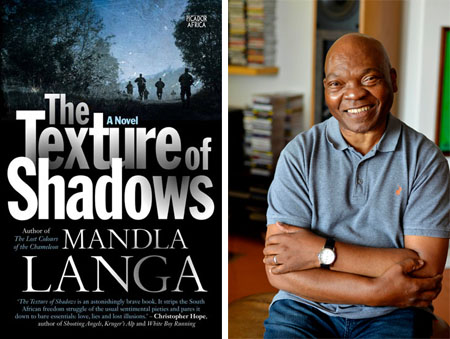

Mandla Langa’s book titles always seem to me to get ‘under the skin’ of his novels. Think, for example, of Tenderness of Blood, The Memory of Stones or The Lost Colours of the Chameleon. His latest novel – The Texture of Shadows – has no less an evocative title. And, after all, what is the texture of shadows? What does it look like, feel like, sound like? Where does it lead? And who or what does it belong to?

In the novel, which traces the movements of a group of exiled People’s Army soldiers from Angola back to South Africa, Langa explores the texture of shadows from a number of perspectives. The narrative begins with a prologue: a letter from Chaplain Nerissa Rodrigues addressed to the President in which she covers two aspects; “one, the possibility that we, as a Movement, might have been remiss in our treatment of people incarcerated in our camps – especially Sector 37; and two, the idea of starting a process to locate the graves where our young men and women might be buried on foreign soil” (p.1). The shadows summoned in this sentence are at once personal and national, past and present, fact and fiction – the dualisms of South Africa’s history which creates the suspended tension throughout the story.

Set in the years leading up to Nelson Mandela’s release, we are introduced to MK guerrillas Django (aka Ezekiel Zimo, also called Hickory until recently), Mchinda (aka Sidwell Zondi), Sassafras (aka Thabo Stone), Stinkwood (aka Rex Mabena) and Pomegranate (aka Refiloe Mokoena). These five men form part of a larger group of twelve when we meet them crossing “the border from Botswana into South Africa at the shallowest point of the Pitsane Molope” (p.9), carrying two heavy trunks. Commander Mahogany does a mental roll call for the reader: commissar Baobab (check), Imbondeiro (check), Hickory (check), Linden (check), Pomegranate (check), Stinkwood (check), Avocado (check), Walnut (check), Tamarind, Pistachio, Sassafras (check, check, check). Twelve shadows accounted for, but we are only to learn the true names of five, and only much later when the group is safe, after they have been ambushed and comrades are left dead in the night, shadows without names. How many other soldiers were lost in this way? How many families – to this day – cannot account for family members? This, then, is part of the Chaplain’s quest because, as she explains, “We don’t believe a soul has found its place of rest until the dead has been mourned according to custom” (p.226). But who can mourn for a shadow?

These are the questions intimated in Mandla’s text as he takes us back in time, when rumours about the imminent release of Nelson Mandela have reached fever pitch. The country is in turmoil and it is precisely this state of emergency which leads to a collusion between General Palweni – the man in charge of Commander Mahogany’s unit – and Jan Stander, member of the South African security police whose mission involves, in part, recruiting MK soldiers as apartheid askaris. Here we meet Jolene, a ‘platteland meisie’ and Strella, a deadly sniper, and it is, especially, the story of Strella that evokes the shadows of South Africa’s violent past (and present) and which lends nuance to the novel, disrupting the more general ex post facto ‘haloing’ of the freedom struggle.

But we also have to make sense of the pact between General Palweni and Jan Stander or, to be more specific, the General Palwenis and Jan Standers of the pre (and post) rainbow nation state. These people were (and are) “the big brains, men and women with political muscle and influence” who steered the machinery of apartheid into democracy. It is a compromised state from the start, and it is the shadow of this compromise which haunts the country’s present. But, as General Palweni tells us, “We have to use modern means to meet our objectives. If that makes me a warlord, so be it. In my heart of hearts, though, I see myself as a patriot” (p.238). It is this kind of insight that renders Mandla Langa’s novel so complex: every politician is a traitor to some extent – a warlord – and every single one of them views her/himself as patriots. They are the people who can be traced in alliance to “the development of the conflict in Angola”, to “the different warring parties, UNITA, led by Jonas Savimbi, our friend, allied tenuously to FNLA, our bigger friend, against MPLA, definitely not a friend and run by communists and aided by Cubans and Soviets” (p.243). They are also oftentimes common folk fighting, simply, for a better life. But the machinery, as Langa shows, is far too sophisticated and regulated to allow for true, unscathed heroes.

Told from different perspectives, the reader is faced with the same events over and over, filling in the gaps while concurrently being presented with more shadows. This narrative strategy allows for a kind of remembering – an accounting for – that which is lost in battle: people, but also dreams and hope, innocence and faith. It also forces the reader to look repeatedly at the skin game of politics: what is exposed, and what lies beneath. And it is in search of that which is concealed that Nerissa Rodrigues finds herself investigating Sector 37, a ghost camp governed by Nozishada, rumoured to be torturing prisoners.

Besides the more obvious strands and themes weaving in and out of each other, the novel also touches on homosexuality, the complicity of the guileless, cultural practices, the labyrinthine qualities of memory and forgetting, and the complexity of racism in South Africa. It is a dense plot; one which demands thoughtfulness and responsiveness from the reader. And though there is some resolution, some sense of accounting for, a number of aspects remain – as in life – shadows, hinging on the edge of history. But whose history?, I hear Mandla Langa asking, whose history is casting the light?

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project