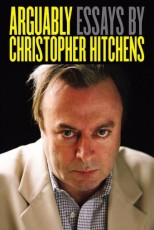

Arguably by Christopher Hitchens, Atlantic 2011.

Arguably completes the triptych: three volumes of pre-death nostalgia honouring the reportage and argument of Christopher Hitchens, the man Martin Amis called “the most terrifying rhetorician the world has ever known”. But after his death last month, the collection now has a touch of the funereal about it. The leftist obituaries have predictably veered between the irreverent and the venomous, perhaps withholding from him the same post-mortem decencies he denied Jerry Falwell (“give him an enema,” quoth Hitchens shortly after his death, “and you could bury him in a matchbox.”). The venom in these memorials centrifuge around a common criticism: the corporeal death is Hitch’s second; he had died intellectually a decade prior. These criticisms immediately hone on his apologism and denialism for the Iraq war, and his refusal to commit – like Žižek and others – to a full re-thinking through and rehabilitation of the Left. This collection both affirms and denies the breadth of these attacks. It collects essays which show the bankruptcy of Hitchens’s political perspectives (the absorption in Islam-hate and a self-aggrandising, violent Enlightenment register), but it also includes literary criticism and other oblique essays which demonstrate a throbbing intellectual pulse.

The collection makes sense as the last of a trilogy. The first, a memoir called Hitch-22, was written before his diagnosis with stage-four esophageal cancer. (And, as Hitchens darkly remarked, “there is no stage five.”) Yet it bore a consciousness of his twilight, its wide-angle focus tracking the historical divisions which took him from picketing car factories with Terry Eagleton to an alliance with the “war on terror”.

Earlier this year, The Quotable Hitchens compacted a selection of irreverent, iconoclastic lines. An example of such wit: “Reagan is doing to the country what he can no longer do to his wife.” At 788 pages (including acknowledgments and indices), Arguably is fleshier, possessing a greater depth of opinion. It collects essays written in the last decade or so (for the Atlantic, Slate and Vanity Fair, amongst others), a span of ten years which have proven to be the most combative and controversial of Hitchens’s career. This is the era in which he was called a “miserable sack of shit” by Alexander Cockburn; in which he accrued a fine list of leftist antagonists all accusing him – and certainly not without merit – of becoming a “neo-conservative”.

Earlier this year, The Quotable Hitchens compacted a selection of irreverent, iconoclastic lines. An example of such wit: “Reagan is doing to the country what he can no longer do to his wife.” At 788 pages (including acknowledgments and indices), Arguably is fleshier, possessing a greater depth of opinion. It collects essays written in the last decade or so (for the Atlantic, Slate and Vanity Fair, amongst others), a span of ten years which have proven to be the most combative and controversial of Hitchens’s career. This is the era in which he was called a “miserable sack of shit” by Alexander Cockburn; in which he accrued a fine list of leftist antagonists all accusing him – and certainly not without merit – of becoming a “neo-conservative”.

It’s here – seething in the prose – his remarkable, questing hatred of Islam. Much of Hitchens’s animation comes from his avowed anti-theism. He is most recognisable for his trenchant critique of religion in God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything. Since the late 1980s, though, he has held a special cerebral violence for the Qur’an. The homicidal fatwa against his close friend Salman Rushdie obviously offered no salve. 9/11 ended up producing strange rifts in the liberal consensus. Even Amis – another of Hitchens’s illustrious literary pals – was reduced to gurgling racist sentiment. “There’s a definite urge,” he wrote, “to say ‘the Muslim community will have to suffer until it gets its house in order’.” Amongst these proposed “sufferings” he suggested deportation, curtailment of freedoms and involuntary “strip-searching [of] people who look like they’re from the Middle East or from Pakistan”. He then proceeded to release a collection of essays – The Second Plane – offering up more frankly insightless scourging.

Hitchens follows the example of his hero George Orwell, who during the Second World War took aim at pacifists. Hitchens’s target is the Left, hunted down for their failure to support the Iraq war. (Incidentally, Hitchens has elsewhere written a monograph on Orwell, and the exemplary journalist is referenced over 35 times in Arguably.) He is explicit about the impulse which has broadly guided him during this century. After excoriating Mohammed Atta and the organisations which trained and produced terrorists like him (he is incuriously mute on the role of the United States in this production), he writes that “[p]ractically every word I have written, since 2001, has been explicitly or implicitly directed at refuting and defeating those hateful, nihilistic propositions, as well as those among us who try to explain them away”. This is really the space in which this whole collection might situate itself: the curious area in which a leftist intellectual like Hitchens can bring himself to (for example) capitulate to Enoch Powell. He says of the former, “[i]f he had stressed religion rather than race [in his famous denunciation of immigration into the UK], he might have been seen as prescient”. This characterises the divisions of the Left post 9/11: a split between, broadly speaking, the anti-totalitarian Left and the anti-imperialist Left. Hitchens admits he finds himself increasingly resolving any such conflict on the side of anti-totalitarianism. He nobly writes of his support for the “the forces who regard pluralism as a virtue”, marking them as “profoundly revolutionary”. He adds that “quite likely, over the long term, [they] make better anti-imperialists as well”.

A perfectly agreeable proposition, but one which is not borne out by Hitchens’s contributions to the Iraq war featured in this collection. In those moments, he reveals himself at his most dire: apologetic and self-wounding. Few would deny that his target – the “excuse making” of the Left, a certain tendency toward paralysis – was mere phantasm. Coupled however with his feverish anti-Islamicism, this engenders a series of pro-Iraq War, pro-Bush commentaries (although they are sometimes gloriously dispatched from the heart of the uncomfortable territories). It’s become too easy to malign Hitchens, and figures like Cockburn, Chomsky and Katha Pollitt have been equipped with numerous munitions by his vulnerable position. The territory is certainly quite complicated – glib dismissals of his position which have proven galvanic are missing the complexities that his contrarianism poses – but one must concede that America’s democracy via rifle approach is a self-defeating, contextually-unconscious gesture and Hitchens’s support comes up as inexcusable and trite. In a review of the 25th anniversary of Said’s Orientalism, he stages some representative criticisms: “[T]hat the military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq were wars ‘against’ either country is subject to debate” and “American Orientalism doesn’t seem all that restless from where I sit; it only asks that Afghans leave it alone”.

So Arguably seems to catch Hitch at a time when he was lurching a little too close to what he called his “temporary neo-con allies”. I have, however, been holding the fulsome superlatives in abeyance. If this collection shows Hitchens’s raging blindness on the Iraq issue, it also showcases his brilliance and genius everywhere else. His dexterous and agile use of language is the sovereign ambition of all writers. The breadth of his reference – and not an essay goes by without a rich intertextuality – is incredible. Such a skill before the blank page makes all his words eminently readable. His various arguments are compelling, critical and politically relevant. I could give an accurate measure of the range of subjects chronicled by saying they occupy all the territory between his self-subjection to the military practice of water-boarding captives (“Believe Me, It’s Torture”) to his sly tribute to the art and science of the blowjob (“As American as Apple Pie”). The former essay is one of his strongest set pieces. And then you have his restrained but stinging address to Amis’s Koba the Dread; the “most instantly misinterpreted of all his articles” in which he argues, using an odd mix of evolutionary biology and general bullshit, that women aren’t funny (but the conclusion is still rather compelling); in addition, there is attentive literary criticism which runs through Nabokov, Vidal, Marx, Wodehouse and Flaubert.

On a literary level, the essays are irresistible. His foreign correspondence (his “offshore accounts”) is alive with evocation and urgency, and with perceptive and breathing illustrations. And for all his being slagged off as a neo-con, Hitchens’s iconoclastic, democratic critiques sink into targets of all kinds. Sighted often with his teeth sunk into Islam, he still has vials of vitriol enough to take Christianity down; or the American judicial system; or North Korea, whom he loathsomely marks “a nation of racist dwarves”. Hitchens is committed to a now much-maligned Enlightenment project. It is, however a programme for universalism which withholds its munificence at strategic junctures: this produces a deep irony in Arguably. The bases of this project show themselves here everywhere in reasoned, lucid commentary; except in his detour into an occlusive pro-Iraq War stance: incongruent, almost phantasmagorically incorrect, especially when measured up against a mind given to such otherwise sharp opinions. This collection showcases Hitchens in all his charisma and vileness. It allows for fascinating study of a truly embattled figure.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

I don’t know. That he had to experience waterboarding before deciding that it was torture – what tosh. What a shallow ploy: look, I am courageous AND skeptical of the Bush regime, so I’m going to experience waterboarding (after all, I am a skeptic), before I pronounce on it. But I will pronounce on it.

For any sane person, a short description of waterboarding would decide the matter.

It’s not about Islamo-fascism and Islamo-that; the reasons for the invasion were fabrications (Hussein ultimately responsible for 9/11) and lies (Hussein had weapons of mass destruction, etc.) that Hitchens swallowed and then sold with pompous arrogance, using Islamo-fascism as his ruse while less eloquent people knew it was all a load of crock.

Kavish’s updated review – not the draft erroneously published earlier – is now up on the site.

Thanks Hedley, Hugh. Just a note: this review is the draft copy, not the final, in which I had more to say about the irreverent leftist obituaries in Hitchens’ wake. Unlike most, I am willing to give a lot more credit to Hitchens’ anti-Islamo-fascism stance. I think that there is something terribly more complex and complicit about his position than the way it was characterised by Eagleton, Cockburn et al. (which is not to say I’d absolve him of some of the more dire bullshit he had to say on the subject.)

I really liked Cockburn’s obituary: http://www.counterpunch.org/2011/12/16/farewell-to-c-h/ (everyone seems to agree that he tended to quest after the obvious (esp. his anti-theism) but did so eloquently. A jackass post-structuralist friend of mine recently dismissed him on this basis, but he was a galvanic force in getting people to re-think their cognitive mainframes, which is more than can be said for some academics)

I agree with much of Kavish Chetty’s review of Christopher Hitchens book. It is true that like many other Trotskyists (or former Trotskyists) he was more anti-totalitarian than anti-imperialist. In that context his position on the Iraq war can hardly be called ‘ragingly blind.’ He was fully conscious of the actually fascist (pro-Nazi because anti-Jewish) roots of the Iraqi (and Syrian) Baath parties in the second world war, and had first-hand experience of the appalling consequences for the Kurds (and the Shia and Marsh Arabs) of Saddam Hussein’s genocidal policies. Criticism of ‘Islamo-fascism’ should not be confused with anti-Islamism. It should also be borne in mind that Hitchens supported the intervention in Iraq, but his support was not unconditional or uncritical. He was extremely critical of the incompetent way in which the war was waged by Bush and Rumsfeldt. It should also be borne in mind that in spite of his Jewish roots (discovered late in his life), he was consistent in his opposition to Israeli policies, especially the settlements.

Thanks for this Kavish – some great nuggets. What mystified me most about Hitch was how such a great phrase-maker could ally himself with a neo-con-Dubya project that deployed bad language at every turn.

Must def track this down – I have his Unacknowledged Legislation: Writers in the Public Sphere, if you haven’t read it and want to swap…