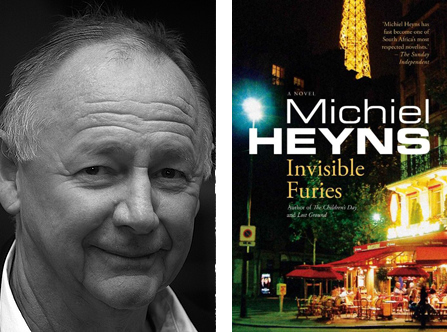

Invisible Furies by Michiel Heyns, Jonathan Ball, Johannesburg & Cape Town, 2012.

A new Michiel Heyns novel is always a cause for celebration, and this, Heyns’s sixth novel in ten years, surely makes him of one South Africa's most prolific literary talents. Invisible Furies was released only months prior to the announcement that Heyns had won the 2012 Sunday Times Fiction Award for Lost Ground. (He shared the award with Marlene van Niekerk in 2007 for his accomplished translation of her novel, Agaat.) No doubt the publicity machine will ensure a knock-on effect and spike in sales for this very different novel – a fact which is not at all displeasing.

Heyns is uniquely talented in that his novels alternate between a South African and European locale and operate along a wide spectrum of different genres seemingly with ease. Invisible Furies is set in Paris, worlds away from the dusty fictional Karoo town of Alfredville, where his unconventional “crime novel” Lost Ground is set. If the backdrop to that novel “is not a landscape that conforms readily to a formula: it refuses to be reduced to cliché or even a meaning” (62), it is difficult to imagine a more mythologised and readily fictionalised city than Paris – the name alone conjures up an exhausting list of clichés in the global imaginary.

The challenge for any author in revisiting Paris, then, is to present it afresh to a readership without resorting to a “formula”. This challenge to rewrite a familiar trope is amplified by the fact that the novel is inspired by Henry James's The Ambassadors (1903) or, as Heyns words it in the acknowledgements section of the novel, “substantially recas[t] and reinterpre[t] the Jamesian given” (296).

While some readers of this novel may be familiar with the plot of The Ambassadors, I think it is fair to say that many will not, and so the problem facing the reviewer is what weight to accord the “Jamesian given”. While the novel is obviously a Jamesian pastiche, it is not just that. I have approached the text with its inspiration in mind, identifying affinities but also considering the novel in its own right, as it deserves. In fact, it seems the “Jamesian given” ultimately proves constraining for Heyns's prodigious imagination, as the plot at times strains against the strictures to which it must adhere.

The most striking liberty that Heyns has taken with James's cast of characters is with the nature of his protagonist's loyalties. In The Ambassadors Lambert Strether is sent to Paris as an emissary of his fiancée, Mrs Newsome. He has been commissioned to recall her errant son to the mysterious family business in provincial Woollett, Massachusetts. In Invisible Furies, freelance editor Christopher Turner has been tasked by his childhood friend, and the object of one of his heart's “invisible furies”, Daniel de Villiers, to return the heir apparent, Eric de Villiers, to 'Beau Regard' (the humorously anglicised and ungrammatical version of the French for “beautiful look”) – a farm outside the town of Franschhoek, which is not immune to aspirations of faux-European grandeur.

If one is asking whither the plaasroman in contemporary South Africa literature, here we are presented with its possible “sequel”: where Van Niekerk's Jakkie, in Agaat, escapes to Canada to become an ethno-musicologist, Eric becomes a claquer in Paris: he is “employed to look beautiful and applaud vigorously” at fashion shows. (52).

With the emphasis on the fluidity of sexual attractions and the gay quartier of the Marais as epicentre exerting its magnetic pull on the events, Heyns has liberated James's mannered characters from their closet and, in his reappropriation, explicitly queers the Jamesian given (the implicit “queer” narrative in James's fiction has been the subject of much critical analysis – see for example Eve Kosofky Sedgwick's reading of “The Beast in the Closet” in The Epistemology of the Closet and the responses to it). Heyns's novel is set in a Paris, where as the actor Simon Cleaver sardonically observes, “bed no longer comes with breakfast” (98), and yet “nothing in Paris comes without a bed” (99).

Christopher has not returned to Paris since his trip with Daniel thirty years ago. His happiest memory of their time together, in fact his one memory of unadulterated joy, is a night of drunken revelry, where in a scene reminiscent of Truffaut's Jules et Jim, they ran along the Seine “laughing and singing, ‘I can't give you anything but love, baby’” (23). But like that classic film, three is an unwieldy number, and Christopher's affections are soon usurped by the arrival in Paris of Daniel's lover and future wife Marie-Louise, and so his remaining time in Paris was akin to “a season in hell” (24).

Since then, Christopher feels “nothing had happened to him” (121). The narrator observes drolly that Christopher's career as a teacher was “ultimately, taxing only in the toll it took of his youth, his enthusiasm, his love of his subject, his belief in the value of literature” (121). As an aside, there is of course the in-joke that Christopher, as a student and teacher of literature, is oblivious to finding himself a pawn in the plot of a James novel.

Our protagonist seems impervious to the charms of the fabled “city of lights”: “One gets irritated with the implication that one should fall flat on one's face in worship each time one turns a corner in Paris” (12) and equally baffled by the world of fashion: “[T]that merely covering the human body could be such a multifarious business” (122). However, Christopher gradually falls under the spell of the seductive Eric de Villiers and his older paramour, Beatrice du Plessis – an ex-supermodel who hails from Potchefstroom, a fact “which did not open up many avenues of conversation” (115).

His erstwhile love of order (135) is challenged in the course of his conversations with his Parisian interlocutors: “It's just that it's become so difficult to tell [the moral order] from all sorts of other orders of things.... The aesthetic order of things.... but also the pragmatic order of things, the politic order of things, the expedient order – and even just the merciful order of things” (223) and the validity of his mission is muddied.

While Henry James is concerned with the interactions of America and Europe, it is the pathways between South Africa and France that are in focus here, and are responsible for some of the wittier interludes in the novel. As Martha confides to Christopher: “The French, as you may know, think they are mad about Africa, which to them means The Lion King with sex” (29). On another occasion, two Afrikaans tourists, unaware of Christopher's nationality, express their disappointment in loud Afrikaans: “Ag kak! … Nou't daai poephol ons tafel gegryp” (153). However, the migrations between the rest of the world and Paris are not merely fodder for amusing cultural anecdotes. The harsh reality of immigration and rising hostility to “outsiders” are variously alluded to.

Towards the beginning of the novel, we are told that Christopher has kept a copy of L'Étranger next to his bed, “retaining a nominal connection with la langue” (18). On one of his first walks in the city, Christopher encounters an extract from Walt Whitman: “Étranger qui passe, tu ne sais pas avec quel désir ardent je te regarde”(Passing stranger! you do not know / How longingly I look upon you) supposedly adorning the front of the iconic Shakespeare & Co bookshop. However, the actual frontispiece of the store displays the motto of the late owner, that other Whitman, George: “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise.”

This interesting erasure suggests the central tension in the world of the novel: the call to be hospitable to strangers has been superseded by desire and the desire to look at the other. It is in this authorial erasure that the otherwise apparently conflicting themes of beauty and Parisian “outsiders” in the novel coalesce.

As Fabrice darkly proclaims, “I have an eye. He is not from Paris, he doesn't inhabit his clothes as if he belongs in them, he doesn't walk the street as if he's at home in it. And most of the foreign boys are Romanian. Romania is very homophobic, so they can't ply their trade there” (279).

Eric confesses to Christopher that, upon arrival in Paris, he longed to possess “the code, the Open Sesame to that secret world behind the door” (180). For Eric, the key to accessing this world is beautiful clothes, and it is ultimately revealed that his way was smoothed by Fabrice who euphemistically calls himself “a social coordinator catering to a niche market” (280).

Maxime du Camp wrote of Paris in the late 19th century: “Fashion is the recherche – the always vain, often ridiculous, sometimes dangerous quest – for a superior ideal beauty.” It is these elements of vanity, ridicule and danger that Heyns attempts to capture and illustrate.

In fact the most nuanced meditations on the meaning of beauty stem not from engaging with clothes or fashion but from the encounter with more traditional forms of art – sculpture, photography and painting. A Picasso painting is “beautiful but terrible” (245). Eric's obsession with two photographs, of a “terrifying and beautiful” horse, rearing away from invisible danger, and of a young black man, “his back disfigured by a single weal, his shoulder hunched against the next lash of the whip” (184-5) reveals his own capacity for brutality. Eric admits: “They were grisly if you thought about them, about what was happening there, but just as objects they were very beautiful.” On another occasion, during a spontaneous trip to Florence, to “assist” Eric in retrieving Beatrice's daughter, Christopher reflects on the contrasting depictions of brutality in the different versions of David. (Amusingly enough, a miniature statue of David exists as a more concrete incarnation of violence, as the murder weapon, in Lost Ground.)

As these dark intimations suggest, the “charm” (273) that Christopher falls under is inevitably broken, as we know it must be, dictated by the denouement of The Ambassadors. Christopher himself, though, is slow to interpret these signs. Christopher's naïveté at times beggars belief, but any impatience the reader might feel is expressed in the person of Martha Samuelson, who acts as a necessary foil to him. Christopher's rapport with Martha, although often in the form of somewhat incongruous – and improbable in the contemporary setting – Jamesian dialogue is also one of the delights of the novel. Heyns's dexterity with language is given full freedom in their interactions:

“I get the impression,” Martha said, “from the relish with which you say that, that you don't really mind being embroiled in this little imbroglio”.

“Embroiled in an imbroglio. Do I strike you as so tautologically immersed?” (222).

There is real pathos in the moment when Christopher's delusions about Eric are finally crushed. Although inevitable, Heyns rescues this moment from potential caricature or bathos with a descriptive tour de force:

[A]ll beauty had been mired by the touch of Fabrice, all virtue made suspect by the dark confidences of the woman in black. The streets were just extensions of catwalks, the shops just purveyors of enhancements to the display of human flesh, the cafés just seating for phalanxes of claquers. (287)

Olga, the woman in black, has alerted Christopher to the subterranean aspects of Paris. “People talk about the Seine … about its bridges, how beautiful, how romantic, but for me … they will always smell of piss and shit” (260). And yet, in his despair, he flees the Marais and descends to the world below the bridges, where he encounters the city's denizens, engaged in their own performances. Two men embrace, mirroring his own encounter, sans Daniel's clowning and irony, listening to a woman singing one of Mahler's “Rückert lieder” (292). She is oblivious of an audience, does not need a claquer as her songpleads for love, not for beauty or youth's sake, but for “love's sake alone” (293). And in this moment, despite his anguish, Christopher “felt consoled, by the consolation that beauty brings, however tainted its sources and vile its ends” (295).

This ending recalls the melancholy end of Teju Cole's Open City (2011). Of Mahler's final works, Cole's protagonist declares, “[t]he overwhelming impression they give is of light: the light of a passionate hunger for life, the light of a sorrowful mind contemplating death's implacable approach” (250). One of the epigraphs to Heyns's novel, taken from The Ambassadors,includes the phrase “in the light of Paris one sees what things resemble”. Invisible Furies ends with the dimming light of Paris and what the light of Mahler reveals.

If the many themes in this novel seem uneasily reconciled, then the desire to thread them through a plot already constrained by the framework of The Ambassadors sometimes falters. However, Heyns's treasure chest of vocabulary and dialogue, into which he habitually dips, and the sheer beauty of his writing, especially in the set pieces – reflections on beauty and regret, of daily life in Paris, descriptions of lavish or grotesque parties – ensures that, despite minor hesitations, this book remains a stirring elegy on lost youth and beauty in all its manifestations.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project