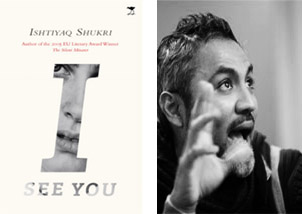

I See You by Ishtiyaq Shukri, Jacana Press, 2014.

I See You is explosive in its narrative undertaking as Shukri blows open a private drama to expose how its shrapnel lands on all quarters of the globe. The central narrative grapples with the abduction of Tariq Hassan, a prominent photojournalist. After no apparent action is taken to find him, his wife, Dr. Leila Mashal, decides to enter the political arena and runs for local elections. During her first public speech, she notes “that powerful clandestine and democratically unaccountable forces were involved” (24) in her husband’s abduction, leading to the further realisation that “while South Africans hold the vote, they don’t hold the power” (24).

Through the plight of his protagonists, Shukri highlights how power has become increasingly diffuse and insidious in our current political context. Leila’s disillusionment is far-reaching, striking a chord with political evaluations of South Africa’s democracy as ‘stillborn’. Like many contemporary South African novelists, Shukri interrogates the ‘new’ South African dispensation by exploring its temporal disappointments. For example, when Tariq attends an Opera performance, he prizes its narrative sequence precisely because it illustrates that “beginnings are for fools. By the time the new thing, the fresh start, the clean slate, whatever it is touted as, by the time it’s put to you, it is already an old done deal from which you and I have been excluded, but for which, sooner or later, we will end up paying the price” (120).

Tariq's acerbic observations seemingly resonate with his wife’s understanding that although power has changed hands in South Africa, is has not been adequately redistributed. And so there is the dismal pronouncement that “we’ve been had. Forget about beginnings. All we have is messy middles confused as twisted guts and eternal as the long intestine” (128). To this end, however, Shukri takes us further towards questioning the existential implications of deviating from a progressive temporal scheme. When we encounter Tariq in his cell, he attests to losing track of time. His thoughts are caught in a “loop” but “sometimes in the midst of repetition, a new thought flickers” (144). Yet in the desperate awareness of wanting to nurture this ‘fresh’ idea, he cannot let go of the infinitesimal hope of a progressive scheme; “how does one develop thoughts when they can’t be arranged into a reliable sequence? How do I determine progression?” (145). Overall, the temporal modality of the “twisted guts” (128) thus serves to mark incomprehension, irrationality and chaos – all of which can be reflected back to Leila Mashal’s decision to enter politics, as she too hopes that it can be restored to a more logical order.

Moreover, the structural overlay of the time of “no beginnings, just reinvented middles running on the loop” (128), is, in a moment of heightened intertextuality, noted by Tariq when he attends an opera performance, but it is also the general form of the novel that Shukri has himself written. Formally, the time of the “twisted guts” serves also to represent trauma: the narrative constantly returns to the scene of Tariq’s abduction. Tellingly, Leila did not ‘see’ this event and she can only think around its edges, which multiplies its traumatic impact – she is unable to confront it squarely and then let it dissolve. As we move back and forward in time, often looping back to the scene of Tariq’s abduction, we are also introduced to a host of narrative forms like reportage, interviews, emails, an opera score and instances of travel writing. As a result, the story coalesces as the reader locates points of interconnection between these fragments. In this regard, I See You can be considered fiercely contemporary as it acknowledges that technology has changed the way in which we consume and process texts and ideas. Ostensibly, the novel trusts our ability to switch between various forms at a rapid pace and, apart from the book's brevity (a mere 200 pages), it mirrors the speediness of global media.

Yet in making us aware of the length and breadth of our technological engagements, I See You also illumines the irony involved in seeing and being seen. The Jacket Cover is an image of a person peeping out through the ‘keyholed’ letter ‘I’ of the novel’s title. And as we peer into the private email exchanges between characters we become complicit in the panopticon-like surveillance of modern technology. Arguably, Shukri wishes to take us further than a ‘paranoid’ reading of global media as the bitter irony of our times, where, despite being bombarded by media, humanity is drawn into the web of diffuse power that surreptitiously turns a blind eye to what it has no interest in seeing. The novel highlights this despair through the lens of Tariq, a photojournalist, who travels to Palestine, Libya, Afghanistan and Kasalia (a fictional African country) and is punished for his various acts of seeing. Touching on his professional philosophy, Tariq understands that “people know when their souls have been seen’ (181) and the presumed loss of his life helps us to reflect on a human race that is quickly losing its ability see and to keep looking. Overall, as the novel draws to a close and Leila affirms her decision to enter politics in order to not lose sight of her abducted husband, we begin to understand that seeing is, in fact, the closest we can come to love.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project