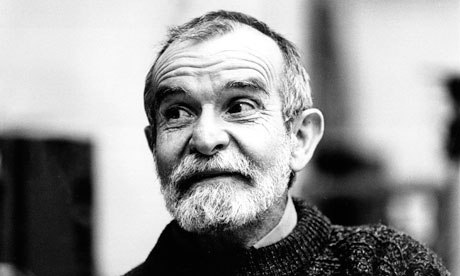

Over a month-long season from March into April 2014,Athol Fugard, the man Time magazine has described as the “greatest active play-wright in the English-speaking world,” performed a remarkable feat at New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre. Not only did he return to the boards at the age of eighty-one after an absence of fifteen years, but he pulled off the trick, night after night, of acting the part of a frail octogenarian as if he himself were thoroughly chipper – which he indeed appeared to be as he commanded the stage with exacting precision. In truth, though, Fugard the playwright-actor was every bit as vulnerable to mortality as the character he was playing with such zest, a grandfather called Oupa who does, in fact, fall down dead at the play’s climax.

Several years ago, Fugard underwent revascularisation grafts to aid his circulation. At the age of eighty-plus, with declining physical powers, there is no telling what might happen from one day to the next. Indeed, in an interview during rehearsals for The Shadow of the Hummingbird’s world-premiere run, Fugard said: “I really don’t know what comes after this. I’ve got five stents in my body. You know, I could be gone before the opening night! I don’t know how much time I’ve got.”

The two figures, Fugard, the aged thespian, and Oupa, the doughty grandfather of a beloved grandson, Boba, share too many similarities for the audience not to see them as versions of each other. Like Fugard, Oupa is given to writing daily journal entries about life, nature and people, and he is a bookishly homespun philosopher of sorts. And, as in Fugard’s case, his spirit appears to be indomitable, as if his continued thrusting through the tides of time is motored by sheer obstinacy. It is almost as though Fugard’s will to life is more convincing, by a long stretch, than Oupa’s acted death on stage.

Protean spirits such as this, in addition to visceral engagement with the challenges of human existence in hard geographies and difficult circumstances, have been the hallmark of Fugard’s long career. In the annals of South African letters, he has no equal in staying power, except perhaps for Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer. Many of Fugard’s contemporaries, both South African and global, have passed on: Harold Pinter, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, John Osborne, Guy Butler, Anthony Delius, South African poet-playwright (and close friend) Don Maclennan, Jack Cope, and a clutch of others. Fugard, by contrast, seems unwilling even to slow down. As the artistic director of the Long Wharf Theatre, Gordon Edelstein, notes in the program for Hummingbird, Fugard is currently working on two new plays and an extended work of prose fiction. The man is unstoppable. Or so it seems.

Still, Fugard’s “late style,” reminiscent in some ways of Philip Roth’s last half dozen books, shows a preoccupation with beginnings and endings, and with how best to complete the circle of life. If the end must come, Fugard’s Hummingbird seems to be suggesting, then let it come in ways that return us to the realms of discovery and play. Let the spirit of quizzical wonder, of hopefulness despite the odds, never relent. This determination to remain buoyant is Fugard, writ large. He has been acting on such an apparently uncomplicated impulse, a rebellion against the death drive, one might say, over his entire working career as a playwright, which now comprises a span of more than fifty years.

***

Identifying various examples of the “Fugardian” spirit – as manifested in the playwright and his characters’ special brand of back-against-the-wall pluck – is a useful way of charting the shape of Fugard’s extensive body of writing. It is worth considering, from the vantage of The Shadow of the Hummingbird’s performance in New Haven, spring 2014, how different manifestations of rebellion against defeatism have shaped the playwright’s creations since 1958, when he first began to “work” the drama, one might say, of very pronounced, and regionally located, human predicaments.

One of the ways to understand the trajectory of Fugard’s work is to see it as a gradual development from a more to a less socio-politically specific domain, and from a less to a more personally reflective space, although both sides of this all-too-easy polarity are present in lesser and stronger shades, in asymmetrical combinations and sequences, throughout his career, making a mess of any overly schematic long-range view of his work. Nonetheless, it remains true that the post-apartheid period has seen Fugard exercise a greater sense of freedom to follow what one might describe as a whimsical, or philosophical and personal bent, than in the iron-barred apartheid years. This is certainly true of Hummingbird, which by Fu- gardian standards of length, intensity and dialogic freight is a mere whimsy of a play; it is, indeed, a wistful one-act meditation on the wonders of the human imagination, without confronting the dictatorial intolerance of the “real world.” Such speculative content, bodied forth in a grandfatherly dialogue between Oupa and his grandson Boba about Plato’s allegory of the cave in The Republic, would in the South African struggle years of littérature engagée have been met with raised eyebrows and even a measure of disapproval in some circles. Thankfully, times and contexts have changed.

New Haven in 2014 is anything but Johannesburg, Cape Town or Grahamstown in 1988, places and periods in which Fugard was occasionally under suspicion for being “bourgeois,” and insufficiently revolutionary. But such misgivings, understandable as they may have been in the light of contextual pressures, would have missed something very important, the golden thread, one might say, that connects Fugard’s more political plays with his less political works: the unquantifiable substance of spirit and the defiant pluck that shines through every Fugard production since the late 1950s, culminating in its forgivably airy and whimsical voicing in New Haven.

It is common cause that Fugard’s social conscience was sharpened in 1958 by a period of employment, while in his twenties, as a clerk in the Fordsburg Native Commissioner’s Court in Johannesburg. The tribunal was essentially aimed at pass-law enforcement, a place where black South Africans were prosecuted for failing to have the right endorsement (an official stamp) in their hated “passbooks,” allowing them (or not) to spend time, for purposes of employment, in areas designated under apartheid for white people only. “During my six months in that courtroom,” Fugard has written, “I saw more suffering than I could cope with. I began to understand how my country functions.”

Fugard duly went against the lynch-gang political current, befriending black people in Johannesburg’s famously cosmopolitan Sophiatown area – later razed to the ground by state bulldozers to make way for a white suburb called “Triomf” – and meeting the likes of actor Zakes Mokae and writers Lewis Nkosi and Bloke Modisane. The playwright, along with his wife Sheila Fugard, launched the African Theatre Workshop group, which saw the staging of Fugard’s first full-length play, No-Good Friday, alternately featuring Fugard himself and Lewis Nkosi in Johannesburg productions: Fugard acted the part of Father Higgins when the piece was staged at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre, and Nkosi acted the role when No-Good Friday played at the “white” Brooke Theatre, where a multiracial cast was deemed illegal.

Though both No-Good Friday and Fugard’s second play, Nongogo, are – by the dramatist’s later standards – a touch wordy and melodramatic, they feature black characters that refuse to lie down despite annihilating odds. Willie in No-Good Friday bravely declares: “There’s nothing that says we must surrender to what we don’t like. There’s no excuse like saying the world’s a big place and I’m just a small man. My world is as big as I am.” In Nongogo, Johnny tells the “shebeen queen” [speakeasy proprietor] Nongogo that the only time a person is really safe is “when you can tell the rest of the world to go to hell.”

That’s the Fugard spirit for you, and it has remained constant, in one form or another, for over half a century. It has outlasted apartheid, and it will go down laughing at the antics of “Zumocracy,” the current bout of public stealing and economic disenfranchisement riding high in an ever-gaudier “rainbow nation.”

Nongogo and No-Good Friday made their appearance in the late 1950s. Almost twenty years later, in the mid-1970s, materialist critics located at South Africa’s top three English-speaking universities would begin to find fault with Fugard for the “liberal” fallacy of seeking salvation in individual acts of rebellion rather than class action, but the strategy of downright refusal, of swimming upstream and damn the consequences, is arguably the bottom line in all forms of resistance. Symbolic forms of renitence, consciously staged and aesthetically mediated as acts of public persuasion – later to find the ungainly descriptor “conscientisation” – were cornerstones in the fight against apartheid, especially in mobilising international opinion against the South African police state. The only way for a minority to oppress a majority, as whites did for over forty years during apartheid, is to break people’s backs, to render abysmal conditions as “normal.” The single manner with which to combat such downgrading of human worthiness is to reassert an unyielding will to betterment. For this alone – quite apart from his many other achievements – Athol Fugard deserves a few streets named after him in South Africa, if not a national holiday.

The most significant counterweight to the dogged optimism in Fugard’s early characters was the playwright’s immersion in midcentury existentialism. By his own admission, Fugard was profoundly moved by the existentialist philosophers, Sartre and Camus in particular, and his second wave of plays, especially The Blood Knot, Hello and Goodbye, People are Living There, and perhaps his most famous single work of all, the classic, Godot-esque Boesman and Lena, all stage a protracted showdown, lutte à mort, between a sense of coruscating futility on the one hand, and a determination to dream, to hope, and to believe, on the other. Morris and Zachariah, the half-brothers in Blood Knot, square off against each other, and against a godless world, in the squalor of an apartheid tin-shack set in the industrial backwaters of Port Elizabeth in the early 1960s. For them, the one brother’s half-white “blood” (Morris) betrayed the other’s deeper blackness (Zachariah) in a race-obsessed country; more, they were born into a secular empire in which an empty modernity after Auschwitz rendered their (poignantly staged) condition universally recognisable, not only in Johannesburg, where Blood Knot premiered in 1961, but also in New York, where an off- Broadway production directed by Lucille Lortel launched Fugard’s American career.

From this point on, Fugard’s work – like that of major South African writers Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer, J.M. Coetzee, Breyten Breytenbach and Antjie Krog – found the seam of regional as well as universal significance. For all these writers, and especially Fugard, it was an interweaving of cultural, racial and socioeconomic conditions, a twisted “knot” whose painful torsions were felt in local predicaments and their derivation from a larger sickness, a moral destitution at the heart of twentieth-century Western civilisation.

In the “Port Elizabeth plays” featuring poor-white characters, Hello and Goodbye and People Are Living There, one destitute individual after another stumbles through an evacuated modernity, struggling with the futility of an existence in which self-interest on a massive, social scale finds a fitting home “in a province,” to borrow the title of a famous Laurens van der Post work. Fugard’s down-on-their-luck white chancers, however, were never going to find traction on the world’s big stage, given their relative economic and racial privilege, and it was only when the playwright hit upon the figures of Boesman and Lena, two “nonwhite” characters (in the racial parlance of the time) that the world at large came to see – and more fully appreciate – the special gifts of Athol Fugard.

Take, for example, the review in the New York Times after the play’s revival at the Manhattan Theater Club in 1992, in which Frank Rich found that Fugard’s “image of an itinerant homeless couple sheltered within their scrap-heap possessions and awaiting the next official eviction is now as common in New York City, among other

places, as it was in the South Africa where he set and wrote his play in the late 1960s.” Who would have imagined, Rich asked, “that the universality would soon prove so uncomfortably literal?” Although the New York of the early 1990s was a far rougher place than the Manhattan of today, following Giuliani’s “zero tolerance,” police-driven clean-up, it is fair to argue that Boesman and Lena found a near-perfect coalescence between the universal and the particular on a transnational scale, in a way that few other writers have managed. In the same way that noir films (such as Escape From New York, for example) found a turning point of rebellion in the gothic shadows of capitalist modernity, Boesman and Lena spoke for the plight of ordinary humanity in a world that appeared to have lost the balance between success and succor.

Boesman is a sinewy, tormented man who reprises the material and moral humiliations he has suffered at the hands of a heedless racial capitalism by mercilessly tormenting Lena, his luckless partner in life. As many critics have noted, at its core Boesman and Lena is a love story, a parable of Adam and Eve twisted almost beyond bearing by circumstance. In its many performances, and its two film versions, the piece, with searing feeling, spoke at once of both the symptom it dramatised and the condition from which the pathology arose. Whether one calls that condition neocolonialism, or apartheid, or capitalist modernity, in one way or another it implicated everyone who watched the play. Something was not right. For as long as it remains possible for people to be cast out as rubbish in the way that the characters Boesman and Lena are, and for as long as the world knows that these two individuals are by no means mere fictions, but suggestive of real suffering, on a day-to- day basis, who can continue to turn a blind eye? Yes, it was due to apartheid, a local sickness in a small corner of the world, but it was also due to the historical pillage that had made apartheid possible – the continuing co-implication of apartheid and capitalism – that transformed Boesman and Lena from local play-actors to Beckettian figures in the symbolic imaginary of the Western literary canon, as emblematic in their way as Vladimir and Estragon.

And yet, sitting around a makeshift fire in the middle of nowhere on the pitch-black mud-flats near Port Elizabeth, Lena sings her way through the small hours of the night. She has been run ragged by Boesman, rendered the object of ugly threats and cheap jibes; she has sacrificed her daily portion of Boesman’s bottle of wine in return for the company of the mute, dying man, Outa, and she will not be deterred. In his pioneering study, Southern African Literature: An Introduction, South African poet, playwright and Fugard contemporary Stephen Gray identified Lena as an avatar of the “Hottentot Eve,” an immemorial figure in the region’s literary canons. As such, she is a multivalent, potent trickster, and she is innately wise in a way that defies the western project in Africa or the depredations of the white man’s guns, trinkets, and magic potions. The Hottentot Eve drinks wine and laughs and sings with guttural abandon. There is, in her, the Bacchanalian flint of humanity itself, and her presence calls to order the systems and processes, people and politics, that (continue to) deny and degrade her. In cheapening her, they cheapen humanity, and they degrade themselves. In the guise of Lena, played magnificently by Yvonne Bryceland (opposite Fugard as Boesman) in the early productions of the play, and in the first movie version (directed by Ross Devenish, 1974), this African “Eve” is possibly Fugard’s most magnificent creation.

***

It is also true, however, that writing and acting the part of Boesman in 1969 in apartheid South Africa rendered Fugard a white author “talking black,” so to speak, or speaking on behalf of the Other (in postcolonial lingo), and this did not always sit well with the rising wave of black consciousness that began to emerge in the 1970s, its rage exacerbated by the death of Steven Biko in 1977 at the hands of the South African Police. Fugard, though, was well ahead of the game. Already in the 1960s he had begun working with a group of amateur performers called the Serpent Players in New Brighton, a black township near Port Elizabeth. According to Albert Wertheim, author of The Dramatic Art of Athol Fugard: From South Africa to the World (2000), this engagement allowed the playwright to reconnect with the pulse of life in the black areas from which he had largely been estranged by the physical and legal restrictions of apartheid.

At the time, Fugard was developing a version of “deep” or method acting in the guise of Grotowski (and before him, Stanislavski) – urging his actors to draw on their own inner resources, based on personal experience, when “acting.” It was a kind of anti-acting, a form of “getting real” on stage, especially when set against the version of drawing-room theater that was still predominant in neocolonial white South Africa, and it produced – in the plays Sizwe Banzi is Dead, The Island, and Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act, among others – an explosively unique South African version of play-making.

Sizwe Banzi and The Island must surely rate as among Fugard’s best plays, combining keen dramaturgical innovation with a form of shocking, or “raw” human revelation – a stripping away of reductive or inflated frames of reference, restrictive categorisations, and deceptive language games. The plays do this, “dramatically,” by means of personally invested enactments of experiential feeling whose “acting out” is all too real. Sizwe Banzi performs its theatrical work by cutting through various frames, or boxes, if you like, of self-staging – ways in which people act themselves out or are acted upon – in stories they tell themselves about themselves; in corny “happy snaps” (studio photographs or, today, selfies and facebook photo posts) by which they try to convince others that they are “successful”; via restrictive endorsements stamped into apartheid pass-books; in workfloor sociolects of master-slave (non)communication, among other such templates. The play then digs down beneath the acting out of one’s life, or the acting upon a human life from without, and searches for an expression of the human core not smothered within such representative enclosures, such real-life mimicry.

True to Grotowskian “poor theater,” the “fourth wall” is broken down in this process. In Sizwe Banzi, studio photographer Styles talks directly to the audience, drawing them into his punishing and witty play with verbal and pictorial frames, and rendering them vulnerable, or disarmed, in the process. With Fugard, one is often rendered more susceptible, more open to a kind of undoing, than one is accustomed to, losing that carapace of defensiveness by which we tend to keep the outside out. Similarly, in The Island, the audience is drawn into the spirit of play-acting (here, a prisoners’ performance of Sophocles’s Antigone) while also being affected by the exposed underbelly of such “acting” in the faux-actors’ “real” dramas, played out behind the scenes of the play-within-the-play. These two works achieve an intricacy of wit, feeling and depth from both the Fugardian creative direction and the communal authorship that arose as John Kani, Winston Ntshona and Fugard “workshopped” the plays into being rather than composing them beforehand. Kani and Ntshona are duly credited with co-authorship of these seminal works, plays that set the stage for a new generation of revolutionary “township” drama, in the South Africa of the 1970s and 1980s, such as the definitively South African pieces Woza Albert! and Sarafina! among others.

The jointly authored “township plays,” as Dennis Walder’s edited collection (1993, 2000) dubbed them, gave way later in the 1970s to solo-authored, deeply conceptual and more cerebral work, particularly Dimetos (1975) and Orestes (1978). This should not surprise anyone who has witnessed the range of forms that Fugard has traversed in his career, from journaling (his published Notebooks make for fine reading), to fictional prose (Tsotsi, in its original form as a novel), to memoir (Cousins, too, is riveting), to film-writing (The Guest, Fugard’s dramatic rendering, with Ross Devenish, of the classic Afrikaans poet-naturalist Eugène N. Marais’s morphine addiction, based on an episode in Leon Rousseau’s biography of Marais), to still other modes of expression in addition to playwriting. Indeed, Fugard embodies the protean creative spirit, refusing to be pinned down or restricted, and this is of course a version of the writer’s greater spirit of refusal, making him a classical humanist despite the “posthumanist” climate of the times as he entered his sixth and seventh decades, and, in the 1990s and 2000s, continued to write from the (defiantly human) heart, undeterred.

This is not to say that his work after the collaborative, cross-racial “township” phase was not politically engaged. Despite Fugard’s own frequent disavowal of the term “political,” plays like A Lesson from Aloes (1978), “Master Harold” ... and the Boys (1982), The Road to Mecca (1984), and My Children! My Africa! (1989) continued to home in on the predicaments of defiant individuals seeking to reinvent themselves in ways that particular circumstances, both material and moral, rendered next to impossible. In Playland (1993), the desire to regain a state of free human “play” is set in the context of two characters’ haunting by the murders they have committed in racially defined conflicts and lodged in a past that won’t go away, despite the “playland” of the looming post-apartheid era. In this drama, however, “Playland” is a cheap traveling carnival, more show than substance, and Fugard here sets the tone for an aptly ambivalent reading of the post-apartheid period, as his later plays would reaffirm. The future, this play suggested, is as much in the past as anywhere else, and the past is every bit as uncertain as the days ahead, as becomes apparent in plays like Valley Song (1996) and its sequel, Coming Home (2009), in which Fugard takes on the human consequences of former president Thabo Mbeki’s disastrous AIDS denialism.

***

It is beyond question that, from about the year 2000, Fugard’swriting becomes more reflective and autobiographical, as if he is allowing himself some respite from the responsibilities of an artistic selflessness that his work carried aloft so vigorously for over forty years. The Captain’s Tiger (1999), Sorrows and Rejoicings (2001), Exits and Entrances (2004), and Victory (2006) are good examples of situational complications in which Fugard allows his own stories, and his artistic persona, to enter more freely into the picture. It is also true that many critics detect a waning in the powers of the great playwright’s work in the post-2000 period. Laurie Winer, reviewing a production of The Captain’s Tiger at the La Jolla Playhouse in the Los Angeles Times in 1998, comments that “Fugard sets the stage to address his long-ago failure of nerve [to tell the first story he ever attempted to weave in writing], and then politely declines.... Fugard instead gives us just an amiable exercise in nostalgia.” Charles Isherwood, writing in the New York Times about a production of Exits and Entrances (2004), comments drily that the two-character play “is not a major addition to this South African playwright’s oeuvre.”

Such respectful diffidence becomes fairly commonplace in reviews of Fugard’s late plays, occasionally giving way to strong disaffection, such as is evident in John Simon’s scathing review in New York magazine about The Captain’s Tiger at the Manhattan Theater Club, opening his account with the rhetorical question: “So, you think you know what boredom in the theater is?” What follows is not pretty for Fugard fans. In The Telegraph of London, Charles Spencer’s review of Fugard’s Victory (2006) at the Theatre Royal in Bath was equally unsparing: “This is a desperately sad play, partly because its author Athol Fugard is writing below his best form, but largely because of its anguished pessimism.” Spencer closes his review with a rueful reference to “this exhausted and despairing play.”

Equally, it must be said that Have You Seen Us? (2009), Fugard’s first play set in the U.S., and a premiere at Long Wharf in New Haven, got panned. In the New York Times, Isherwood called it “a distinctly minor addition to his renowned and influential canon” and “an anecdote worked up into a drama.” Sandy MacDonald (Theater- mania) called it “a thin, staticky mewl, like that of a faraway radio station playing a vaguely familiar, once-popular tune.”

Despite such notices, Fugard’s late work has continued to find traction, as is evident in more favorable reviews of plays like Sorrows and Rejoicings and Exits and Entrances. The line between a profound simplicity that creates universal recognition, on the one hand, and sentimental cliché, on the other, can be very tenuous, and derives perhaps from historical specificity, or the bond between time, place and story. It is unfailingly hard to find the perfect pitch, no matter how many times one has done it before. Fugard seems to have found this note in his 2010 Long Wharf production, The Train Driver, which is a theatrically bold “outing” of inner guilt and complicity, borne for decades by a tortured “white” South African conscience. (The parallels with Fugard’s own situation are of course overt.) The train driver in question was driving a carriage when a black woman jumped to her death in front of the head-locomotive. The infant strapped to the mother’s back was also killed. For many Long Wharf Theatre patrons, Fugard’s work had by 2010 become something of a draw for the regional theater, and The Train Driver was an example of the unusually frank reckoning that had perhaps become the hallmark of the playwright’s late or “U.S.” phase, culminating in his marked preoccupation with beginnings and endings in The Shadow of the Hummingbird. In the New Haven Review, Donald Brown wrote of The Train Driver: “[I]n its stark drama, [the play] asks us to feel for a moment as shattered as Roelf [the train’s driver] ... as at a loss to deal with the violence of the world except through words that find a voice for what no one ever says.” While finding the messages in the play at times too banal and lacking in subtlety, Christopher Isherwood in his review of a 2012 production, directed by Fugard, allowed that the play “makes a modest but eloquent addition to Mr. Fugard’s oeuvre,” citing its depiction of how people “separated by great social divides can, through the power of the imagination driven by empathy, feel their way into one another’s lives and be changed by the process.”

Indeed, finding the means to make his audiences feel, and never to give up on feeling despite neoliberal consumerism run rampant, remains imperative for Fugard’s spirited rebellion against the common view of things. In an interview in 1989, he said: “The most immediate responsibility of the artist is to get people feeling again.” And, true to his lifelong mission, he refuses to let up. If there’s nothing else one takes from later Fugard, then it is this near-blind determination to continue doing the hard thing. And it’s as profoundly difficult as it is simple, because it’s in the performance, the doing, that increase is achieved. In the Long Wharf production of The Shadow of the Hummingbird, the playwright’s ability to evoke poignant feeling, and to provide cathartic entertainment, was beyond any doubt. If Athol Fugard does ever stop, it will certainly not be for want of the quality of spirit that his work both engenders and evokes, defying the all-too-evident reasons for pessimism that are all about us, always.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project