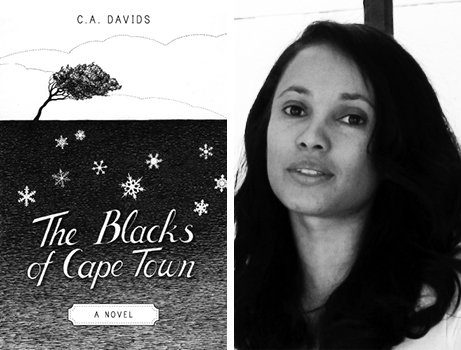

The Blacks of Cape Town by CA Davids, Modjaji Books, 2013.

On the cover of CA Davids’s The Blacks of Cape Town, a windswept tree bends towards the earth, which, patched by snowflakes, is drawn in shades of grey. For this reader, the indeterminacy of grey evokes the ideas with which the novel grapples: the ambiguities of skin and of betrayal, and of finding one’s place in social and filial narratives where much may be hidden. Juxtaposed against the slippages of identity suggested by grey, the book’s title seems to offer a clearer meditation on “blackness” and its personal and political significances. Or does it? In what follows I argue that at its best, Davids’s writing works against assumptions about the histories and identities we claim, revealing the tangled skeins of complicity that lie beneath their surface.

Protagonist Zara Black is a South African historian fleeing a family secret and working at an industrial-size university in the U.S. during Barack Obama’s election to the presidency. The profoundly racialised discourses attending Obama’s campaign, election and tenure mirror Zara’s recollection of her childhood under late apartheid. It is a layering of public history with personal narrative that conveys the intimate weaving together of private and public, and will prove the downfall of three of the novel’s characters. Is it worse to betray a friend or to betray a movement, and is it worse to do so out of feeling or ideology? In a series of temporal shifts, Davids leads us through two such betrayals. The first is by Zara’s grandfather Isaiah, who denies and abandons his mother by passing as “white” at a time when the physiognomies of race – hair, eye colour, skin – were obsessively documented. Perhaps in atonement, Isaiah takes on the surname “Black” after his move to Cape Town. As the novel’s central motif, “Black” becomes a signifier for the painful history of race, individually and collectively, locally and globally. In his recent piece on Davids for the Mail & Guardian, Percy Zvomuya observes that the book’s transatlantic intersections speak to a genealogy of (one-sided, it must be said) exchange between black South Africa and black America. Here, the novel’s transnational impulses – South Africa mapped onto America mapped onto South Africa – resonate with other recent fictions seeking to locate South Africa within globalised flows of peoples, knowledges and power.

For Zara’s parents, “race, as important as it was in South Africa, was also simply unimportant. And even when they were forced to declare race – black in unity rather than coloured as they were technically classified – privately, Zara’s parents still held the truth” (37). Blackness is politically exigent, but it is not the summation of a person. In America, Zara’s Asian, African and British ancestry belies the neat categorisation that the state seeks to impose upon her. The naturalisation of historically constructed racial categories is contested throughout the fiction, and it’s preference for plurality echoes scholarly work that figures the Cape as a site of creolisation. Davids clearly knows her academic stuff. Concomitantly, re-evaluations of the adequacy of race as an organising concept, are challenged by a contemporary of Zara’s in the States:

“Well tell you what, I’ll talk ‘post race’,” Pedro replied, “when people no longer lock their car doors as I walk by … post race!” (127)

What the novel does well is to hold these critiques in tension while remaining alert to the particularities of local history. This is convincingly achieved in the South African sections, as evidenced by Davids’s reading list on Victorian Kimberley and Cape Town. Historical grounding provides a depth that is sometimes uneven, for though the transnational purview is to be commended, it doesn’t always hold up. Zara’s relationships in America with her colleague Ling and lover Michael for example, seem flimsy in comparison to the more richly textured South African scenes. They read as props to action that is happening elsewhere. So the reader finds herself skimming over the American chapters in search of Zara’s family and the densely threaded narratives of their lives. Davids writes beautifully of Cape Town and the family home built by Isaiah at the base of the mountain, “Squares of white stone, yellowing in the Cape Town sun, green tin roof rattling only occasionally, as it caught a channel of cool mountain air” (7). The house holds the memories and feelings of the family: courtships, sibling rivalries, affairs, triumphs and losses. Davids’s descriptions of the house and the relationships spun within and around it have a real luminosity and demonstrate that large themes are engaged most powerfully through the small intimacies and encounters of the everyday.

This leads me to the form of the second betrayal: a government letter in which Zara’s father Bart is retrospectively declared a traitor to the anti-apartheid movement. Here then is the reason for her flight to a country no less beset by its past than our own. The unraveling of the letter’s secret is the novel’s motor. I won’t reveal it here, but it is cleverly executed and turns upon a neat meta-textual trick about the nature of storytelling and truth telling:

This great struggle of ours – my God, what a legacy it has left us: we must not see anyone but the victor, the hero, the winning narrative. No, we have painted over the past as it was, and replaced it with something which is pleasing to the eye. A one dimensional story! (222).

In shades of Hayden White, Davids invites us to consider practices of reading and writing, and their enmeshment with the production of history; that the validation of some stories over others engenders particular versions history. The textuality of history – as novel, letter, documentary, archival material – prompts us to reflect upon our own role as readers. How, Davids asks, might we read and write in ways that bear witness to the multiplicity of stories? How might we acknowledge and learn from our past without letting it crystallise into sanctioned scripts of “the winning narrative” that elide its dangerous complexity?

This is a smart novel and one I highly recommend. It is thoughtful, carefully constructed and often poetic. But I wish it had allowed these difficult questions to linger, rather than seeking to resolve them. In what must be an intentional echo of wider national processes, Davids closes the book with a gesture of redemption, “Let us each forgive” (236). This conclusion facilitates a poignant re-connection with Isaiah’s house, allowing Zara to find her place in her family’s story and, by extension, that of her country. It’s a tender ending, but one can’t help wondering what might have been gained had some of the uneasy ambiguity of the earlier chapters remained. Is it possible, or even desirable, to arrive at closure? Can we ever be, as it were, “post-past” or ought our ghosts to remain with us, agitating us against forgetfulness?

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project