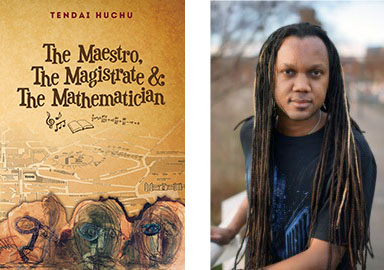

Dostoevsky’s book Demons, about an intellectual “circle” in pre-Revolutionary Russia, is a novel of ideas. This is not a term one hears thrown around much in the many current debates about African writing, and with good reason. “Ideas” seem much less central to the questions with which African / not-African / Afropolitan / global authors and critics are concerned than things like story, identity, or politics. The emphasis on ideas as something distinct from their human vessels, though, is a big thing to lose. Thankfully, the Zimbabwe-born, Edinburgh-based novelist Tendai Huchu’s new book reminds us that serious thinking is as important as driving home what we already know.

The Maestro, the Magistrate, & The Mathematician in fact alludes to Dostoevsky in one of its most provocative references. The book is structured as three separate plotlines that ultimately converge in the Zimbabwean diaspora’s party politics. One of them, The Maestro’s, tracks a grocery-store worker through his increasingly febrile reading habits. As he descends (or Dostoevsky might say, rises) into a state of social alienation and intellectual agitation, he likens himself to Kirillov, the character from Demons who theorized about and then committed a “rational” suicide. Kirillov’s motivation was to kill himself as a means of attaining ideological fulfillment, instead of out of fear to go on living a meaningless life. He believed that this could “kill God,” and Huchu’s Maestro likewise ponders the theological problem of free will: “How could a human being do anything other than what God already knew he was going to do? And if God did not know the future then God was not omnipotent.” This scene captures the achievement of the book as a whole, in the sense that it links characters in recognizable social dilemmas with deep-seated structural contemplation.

While literary conversations these days tend to focus on how writers themselves are represented, Huchu takes risks with his technique of representation. One of the most woeful lacks in politically correct reading (which does lots of good things, too) is a distinction between stereotype and type. Types are essential to crafting a broad social canvas; they forge legible figures to act as both characters and commentary. Huchu’s typological palette is formidably broad: the other two plots of his novel are about, respectively, a distinguished former judge who now works in a nursing home, and a hip young economics PhD student. They are hilariously rendered through their foibles and self-parody, in a style that is incisive rather than lyrical. The Magistrate is horrified at men being present for childbirth, and The Mathematician sticks to a “four-week rule” for not going without sex. In those plots, especially, Huchu’s eye for social rather than subjective precision pays off in humor with real edge. Without giving too much away, the perennial favorite question of race’s relation to animal rights comes into the picture. (For once, it does not involve dogs.)

This combination of hilarity and social-intellectual zing carries through the novel’s depiction of Zimbabwean politics, as well. One of Huchu’s best scenes takes place at an Edinburgh MDC rally, which gets off to a late start because someone forgot the keys to the building it’s held in. When a local councilor (who is confused with the mayor) shows up to “make a speech” at the MDC branch chairman’s request, he is disoriented by a succession of puffed-up Pamberi!’s, and an only half-remembered Zimbabwean national anthem. A page later, Huchu narrates what he manages to glean from the affair:

- There was a man called Robert Mugabe.

- Mugabe was a bad man.

- Mugabe must go (although it was unclear exactly where to).

- Mugabe was ‘killing peoples’.

- The BBC had something to do with it.

- The chairman was prepared to die for his beliefs.

- Mugabe must go now (see 3).

- Mugabe must stand trial and be found guilty.

I am laughing so hard as I copy down this excerpt that it seems criminal not to confess it.

Finally, The Maestro, The Magistrate, & The Mathematician manages to capture African diasporic realities without over-playing the extent to which “diasporic identity” determines people’s views. The Magistrate falls from socioeconomic grace in his relocation to the UK, but his core values and frameworks remain avowedly Shona. The Mathematician, too, continues to measure his social standing by what’s happening in Harare: he has a working-class white girlfriend and he’s clearly the one on top, with frequent flights home and phone calls from his father about market predictions. (“Dude,” he says at one point to a nostalgic friend, “niggas ain’t had it this good in 300 years and you wanna time travel back to the 50s? Shiiit, you’d have wound up in some township being tear gassed and having dogs set on you by those motherfucking Rhodies.”) It is similarly refreshing to see so much Shona in a novel without translation, and yet also without hindering the reading experience for people who don’t know the language.

By the end of the book, suffice it to say that Huchu arrives at a somber note. On the way there, he crafts moments of real human poignancy (such as the Magistrate’s reunion with his wife), but never veers into cheap valorization of either hope or despair. In its model of interconnectedness instead of “mobility,” the only recent novel from or about southern Africa that recalls it is Imraan Coovadia’s Tales of the Metric System. These two are almost in a conversation all their own, and it is one we should hear much more of. The Shona saying for a “breath of fresh air” is mhepo ino tonhorera, and Huchu really is.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project