Launch of The Loss Library and Other Unfinished Stories on 10 December 2011 at Boekehuis, Auckland Park

By LARA BUXBAUM

Ivan Vladislavić was in conversation with Michael Titlestad to launch his latest work, a collection of “unfinished stories”, at Boekehuis on Saturday.

For what was certainly the last event in the Saturday Voices/Saterdagstemme series of 2011 and most probably the final launch event ever, Boekehuis was packed to capacity. Several more people were huddled on the verandah, determined to ignore the ominous signs of an impending rainstorm. The mood was quite forlorn as no doubt everyone in the audience was aware of Boekehuis’s impending closure. I overheard at least two people mention that the gloomy weather was appropriate weather for a wake. However, if this was a wake, then it was a resolutely Irish one!

A packed Boekehuis

Corina van der Spoel welcomed everyone and expressed gratitude for the groundswell of support she had received since news of the imminent closure broke. She said she was both “moved and surprised by the reactions people have had ... how much they care for this place. In fact it gives me hope for books, for reading, for the possibility of doing something like this still in Johannesburg”. After a hearty round of applause, Van Der Spoel in her inimitable fashion said “I’m a bit worried it’s going to rain” and requested everyone inside the shop who had umbrellas to kindly pass them outside to those standing in the garden, should the storm begin. Vladislavić is certainly one of South Africa’s most prolific literary writers and Van Der Spoel displayed copies of Milnerton Market (a book of photographs by David Southwood, launched at the Book Lounge in Cape Town on the 9th of December) and Oblique (photographs by Abrie Fourie, published in Germany) both of which feature pieces by Vladislavić, as illustrations of his “very good publishing year”.

Titlestad, who is the head of the English Department at Wits University and also Vladislavić’s editor, began the conversation by briefly mentioning the “metaphorical coincidence” of discussing a collection entitled “The Loss Library” at Boekehuis. Although he informed the gathered audience that the launch was planned long before the “closure of Boekehuis was threatened and then pursued rather relentlessly by the holding company”, the poignancy of this coincidence remained undiminished. He expressed a desire to celebrate and acknowledge the “generosity of the space” that is Boekehuis, while simultaneously avoiding “being maudlin about the present situation”. There is some comfort to be found in the “loud and eloquent outcry about the closure”. It was in this spirit that the launch continued, both speakers making a concerted effort to avoid resorting to sentimentality, yet not denying their deep regret and sadness.

Titlestad’s impression of The Loss Library (and perhaps implicitly the loss of Boekehuis) was that it “speaks resonantly to the way in which certain processes and trajectories are interrupted, but we need to treat the interruption at some level, not only as a cause of despondency, but also as an opportunity. There are ways in which the ending of a particular story ... opens up occasions for new narratives, new possibilities”.

Prior to the conversation proper, Vladislavić read a moving tribute to Boekehuis he had prepared for the event. He spoke in elegiac tones about his long-standing relationship with Boekehuis: “My writing life has been bound up with the shop for nearly a decade ... This is the 10th time I have read here”. He celebrated Van Der Spoel’s astute literary sensibility: “Corina knows what you want to read before you do” and shared an anecdote about a group of “friends and colleagues” who have met informally on the “stoep” of the shop for the last six years, where “books eavesdrop on you and that gave the conversation a special savour”. He lamented the loss of Boekehuis and its “presiding spirit”, identifying this as a nadir and indicative of our failure to “value cultural treasures”. He concluded by urging everyone to sign the petition (available online at Bookslive.co.za) and hoped his tribute was “not too maudlin for Corina’s taste”. Vladislavić then read an extract from “The Cold Storage Club”, which relates his response to Bibliothek, the haunting memorial to the book burning which occurred in Nazi Germany in 1933.

Rather than posing direct questions, Titlestad structured the conversation around a series of observations about Vladislavić’s work. In what followed, the two engaged in a thoughtful and illuminating discussion about the nature of stories, the precise challenges of writing in the age of Google, the creative possibilities of incompletion, the archival impulse, the publishing industry and contemporary city life. It is always a treat to hear two such erudite, enthusiastic literary minds at work, engaging with each other with such apparent respect and delight. (See also the video on Slipnet of the launch of Double Negative.)

Concerning the potential creative possibilities of incompletion – as Titlestad glossed it, “rather than failure or resignation, incompletion becomes a site of revelation and possibility” – Vladislavić suggested that in addition to the possibilities it accords the writer, incompletion “also has great rewards for the reader”. He cited Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet [i] as a prime example of this kind of incompletion.

Titlestad observed that Vladislavić’s writing serves a necessary defamilarising function, “trading in the scraps of the possible and impossible. The Loss Library is the world’s most beautiful and fully formed scrapbook at some level”. To which Vladislavić responded, “Thank you. I think” and alluded to the influence of Geoff Dyer’s The Ongoing Moment on his writing. Vladislavić is clearly intrigued by the creative possibilities of the photographic medium as evinced by his recent collaborations with photographers. The Loss Library contains narrative snapshots of ideas, of hats, shoes, pathways, books and absences across time and geography.

Referring to the way in which fiction is capable of altering one’s relationship to the world one lives in, Titlestad celebrated Vladislavić’s “oblique vision of the world which casts it off kilter” and which has affected his own relationship to Jo’burg, to the details of the city he otices. At this point, Titlestad explained his quirky t-shirt choice for the launch, which was a fitting embodiment of his favourite line in Vladislavić’s 2004 work, The Exploded View: “I want to be a popular mechanic”. The appreciative laughter signalled that the melancholy mood had definitely lifted.

Citing a recurring interest in “writing and its possibilities” in Vladislavić’s oeuvre, Titlestad suggested that The Loss Library could be considered as a kind of “critical retrospective” or a “collection of things which cannot be written ... the negative image of what has already been written in a rich literary career”. In response, Vladislavić

admitted to being an obsessive “keeper of notebooks” or “an archive of failed fictions”. These notebooks act to “externalise the subconscious”. They “represent things you thought and had forgotten. There is a sense of a stranger who had versions of the ideas I now have”. Considering whether these unfinished stories should be returned to years later, Vladislavić claims “ideas and books have their moments. If you miss the train, you might not be able to get on it again. The next best thing is to write about the idea”.

At this point the questions from the audience arose. In response to the expression of a “severe sense of loss” in the city, Vladislavić acknowledged the positive “transformation of Jo’burg”, although he confessed to feeling keenly the narrowing of “certain lifestyle possibilities” and the “loss of public space”. Asked whether his recent work signalled a structural departure in his writing, Vladislavić, although reluctant to act as his own literary critic, suggested that The Loss Library exists in a state of “completed incompletion”. Portrait with Keys, on the other hand, is “full of absences and gaps”. In a self-reflective mood, Vladislavić continued: “[The Loss Library] looks a little bit like a plan for a book ... Or a template for something, but what?” Regarding his overseas reception, Vladislavić revealed that, although he is popular and well translated in some places, notably in Germany and France, the absence of a “regular publisher in the UK and USA is a stumbling block” to developing “an international name”. Considering this state of affairs further, he contended that the international audience for “literary writing” in general is decreasing. With characteristic self-deprecating humour and humility, he added a coda: “but I might just be making myself feel better”.

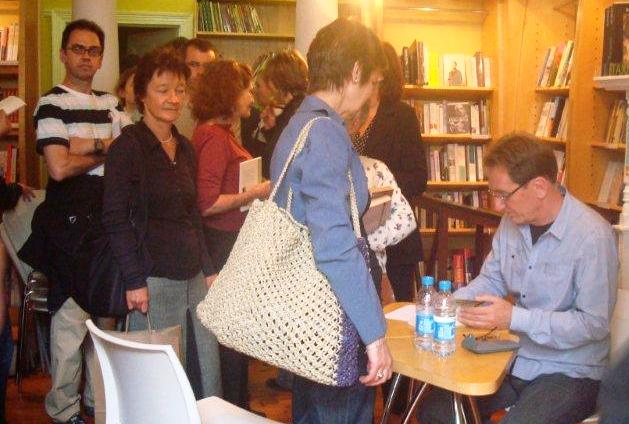

People queuing for autographed copies of Vladislavić's new book

On that note, the discussion was dissolved and people started queuing to have their book signed, to buy books while they still could, to take advantage of the spread of delicious snacks and wine and bask in the sunshine peeking through the clouds, after the storm that never arrived.

Georges Perec [ii] (who Vladislavic refers to as an influence in the ‘story’ “Gross”) contemplates what it might mean to “cultivate” a “neighbourhood life” and whether buying goods from the same place every day, exchanging curt greetings with sellers as money changes hands would be sufficient:

... but that would only be putting a mawkish face on necessity, a way of dressing up commercialism. Obviously, you could start an orchestra, or put on street theatre. Bring the neighbourhood alive as they say. Weld the people of a street or a group of streets together by making something more than a mere connivance: by making demands on them, making them fight. (58)

Although a space in which books are sold, Boekehuis has never been about mere commercialism, as many of the letters protesting its demise have eloquently expressed. Boekehuis has indeed, in a meaningful and not easily dismissible way, brought the city alive. As Titlestad expressed in his introduction, perhaps one of the legacies of Boekeuis is that it has made and will make the denizens of Jozi fight for the endurance of literature and for a safe space for the exchange of ideas.

Although the space may be lost, perhaps it is wrong to think of Boekehuis as akin to a lost library, as the books of Boekehuis (identified by their idiosyncratic and meticulous handwritten prices and dates of acquisition on the label) are sure to be found in private libraries around the world, as a kind of enduring testament to the beautiful books sourced and sold by Corina van der Spoel and her staff for twelve years at Boekehuis.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project