Sleepwalking Land (1992/2006), a boy and an old man journey through war-torn Mozambique, sustained only by reading the notebooks of a dead man: “Their destination is the other side of nowhere, their arrival a non-departure, awaiting what lies ahead. They are fleeing the war, the war that has contaminated their whole country” (1). One might say that in Tuner, Jezoosalem is one possibility of what might be found at the end of the road – an escape from war, but in this case, also from life itself.

Ntunzi, the older son, recalls life in the city, and on occasion shares these stories with Mwanito. In fact, it was his father who inspired his love of stories, advising him: “If they threaten you with a beating, answer with a story” (48). But he bemoans their current dire circumstances: “What story was there to invent now? What story can be conceived without a tear, without song, without a book or a prayer?” (48).

In his oft-quoted foreword to Voices Made Night, Couto writes:

Faced by an absence of everything, men abstain from dreams, depriving themselves of the desire to be others. There exists in nothingness that illusion of plenitude which causes life to stop and voices to become night.

Couto's stories illuminate those voices and explore the disfiguring effects of poverty and deprivation on the imagination and intimacy. The difference is that the protagonists of Tuner are neither indigent, nor are they refugees from war. They do not lack for food or clothing, which Uncle Aproximado delivers and receives payment for: their deprivations are of a creative and emotional order. The imagination has been banished; dreams, stories and even memory have been forbidden. Emphasising the debilitating effect of such a prohibition, Kindzu, the author of the notebooks in Sleepwalking Land, says that when the war broke out, “at night we no longer dreamed. Dreams are the eyes of life and we were blind” (9). Thus, in writing his life story, Kindzu terms himself “a dreamer of memories, an inventor of truths” (Sleepwalking 108).

Silvestre's antipathy to dreams is common to other characters in the Couto universe: Little Miss No wishes to be “spared the trouble of dreaming” (Under the Frangipani, 44). However, neither succeeds in completely suppressing the murmurings of their nocturnal world.

Silvestre accords Mwanito the semi-mystical mantle of “tuner of silences” for his ability to quieten his guilty and tormented thoughts and to provide him with a “refuge, tucked away inside a perfect silence” (205). However, Mwanito must learn to pierce the silence, in order to discover what absence it masks and ultimately to attune silence to the harmony of words.

The catalyst for the family's flight to Jezoosalem is “Dona Dordalma, our absent mother who was the cause of such strange behaviour. Instead of fading away into the distant past, she invaded the fissures of silence within night's recesses. And there was no way of putting the ghost to rest” (29).

Zachary Kalash, the mysterious soldier, also wishes “not to hear his own ghosts” (73). Yet, he is haunted by the memory of a wounded comrade: “every time he coughed, a torrent of bullets came out of his mouth. That cough was contagious: he needed to get away … He wanted to emigrate from the time of all wars” (79). Nonetheless, such an escape proves impossible, and Zachary comes to accept that “no war ever ends” (83). His body, marked by four bullet holes, is an archive of these wars. He is able to extract the bullets from his body, “pick them up one by one … and revea[l] the calibre of each and the circumstances in which he had been shot” (71), except for the fourth one from a more personal 'war', revealed by the novel's close. In this sense, Zachary embodies the trauma of war, reminders of which are ever present, even in Jezoosalem.

Mwanito learns to read, illicitly, from the labels of abandoned ammunition boxes. He learns to write, first in the sand (echoing Sleepwalking Land) and then on a pack of cards his brother gives him. These cards become Mwanito's first book. Only once he has learnt to read, can he learn to dream and to trust his dreams. In this sense, the novel is a particularly Couto-esque bildungsroman relating the coming of age of a writer. The scene in which Mwanito discovers literacy is particularly beautiful: “… instead of reading, I had a tendency to intone, as if I were in front of a musical score. I didn't read, but sang, thus magnifying my disobedience” (37). While writing, he “felt the world being reborn”; writing “was a bridge between past and future times, times that had never existed in me.... The more I deciphered the words, the more my mother in my dreams, gained physical and vocal expression” (38).

For Couto writers and poets “are all the impossible translators of dreams”. Reading his novels means submitting oneself to a logic where dreams are as real as waking life – a tricky logic to weave into the texture of a novel. (See for example the contributions from various writers to a recent New York Review of Books Blog about dreams in/and fiction,).

This incorporation of dreams into the waking life of his fiction is but one of the reasons Couto's work has most often been considered as “magical realism” – a term which forestalls, rather than illuminates one's reading. It is a label which seems all too easily applied to literature from the global south which does not quite fit into existing genres, or muddies “realism”. Franco Moretti suggests that the phrase itself has a troubled etymology and arose from a mistranslation of Alejo Carpentier’s writing: “Lo real maravilloso – not magical realism as it has unfortunately been translated, but marvellous reality. Not a poetics – a state of affairs” (Modern Epic, 233–234).

In Couto's fictional world, this “state of affairs” is one that takes seriously dreams, alternative beliefs, traditions, languages and philosophies – none of which are presumed static. Couto explains that in his work he wishes to: “storm one last bastion of racism, which is the arrogance of assuming that there is only one system of knowledge, and of being unable to accept philosophies originating in impoverished nations”.

For example, in his short story, “The Day Mabata-bata Exploded” in Voices Made Night, an ox steps on a landmine: “the ox pulverised, like an echo of silence, a shadow of nothingness” (17). Azarias, the shepherd, believes “the ndlati, the bird of lightning” is responsible, while the soldiers inform his uncle that the ox was killed by a landmine. At the story's conclusion, Azarias sacrifices himself to what he presumes to be the bird's vengeful flame, whereas he too has stepped on a mine – and yet both explanations coexist and can be considered true. Affirming this, in Last Flight of the Flamingo, we are told “the only facts are the supernatural ones” (1). The reader should be willing to immerse herself in Couto's fictional world, and experience the uneasiness or even delight which might accompany this immersion (feelings which are quelled by dismissing these moments as a magical realism) so that more of the intangible, often unpalatable truth of the waking world might be encountered.

Nonetheless, The Tuner is a noted divergence from Couto's previous work in that even the more “marvellous” elements have been muted, mirroring their erasure from Jezoosalem. The language, however, is as always peppered with Couto’s trademark aphorisms and inventive similes.

Life changes irreparably, with the arrival of Marta, who appears as an apparition, an “emissary” (123) perhaps conjured by Zachary, who claims to be “building a girl” (82), or by the men's desire for a lover or a mother. The chapters written with Marta as the focaliser also serve to parody and complicate gendered stereotypes as well as those held of Africa – in phrases which themselves, at times, verge on clichés. Marta’s presence begins the undoing of Silvestre's plan and the return to the city.

The insertion of a feminist critique of Silvestre's patriarchal, chauvinistic enclave is a key achievement of this text. So too is the creation of Silvestre himself, a complex, puzzling figure whom Couto never reduces to caricature. He is neither tyrant nor buffoon and reckoning with his guilt and his power remains one of the challenges facing the reader.

The act of recovering Dona Dordalma's voice is Mwanito's central occupation, although when her story is told, it is harrowing. There are no magical flourishes to accompany the telling of the events which led to her death. The societal silence which historically greets endemic violence against women is shattered, perhaps on one level all too literally in the novel, in the form of slogans shouted at a protest march.

Upon returning to the city, Mwanito, finds solace in writing even as he fears that he too is suffering from his father's blindness: “My blindness lifts only when I write” (229). In an interesting re-reading of “the sickness of the century”, Mwanito presumes this disease must be “some sort of calcification of the past, an intermittent fever made of time” (213). Thus Mwanito writes a book about Jezoosalem, in an attempt to cure himself and illuminate the many absences in his world.

Mwanito ultimately realises that he is not the tuner of silence, but of words. As Marta admonishes in her farewell letter to him: “No one can ask you to be only keeper of silences” (208). Mwanito must find a way to speak that is different from the soldiers who can only cough bullets or point to their scars as evidence of their forgotten or occluded history.

It is tempting to make a tenuous link with the narrator of Hesse's novel, who was on a “journey in search of Truth” (Journey to the East 37), shortly after the devastation of the first world war and attempts to write the book of his experience, a book of fragments which reconstitute themselves, of a “reality I once experienced” which “exists no longer” (67).

This faith in the written word is a mainstay of Couto's oeuvre. His novels illustrate the importance of stories for navigating life, for believing in something, in some other sphere where dreams are taken seriously, where life is not empty, or reduced to the dull echoing, meaninglessness of political and bureaucratic jargon. Couto has been awarded the prestigious Camões Prize for Literature for 2013 in recognition of his body of work. He has also been shortlisted for the acclaimed Neustadt Prize for 2014.

I feel envious of those who have never read Couto, who have yet to be enchanted by his words. Those who have, might find The Tuner a lesser achievement than his magnum opus, Sleepwalking Land. Nonetheless, this new novel remains a remarkable text. Its characters haunt my memory. I would press the book on readers, and then urge them to hunt out Couto’s back catalogue – whether to discover it for the first time, or to re-read with new eyes.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project