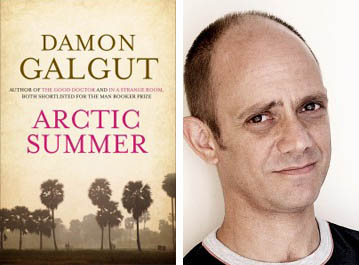

Arctic Summer by Damon Galgut, Atlantic Books, 2013.

Damon Galgut occupies a unique place in the South African literary scene. His work – 7 novels in all – explores complex ideas of identity, with often uneven results. His late writing, particularly, has taken on the placeless timbre of a world writer, but he has received a curiously muted reception in most quarters. In Arctic Summer, Galgut’s latest novel, he turns his attention to the life of the writer EM Forster. In sparing yet flavourful prose, he compacts a tremendous amount of research into a neurotic and touching narrative about the repressed desires and secret longings of a man who kept his love life a secret for most of his life.

The novel proceeds at a storyteller’s lento, with the familiar stations of Forster’s life being dropped or dipped back into and woven into a tapestry. Galgut has imagined the life of a man of who Katherine Mansfield once said “never gets any further than warming the teapot.” One can sense that his goal is to invest character to an author who has always carried a whiff of the middling about his sensibilities. The temptation is to infer an overlap between Forster and Galgut’s understated position as a South African man of letters, but that does not diminish the stature of this work.

In some respects, Arctic Summer is a conventional historical novel. The novel draws its title from an unfinished work Forster began in 1909. We meet a young Edward Morgan Forster (he goes by the name Morgan for most of the book) aboard a ship bound for India. The narrative splits early, digressing often to fill us in on the stations that make up Forster’s life, before doubling back to the main path of the journey from Howard’s End to A Passage to India and beyond. We witness him meeting Syed Ross Masood, the man whom Forster loved in a capacity which, if not quite unrequited, was physically unfulfilled. The pair’s friendship, which skirts the repressions of Edwardian English society, is a marker of Forster’s odd relationship with the world. Morgan’s friendships (and deeper relationships) with men, whose eccentricities or class/race positioning excludes them from the normal world, are given a finely-grained texture through Galgut’s writerly attentions.

To be sure, it is a complex story, overflowing with remarkable attention to detail. There is much digression – not all of it necessary – but Morgan’s actions and his inner turmoil are given voice by understated narration in free indirect style, the tone of which makes Arctic Summer feel like a well-scripted documentary narrated by Stephen Fry. Galgut employs retrospect to great effect to give full nuance to the many facets of Forster’s life that contributed to his creative process.

But Arctic Summer elevates itself above its sometimes plodding narrative, with a vitality that speaks through its protagonist. Forster is brought into life on Galgut’s pages by brief bolts of characterisation. We read of Morgan being repulsed by the bigotry of the English (“they assumed that he shared their feelings, when most of the time he did not”) and unable to connect with the natives even as the landscape of India or Alexandria beguiles him. He resides between these two fragments, seeking the empathetic identification he would later sum up in Howard End’s famous phrase, “only connect.”

The failure of the world to practice such empathy gathers in scenes such as when Morgan’s mother, with whom he has a strained closeness that borders on the Oedipal, cuts him down for being too polite:

“You are like your father. He always put his foot down at the wrong time, like you.” She paused to rummage in her handbag for her lozenges, before murmuring a final judgement: “He wasn’t a strong character.”

We notice the way the writing moulds itself around its subject. The wounding slights (and Morgan feels every slight levelled at him) and petty discriminations of the English both at home and abroad are particularly well-written. It’s a recognisable world in our age of Downton Abbey and other period dramas, but it’s no less remarkable for that.

The novel hardens around the writing of A Passage to India, Forster’s magnum opus, but it takes in the author’s oeuvre as well, displaying a formidable knowledge of Forster’s other works. We see how the writing of Forster’s more risqué novels (Maurice, in particular, would not see publication until 1971, after Forster’s death) occurred in a maelstrom of havering and self-doubt. Galgut’s narration never lurches into moth-eaten pastiche or parody as it renders the heady hurdy-gurdy world Morgan experiences. In particular, his struggle to come to terms with his homosexuality is written in ways that make it clear both how much has changed, and how far there still is to go in our treatment of difference.

Forster’s relationship in Alexandria with the poor tram conductor Mohammed el Adl is rendered sensitively and with scrupulous attention to how the dynamics of race and class come to bear on the men. And the cruel rejections Morgan suffers veil themselves in the stiff Edwardian language while beneath that surface, Morgan’s frustration and loneliness flare fiercely. Galgut has a very good eye for this subtle game, and the even more impressive ability to integrate that seeing with Forster’s.

Similarly, Galgut’s representation of Forster’s time in India strikes just the right note. An example might be in the sparkling passage below, when Morgan witnesses a festival to celebrate the birth of Krishna:

It was best, perhaps, simply to be carried by the current of events, and let understanding follow in their wake. The entire court decamped to the Old Palace for the duration, leaving shoes and meat-eating outside. Nothing was supposed to die as long as the festival lasted; not even an egg. A room was made available to Morgan upstairs, which did offer some sanctuary, though the mayhem leaked in at all hours, and there was a holy feather-bed in it which required votive candles burning on the bolster and the prayers of the Maharajah once daily. Sleep was in any case disturbed and intermittent, because of the three bands playing simultaneously in the courtyard in a Gazebo and the terrible thudding of the steam engine which drove the temporary electricity supply.

In the daytime it was much worse. In addition to the bands, groups of singers, accompanied by cymbals and a harmonium, offered unending prayers at the altar. Sometimes an enormous horn was blown; sometimes elephants would trumpet. Between all this came the sound of shouting, or the patter of children’s feet as they ran and played through the palace. But the racket was merely an accompaniment to a corresponding visual cacophony: people swarmed and rampaged everywhere, the altar was buried in petals, incense burned smokily.

This passage is in danger of tripping up the complacent reader – what we are being given here is not simply a tour of the strange universe in which Morgan has immersed himself, but how Morgan himself experiences it: the difference between the author reprising orientalism, and representing it in a way that highlights the problems of such a view.

And that provisional, embarrassed perhaps captures Morgan’s character perfectly, the shy and reserved Englishman allowing himself to be carried along by a world he doesn’t quite understand. “In Such disorder, what sense?” he asks himself, and we know the discomfort of a sensitive soul in an unfettered world. Galgut gets the tuning of the novel’s machinery just right. He doesn’t try to imitate Forster’s writing style: doing so might have drawn unwelcome comparison to Forster’s work. Instead, Galgut’s novel distils what is so recognisable about Forster – the uncertainty, the peremptory appearance and disposal of characters – and renders them in modern colours. Forster’s intrigues appear to us as they would to a reader of his time – that is to say, modern and up-to-date.

Here, Galgut resists a common mistake that bedevils many such novels, which we read through a scrim of retrospect. His characters, mostly moustachioed men of Empire, are not the sepia-toned caricatures they could very well have been. Real-life literary characters – Henry James, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, Cavafy – appear on stage in a variety of sketches, and they have eloquent if ordinary conversations about writing and creativity. As Morgan ages, so the prose grows weightier, the transition from the sprawling disorder of India to the accumulating losses of middle-agedness managed in solemnly exact prose.

Rarely does Arctic Summer allow itself to seem indebted to other novels – though JM Coetzee is never too far from view, especially in the last chapter, the closing of which is redolent of the end of Disgrace. And of course, Galgut seeds references to A Passage to India into his text, the better to reflect the involuntary nature of inspiration. The effect of this is to cast new light on Forster’s work. The genius of Galgut’s novel is what it does: Forster’s novels cast about for truthiness. Galgut’s Arctic Summer shows how that search characterised Forster’s life as well as his art. The pleasure of reading the novel comes in recognising how the affective capacity of Forster’s finer writing is fleshed out by Galgut’s sense-making.

It came as an unhappy surprise to many that Arctic Summer, which was tipped for the Man Booker Prize, was left off this year’s longlist. Despite that, Arctic Summer is certainly an exhibition of an author at the height of his formidable powers.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project