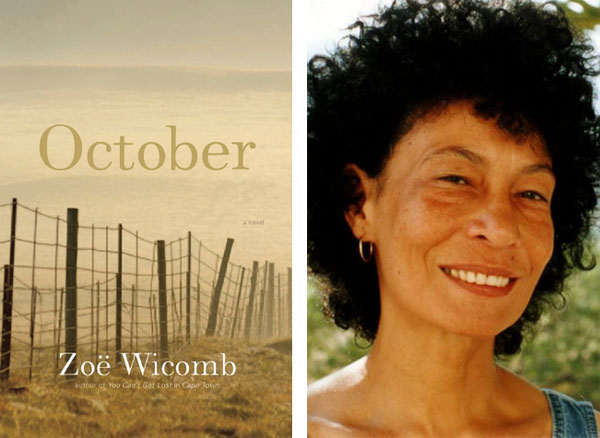

October by Zoë Wicomb, Umuzi, 2014.

Zoë Wicomb’s new novel commences with “a woman of fifty-two years who has been left”; a woman grappling with the gut-wrenching pull of emptiness and the memory games of nostalgia. And so, in this banal moment of despair, we meet Mercia. Mercia Murray, of the Murrays of Kliprand, Namaqualand. Now residing in Glasgow, Scotland. Mercia who prefers her three-syllabled name above the two-syllabled name of her youth, Mercy. Mercia who made it, who escaped the wretched life a Mercy might have had to endure but, who despite her accolades, finds herself alone, left, dumped, searching for ‘home’ in the same way a woman of any other name might. And it is during this time of doubt and desolation that Mercia – no Mercy – is called upon to witness: the demise of her alcoholic brother Jake; the lost youth and unseen grace of her “loslit” sister-in-law Sylvie; and the lot of the child, Nicky. Like Nicholas. Meester. “Pa, she corrects herself.” Pa, who taught her that “living amongst the Namaquas did not make Namaquas of the Murrays.” Pa, with his hand of anger and his cloak of shame, who “sinned … whilst his God turned a blind eye.” Like Mercia did, for so many years. But now, now that it is October, now is the time that Mercia will have to return home to bear witness. But it is not home she is returning to. It’s Kliprand. The place of long ago. And it is not her brother’s illness she will witness – not only – but the secrets of a family that once were hers and who now call upon her to claim them as her own.

Confronted by the skewed images of nostalgia and memory, and weaving through the tale threads of October and home, Zoë Wicomb beautifully narrates a story which may be construed, at least in part, as fictionalised autobiography. Because Wicomb, like Mercia, is an academic, living in Glasgow (where she currently is Emeritus Professor at the University of Srathclyde). And, like Mercia, she is from Namaqualand – the home of her youth and the lost home of her adulthood; facts which perhaps allow for the painful reality checks with which the fiction quivers.

As in her previous novels, Wicomb again explores racial and feminine identity, paying particular attention to the different roles women have to assume, fight for, and resist. Pitted against the roles of Jake and Meester (Pa), Wicomb contrasts the woman Mercia with “the girl”, Sylvie. In raw depiction the reader is introduced to Sylvie: sturdy “but not yet plump, with her strong legs and high Namaqua behind”, who stands by Jake – suffers “the attentions of a drunk, dysfunctional husband” – not so much because she wants to but because, as Mercia recognises, girls like her don’t get to escape. Girls like Sylvie have to make do with what they have and get on with it. There can be no contemplation of her circumstance, no ordering of her reality. There can be only fighting, or surrender, or acceptance – even of the wrongs which have been done to her. And it is especially through Sylvie’s silent acceptance that Mercia (and the reader) comes to behold the beauty and strength of this girl-woman, but also comes face to face with the reality of abuse so many women (of colour) have had to live with and continue to do so.

Wicomb’s portrayal of these many, often conflicting, roles women have to reconcile seamlessly in their thoughts is vivid and poignant, maddening and at the same time completely – intimately – known. But what was for me equally remarkable in reading this novel is that Wicomb does not assuage the burden men assume to emphasise that of women. Rather, she pushes against the edges of representation and time after time wrests from each character poses, thoughts, actions – a gesture, a pause, a glance, a word, a half-thought sentence – which compels surprising, even clashing, emotions in the reader so that like Mercia, the reader simultaneously resists and embraces any notions of family, loyalty and home. Because where is home? Who is home? Does Mercia leave home or is home taken from her when her long-time partner, Craig, leaves her for another woman? And is home really so ethereal that it can be left or taken away at a whim, or is it solid, like a rock? And is it home that makes us what we are? That carves out our identity long before we know how those two words (home, identity) will chaff against each other in life; moulding, tearing, shaping, breaking.

And if the first question of identity is home, the second might be language. Then class. Of these Mercia are not free and upon returning to South Africa, she finds that her “Afrikaans is rusty; her ability to make small talk rudimentary.” And, in her dealings with Sylvie, she finds that everything “is uncomfortable, creaking with embarrassment. A problem of class.” Yet Mercia also understands that rural coloured life in past and contemporary South Africa is complex, and tied to her more closely than she would have at first because it is, of course, a cage she has freed herself from. A cage which now beckons to be re-entered because there is the question of the secret, and the question of the child. But above all, there is the question of what Mercia will be able to live with and what not; how she will come to face herself. And it is here that Wicomb critically engages with the double identity of Mercia/Mercy who, “despite Jake, and Sylvie’s horrible chatter” knows “that this is home.”

October is a novel that swept me away from the first page. It is one which deals with Apartheid and post-Apartheid South Africa, but which avoids the pitfalls so many of these kinds of novels don’t. In a way it is a small story – the story of a life. Not a grand life, not the worst life. Just a life. Of a woman. Of colour. Who escapes but finds – as one so often does – that the cage she left was simply for a slightly bigger one. But this is not the time for musings such as these; these are musings that belong to October.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project