The Long Walk to Freedom movie was never going to have a particularly easy time of things in some quarters. In this era of acerbic Africa Is a Country editorials and 140-character twitter-intellectuals, any portrayal of African subjects is going to provoke close scrutiny and a vinegary cynicism. And what more African subject could there be than Nelson Mandela? It wasn’t the movie’s fault that the world’s greatest modern statesman died while it was in the first rude weeks of its premiere, but the passing of Mandela could only throw greater scrutiny on a movie which attempts to tell the definitive story of his life.

The mourning period saw the television and radio networks being flooded with documentaries about the life and times of a man who had, in the true winter of a life whose autumn had been uncharacteristically long, vanished from public view to be replaced by images and ideas. There was no small amount of memorialisation even before Nelson Mandela died, but the name that had for so many years stood for ideas of freedom and reconciliation, also began attracting images and ideas that weren’t so appealing

So, into the miasma of family squabbles and the quite-unresolved issue of what Mandela means to us, comes an adaptation of his autobiographical Long Walk to Freedom, from the director Justin Chadwick. As Mandela’s story is one that has been storied and archived in numerous ways – there are photo exhibits, coffee table books, and uncountable documentaries – it’s easy to overlook that Long Walk to Freedom was the first comprehensive telling of his story, a narrative that was begun in dire times and smuggled from Robben Island. The transition from black ink to screen – complete with pre-movie message from Gareth Cliff compelling us to “continue the conversation” using a trendy Twitter hashtag – has not been a successful one.

To be sure, this film comes up short in all the usual ways, but it is all the more curious for that. Why have they struggled to tell this most South African of narratives? In Chadwick’s film, we have Mandela as hero figure, of course. The problem seems to be that the hero narrative such a film requires doesn’t sit very well with what we know of Mandela’s story. The biopic genre further restricts the possible creative directions the narrative can take, and the result is a movie that tries to do a lot but ultimately does not succeed in rising above the textbook facts to give us the story of this larger-than-life man. At every point, the discerning audience member feels dissatisfied, goaded by annoying inaccuracies, and manhandled by soaring strings doing their frenetic best to convince us that this is the story as it should be told. It isn’t.

The first and most major problem is that since Nelson Mandela was always at pains to point out how his story is a communal one, a story of those who influenced him as well as his grounding in the movement, it is a little odd to encounter in the film a Mandela who seemingly springs self-formed from Hollywood-does-the-Eastern-Cape. Much like Joshua Michael Stern’s* Jobs, another film which perhaps came too soon after its subject’s demise, Long Walk to Freedom feels rushed. Of Mandela’s formative years under the aegis of King Jongintaba, we are granted only a vague montage of herding and initiation rituals (John Kani’s son appears for a brief moment as the post-ritual Mandela). We learn nothing at all about his education – so there is nothing to explain how Mandela progresses from blanketed initiate to the poshly-suited city-slicker who takes up the bulk of the film’s action.

A re-editing in a different time would perhaps have seen this movie being called “Mandela”, because the walk to freedom it shows is purely his own. With a callous disregard for historical accuracy, the movie flattens many important elements of South African political history into mere symbolic backdrops. So the men who lionised the ANC, Walter Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada and Oliver Tambo, become quite voiceless supplicants, appealing to the broad-shouldered boxer to help deliver the people from their oppression. All the white people shown in the film are either monstrous barking racists or sinister Broederbond types in eighties suits. There are other, more subtle ways to show how the coloniser is deformed by his/her hatred.

The film is at pains, or wants us to believe it is at pains, to show us that “Mandela was no saint”, a clichéd idea that finds expression in odd ways: while Mandela is single-handedly revolutionising the ANC (the movie’s merry disregard for historical accuracy is heinous), we also see him as a wife-beater and casual philanderer. There is no depth to these depictions and they feel like they were inserted slap-dash into the hero-narrative because they have to be there, rather than because they add anything.

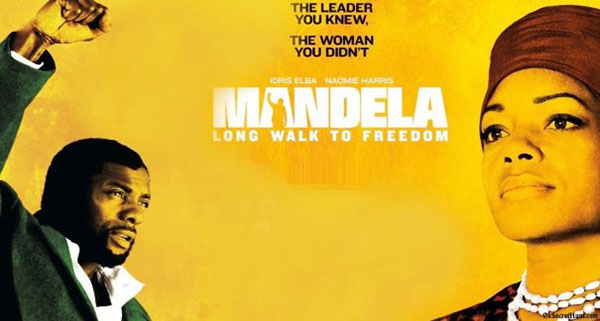

Idris Elba’s adult Mandela is a workmanlike effort that never quite settles into its stride. While at times he gets the accent quite right (even managing a little bit of Xhosa), it too often sounds like a British person’s idea of Mandela’s voice, which is a pity, because Elba is an entrancing actor who brings sensitivity to a daunting role. Elba’s physicality takes Mandela’s slightly wooden demeanour and towering stature, and transmogrifies it (via the endless hero shot) for a modern audience, so that he becomes a sort of sensually lion-thewed Rambo-figure, all glistening muscles and intense concentration as he pounds his boxing opponents with the same steely determination that we must presumably accept will also characterise his politics.

The Robben Island years are dwelt on at some measure, and the film highlights the emotional and physical difficulties of those years, as well as the rise of the angrier and more militant student activist types. The movie does well here to condense a lot of history into an easily perceived sequence, although there will be grumbles at how Mandela’s comrades on the island, his valued friends, receive little screen time even here.

The movie grants no generosity, either, to its portrayal of Winnie Mandela. Played by a British actress of inappropriately slight build, it’s not enough that she gets the voice and accent tiresomely wrong (There is evidently only one reference point for “female African accent” for the international film industry, because Winnie sounds here like Sophie Okonedo’s character in Hotel Rwanda). The major problem is that she is portrayed as a repellent figure overwhelmed by an Ahab-like malice, from which our lumbering hero must rescue South Africa. While some attempt is made to represent the trauma Winnie suffered – “what they have done to my wife is their only victory over me”, Mandela says – the depiction feels too uneven and schizophrenic. Furthermore, although the movie goes some way in depicting the under-examined civil violence that tore through South Africa between 1985 and 1994, it takes on a decidedly sentimental tone, and here again the pace speeds up, as if to prevent watering down the chronological thread.

These are the most obvious flaws, but overall the film’s greatest flaw is that it doesn’t feel authentically South African. It’s hard to be enthusiastic about a film that feels like a cross between a beer advert and Gladiator. It’s a problem summed up at the end of the film, when the credits roll and the end music is supplied by Bono/U2. This feels like a shallow waltz through the life of Mandela, glibly polished for the attention of an international audience. It reduces Mandela even as it tries to show us what a complex man he was. Perhaps it’s that the movie is so showy where subtlety would have done more, and so blasé when explicit links should have been drawn, that it leaves the watcher alienated. Long Walk to Freedom, as it is adapted here, is not our story.

[*This review was edited on 29 January 2014]

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project