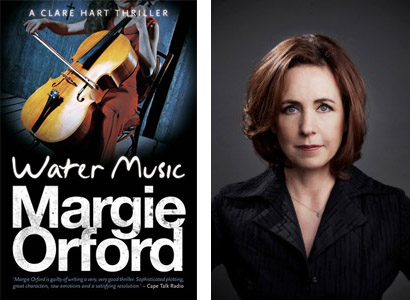

Water Music by Margie Orford, Jonathan Ball, 2013.

As a Fulbright scholar, award-winning journalist and film-director (interestingly also author of children’s fiction, non-fiction and school textbooks), she has an aptitude for near-forensic investigations into a variety of socio-political concerns that hit close to home. Simply put, she gives genre writing swagger, she makes it look good.

Before I set out to discuss the many merits of Orford’s latest work, it is worth reiterating how each preceding Clare Hart thriller focused on a specific current of violence past or present ripping through the rough-hewn fabric of our highly stratified, interstitial society: Like Clockwork with serial killings, sexual violence and human trafficking; Daddy’s Girl with the workings of the Numbers gangs; and Gallows Hill with the slave history at the Cape and extra-juridical killings during the heyday of apartheid. Orford’s sophomore effort, Blood Rose, was set mostly in Namibia, and took account of the killing of streetchildren amid shady military dealings.

With Water Music – Orford’s fifth crime fiction novel – the by now familiar corrupt politicians, ghoulish gangsters, struggling police force and relentlessly miserable batterings of wind that readers have come to expect are all in attendance, but never threaten to take centre stage. The novel opens on a bridle path on a freezing Cape mountainside with the discovery (by Cassie, a young girl busy horse-riding) of an emaciated, starved child of perhaps three years old. Buried, bound, wrapped in black plastic, it is a girl, so pale as to be translucent, with a widow’s peak and a tattoo roughly inscribed on her neck. Without revealing too much of subsequent plot developments, the young girl’s name is Esther and she will not be the only child suffering at the hands of an abusive patriarchal figure.

This is a case tailor-made for the unique skill-set of profiler, filmmaker and journalist Clare Hart (always drawing inevitable implicit comparisons to her creator), now in charge of the soon-to-be-scrapped fictional Section 28, concerned with the wellbeing of children and the protection of their Constitutional Rights. It goes without saying that Orford has a lot of fun with the ironies of the section's title, as it conjures up immediate reference to one of the most notorious Numbers gangs, a point made by a journalist at a press conference in the novel.

Clare’s services are called upon by an elderly man from the West Coast looking for help in locating his missing granddaughter, the gifted cellist Rosa, also a bit of a loner. Rosa has mysteriously cut ties with the music school offering her a scholarship, run by the unctuous director Irina Petrova. Under the patina of decorum and professionalism, further vulgar displays of power awaits. Two missing girls, two mysteries to solve, and time is ticking away.

While this sparse description gives away little in terms of plot development, Orford’s devoted fan-base may rest assured that these twin mysteries combine to produce the firmest of foundations for Orford’s larger inquiries into the vestiges of violence that she argues seeped into the bloodstream of the body politic after the erosion of apartheid.

This time it is the hornet’s nest of religious fundamentalism and its most insidious implication in patriarchy that come under the microscope. Few readers will be able to anticipate the full weight of Orford’s tremendous skill in weaving together the stories of the two vulnerable women (girl and young adult) into a hold-your-breath final third act, and few will remain unmoved by the vicious cruelty these two female figures – among others – must endure. After the vintage (of) villainy of the likes of gangsters Graveyard de Wet and Voëltjie Ahrend, the character of Stern truly makes one’s skin crawl.

In terms of its writing aesthetic, Water Music continues the direction taken in Gallows Hill, in itself a work that brought into relief the crime novel’s ability to offer more than cheap thrills and predictable social analyses: rather than the sledgehammer brutality that creeped into all three of Orford’s first three novels, what we encounter here is a further increase in subtlety and sensitivity. Orford has never written more compassionately, more cohesively or convincingly on the topic of violence.

There is literally not a chapter that passes without many a passage that capture the imagination. Consider the following, if you will, from the novel’s fifth chapter, representative of the novel’s tempered style:

Clare knelt beside the fallen oak, reading the tiny marks and disturbances to the soil in a way that another woman might read a book. There wasn’t much – just a flattening of the leaves, a frightened animal seeking refuge from the storm, perhaps. Clare looked up at the thick undergrowth that ringed the clearing. The bridle path was a narrow opening in the reeds; beyond, on the other side of the river, a forest where shadows shifted the shapes of the trees (22).

The fact that characters carry over from one book to the next in this series allows for an ever-deepening emotional investment from the reader into every subsequent narrative. The reverse is then also the case – that the writer must reward such investment with greater depth and complexity in each episode.

Orford is certainly a canny writer, and what she offers here, on top of the gripping central mysteries, is her most expansive chronicle of the relationship between Clare and Riedwaan Faizel of the Police’s elite Gang Unit. Apart from being an effective formal device to create and maintain a level of suspense and tension in the narrative, Orford alternates between a focus on the twin cases the pair are working on and an intimate view of their own demons and difficult relationship.

Clare’s fear of commitment and her constricted relationship with her twin Constance are well-established parts of her character, yet Water Music places her in vastly unfamiliar personal territory: she is pregnant with Riedwaan’s child, and must come to terms with the fact that she is now responsible for a life more than her own, less in control and more emotional than she is accustomed to being. In turn, Riedwaan has to deal with his pending divorce, the fact that his estranged wife now lives in Canada with their daughter (traumatised after her kidnapping in Daddy’s Girl), his deployment to the Northwest Province after already being stationed in Johannesburg (straining his relationship with Clare even further), and the rapidly declining health of his mother. Childhood memories and previous traumas also come back to haunt him this time around.

Riedwaan is not the only character haunted by spectres from his past: in fact, Water Music makes repeated mention of ghosts, spectres, death, loss and mourning. Although Orford manages to deftly sidestep the melodramatic and unnecessary histrionics, there is plenty on offer here that is truly grotesque and disturbing, not least the sections that deal with the ghastly ramifications of patriarchal ideology.

Apart from the chilling interactions between many of the characters, Orford’s storytelling has a strong hand in the Gothic, and features a castle with a mysterious foreign owner; tunnels beneath the city; secret locations; an ominous mountain “retreat” called Paradys (Paradise); references to Bach and Mozart and characters that are classically trained musicians; as well as an icy Cape winter setting with mist, rain and fog. Of course, Clare’s investigations place her own life and that of her baby in danger. The novel’s beautifully weighted descriptions of Hout Bay and its surrounds certainly create a vivid atmosphere, while the Cape Flats are rendered with the writer’s typical sobriety and texture.

Water Music is, consequently, a moving and emotive novel constructed around human entanglements, shaped by the predicaments that none of us can escape from. The writing, a product of this time, and resolutely of this place (yet appealing to a transnational readership), is exemplary of how the form in question can be artistic, accommodating a rich variety of concerns and voices without seeming contrived. South African crime fiction in the guise of Orford’s writing is elevated to a plane that once again rubbishes the binary between high and low forms of culture and writing.

Every detail in Water Music convinces. Every sentence is clipped, pared down, muscular, every emotion captured with poise and precision. It is thus no exaggeration to claim that Water Music is Orford’s best work yet. It makes of the crime novel a space of symphony and harmony rather than a necessarily discordant symbolic space. This is a space where the whole is infinitely richer than the sum of its parts, and the confidence in composition welds an undercurrent of vibrant intellectual life to the socially-conscious writer’s on-going diagnostic project.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project