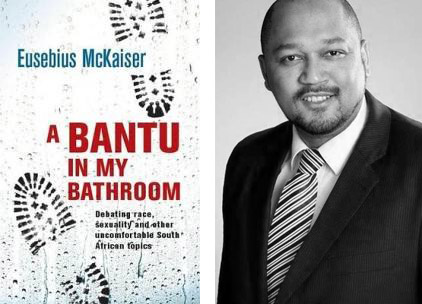

A Bantu in my Bathroom: Debating race, sexuality and other uncomfortable South African topics by Eusebius McKaiser, Bookstorm, 2012.

Eusebius McKaiser styles himself as a liberal critic of liberalism, the whole and admirable urge of this volume being to search out the limits and contradictions – an intellectual horizon – of our dominant political mode. His engagement begins with analytic philosophy – you can mark the dry “if this then that” style – but unlike that discipline, too often unanchored with abstraction and metaphysics, he marries this to a racial consciousness, a bodily and experiential dimension: that abstract systems of power and domination are, finally, lived and felt by the raw, human pulp of Empire. Yet, McKaiser makes for a curious essayist. In fact, “curious” is the milder of adjectives in this regard, in service of a social decorum I feel myself already careering to ignore. To resist euphemism, then, McKaiser is an infuriating essayist: haughty and pompous, his language is near-inert except when gracelessly lurching into the realm of a dire anti-poetry. Among his literary affectations are building up sentences into a madding climax, before declaring a quaint “not so” or “not quite”, with all the charisma of a private-school headmaster.

It is not simply a matter of stylistics which damns this polemical collection, but also a matter of argument. McKaiser descends from the tradition of the Oggsford debating league, and he carries his arguments through with the same populist principles of the medium: fortress your position through affective rhetoric, cloister yourself by winnowing your opposition down through representing only the weaker strains, occluding or ignoring the more complex ones, caricaturing the rest, but most importantly presenting tentative conclusions as though there were no other alternative (it makes it ambiguous to say any of this, because his tentative conclusions are, on the whole, correct and valuable).

Any ambition to properly engage his subjects is also curtailed by a problem of format – these essays, roughly around ten pages each, and all of which take a contrarian perspective on a fraught social issue, do not have the patience to fully test their hypotheses, and thus come across as premature excursions. The result is a sequence of limited provocations, which enflame the imagination excellently, but then often fail to offer up the situation in its full and churning complexity. And among all this, McKaiser builds up a literary personality that is smug and self-assured, condescending, almost auto-erotic in its evaluations of its intelligence, self-aggrandising autobiography intruding into his arguments.

This is a terribly cynical appraisal, delivered in generality, so I might temper the criticism by remarking on what McKaiser does well. Bantu is split into a tripartite structure of “race, sexuality and culture” and the author develops a series of short, independent essays which journey through such questions as affirmative action, polygamy, animal rights, comedy and art – in short, the sorts of divisive issues which fracture the South African imagination, especially given the fact that he uses racial and cultural imperialism as the connective tissue between them.

McKaiser is engaging in that his essays are largely conscious of history. He re-histories the forgotten narratives which define the present condition, recovers the memories which are often repressed, and so is able to offer up an understanding of “structure”, the implicatedness of things, which might allow him to unite these distinct issues under general rubrics of power, domination and exploitation. Importantly, he generally takes the counter-hegemonic position and produces the kind of frictive tensions that stimulate the best arguments.

His own positions, however, are not terribly new, and the perfect audience of this book then really becomes the kind of cerebrally-dulled sitcom-watchers who have genuinely never bothered to think about the systemic nature of oppression. To anyone who is capable of thinking reflexively or combatively on these issues, there is no insight here beyond the border of the obvious. And this point needs to be made assertively, because McKaiser’s tone suggests that he believes himself to be the inaugural champion of these ideas. Unlike his radio personality, which benefits from a warm and gracious voice, his writing is unlikeable, alienating and even when he aims for humour, the result feels less organic and more functional – like machine-generated comedy, aware of the principles of the art, but not the social dynamism required for its delivery.

This review is in danger of becoming schizophrenic in its alternate desires to praise and loathe. The truth is that McKaiser, even prey to the vulgar pomposities of his delivery, is a crucial and valuable public voice, and condemning him prematurely might foreclose on engaging with what his work at least suggests: the possibility of a more rational, less idiotic South Africa. That McKaiser speaks at all on the issues he does is the first enabling gesture; that his perspective is often the alternative to the ossified public standard, is the second. But, as this review must surely have demonstrated by now, there are ambivalences and ambiguities in any possible appraisal of his work.

Let’s use his arguments on affirmative action as an example. McKaiser defends affirmative action from three challenges: that it’s racist; that it undermines non-racialism; and that it’s an insult to black people. Now, obviously, anti-affirmative action views that transmute a sociohistorical phenomenon like Apartheid into personal pathology (“natural ability and differences in work ethics”) are reductive and ahistorical, and McKaiser is swift to point this out. But in doing so, he’s only engaged a very simple-minded opposition. He leaves unattended the position that race is an insufficient proxy for affirmative action, and that more complex sociopolitical referents like class perform better. Then, further, when faced with the not-insignificant challenge that affirmative action produces psychic costs for its candidates (racialised stigmas etc.), McKaiser says: “The reason I am fine with being labeled an affirmative action candidate is because I understand the justice argument for why the policy exists.” He continues by saying that “being annoyed” at the label “affirmative action candidate” demonstrates a failure to grasp or to accept the justification for affirmative action in the first place. If you understand, accept, and internalise the reasons for affirmative action – the goals of substantive equality and justice – then you ought to not be embarrassed at being an affirmative action appointment or being perceived to be one.

But this solution appears to be the philosophic equivalent of a hearty “get over it”, and a position only possible for a self-secure middle-class intellectual to make. The racialised stigmas that gravitate around affirmative action appointees are produced through a network of social factors, and McKaiser has not in fact demonstrated that affirmative action does not produce this anxiety, but that if candidates accept the longue durée justice that affirmative action seeks to produce, that the psychic costs magically vanish in their felt intensity. These are two examples of the ways in which McKaiser’s confident-sounding arguments actually get to their terminus by either ignoring the more complex oppositions or prematurely concluding where there is a vaster, seething territory left unexplored. The problem is not that he is wrong, but that he is not attentive enough to the texture of the subject he engages.

There obviously isn’t enough time nor space here to rehearse his arguments in their fullness, and in some ways, it’s a bit hypocritical of me to deny McKaiser the rigour of reply that I criticise him for denying the counter-positions (or even positions sympathetic yet more complex) to his debates. But as suggestion to those interested, I would say that similar critiques of incompleteness or haste can be extended to the other domains of his combat.

In an article on the Brett Murray debacle, McKaiser takes the view that “Artists reflect back to us the world in which we live.” This is a very dangerous form of bullshit, because artists refract our world back to us, and the absence of any one-to-one symmetry in representation is what licenses the whole field of artistic critique. McKaiser then uses this over-reductive bromide to make blithe arguments about a lack of artistic education in South Africa, and art’s role in society (“The only normative requirement any artist should religiously stick to … is to produce works that are sincere"), ignoring the full gamut of 20th-century counter-positions to his well-meaning but naïve view. He leaves on the margins of his vision the really complex issues of race and power that more sophisticated critics have engaged, even while making the expected remarks about the value of satire etc. In an essay on animal rights, McKaiser makes some terribly anthropocentric arguments about the limits of empathy between humans and animals, so that he can license his conclusion that “a well-raised cow, treated decently, and slaughtered swiftly and humanely, is more than welcome to appear as ribs, wors or steak on my dinner plate. Yum yum!” His argument, which is truly laughable, deserves a full rejoinder elsewhere.

Finally, it’s quite difficult to recommend this book to anyone – one would imagine that the politically-illiterate fools that McKaiser takes aim against would be infuriated by his condescension; those who enjoy language would be bored by his cliché and gracelessness; liberal intellectuals would find his arguments simplistic and uninteresting; and general readers might find his arrogance and haughtiness quite distasteful. He doesn’t have the charisma of a Christopher Hitchens to pull off arrogance without coming across like a pretender. The issues raised in this book are all valuable and timely, but they require a more sophisticated champion than Eusebius McKaiser to really work.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project