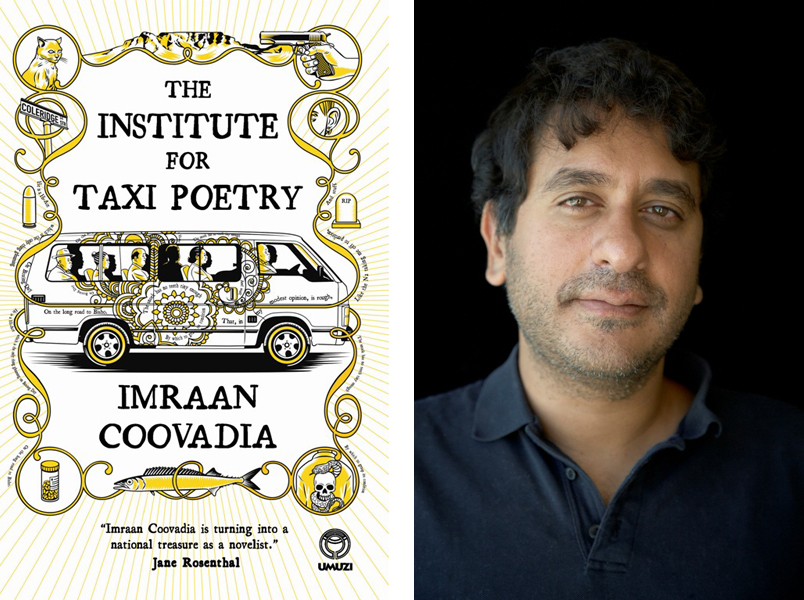

Launch of The Institute for Taxi Poetry by Imraan Coovadia, 17 April 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

KAVISH CHETTY

“It is a rare gift to be seriously funny and seriously serious,” Mervyn Sloman remarks. The accomplishment is that of Imraan Coovadia, speaking about his new novel – The Institute for Taxi Poetry. He speaks to a well-thronged upper floor of recognisable reporters and scholars – most of whom have made the migration upstairs after double-dipping braised-potato spring rolls in the sweet chilli sauce (I saw you buddy – the tweed and suede doesn’t fool me). His interlocutor is journalist-at-large, O’ Toole, of the Sean variety. The event is casual and conversational, buoyed by Imraan’s disaffected charisma and Sean’s researched and imaginative questioning style.

“Last year Imraan interviewed me,” begins Sean, “and his first question floored me.” He had to stare blankly into the audience, eventually dredging up an answer that leads him to say, “I have hated him ever since.” There are gentle murmurs of laughter, and a relaxed atmosphere that avoids the dire and machinic question-and-answer routine (with its hanging epochs of silence) which weary the lesser launches.

Sean begins by remarking on a photograph of Imraan “ferreted” from Google Images, which features the latter in a composed shot taken during his residency in Italy, 2009. He sits before an old IBM laptop. “I always figured you for a Dell kind of guy,” says Sean, “or maybe a beat-up Apple.” “Well,” replies Coovadia, the tilt of head and comic timbre of engaging the question with such mock-introspective seriousness has the audience in shattered

Imraan Coovadia

laughter. “Most of my things in life are hand-me-downs from my father, like my political ideology; and most of my shirts and jackets.”

Coovadia’s new novel – featuring murder, comedy and interrogation – is about narrator Adam Ravens and his questing after (friend and fellow taxi-poet) Solly Greenfield’s curious demise. Adam Ravens begins his career as a “sliding-door man”. This is the more orderly, bourgeois cipher for what in Cape Town argot is the curdled gaatchi. I’ll forgive Coovadia for the stylistic occlusion, because while he reckons “sliding-door man” is parlance up north in Jo’burg, we can keep it real and admit that gaatchi sounds like a descriptor for that thrilled rush of heat up the oesophagus – usually felt in bulimic post-pizza vomit-pageantry.

Adam “graduates” from this gig to become a taxi-poet, scribbling stanzas on the bodies of the commuter vehicles, and later “graduates” again to become an academic, much like Coovadia himself, who is our loveable sloven at UCT’s English department.

The book, it is whispered more than once in the Book Lounge basement, is a satire which veils that department’s relationships. Reading it could become a sleuthing game of gossipy guess-who – which is always fun because literary scholars, whose careers are filled with words like “catachresis” and “palimpsest”, seek out the greater portion of their equilibrium in casual harassment.

To slyly confirm these ciphered biographies, Coovadia quotes poet Kate Kilalea – who, incidentally, once wrote a poem called “The way we look is a game of chess”, which made me laugh so hard I almost ruptured my innards (I admit with dry melancholy, that was hardly the intention of the piece). He says “She quoted a guy called Gilles Deleuze” who spoke of “the productivity of the secret”. Coovadia continues “In fiction, a lot of [that] secret is the author’s own life or experiences. That secret becomes productive because it is constantly invaded, but also introduced all the time through a book. There is something about the fictional method that does that, and it’s very powerful.”

When prompted on writing method: Coovadia says, “You feel like you have to go away and live in a castle for six weeks with people you know are going to drive you crazy. I was sharing a large palace [during his Italian residency] with an avant-garde French jazz composer called Benoir. I knew he was going to drive me crazy, and he did. By the end of the first day, I knew more about his three ex-wives," and also, Coovadia adds, the dividends they were scoring from his bank account.

Coovadia started the book in 2009 as a project of distraction. When Sean mentions that an earlier draft of the book featured the word “ahistorical”, culled from the final version, Coovadia says he approaches writing like a “random thinker”, and that “the process of editing lets me get rid of all the random thought I put into my story. Any idiot can tell you that the word “ahistorical” should never appear in a novel. The interesting thing is that I was awkward enough to use it in the first place.”

Coovadia lacks the requisite credentials of a working-class background that is pretty much de rigueur in today’s voguishly anticapitalist literary circles. He’s also never been on a taxi, and interviewed a splendid total of one taxi lord as part of the book’s research. So, why did he write it?

“I’m the worst possible person to write this book, except for all the other people who didn’t write it,” he says. “I kept thinking why no one else has written about it. Taxis are obviously such a South African form.” He acknowledges that taxis feature in other African states, but adds that they lack the “taxi associations” and “soviet systems of authority” and “long, bitter assassination battles” which mark our own. He encouraged another dude to write a non-fiction work about taxi culture in South Africa, but the dude in question was promised a swift killing by the approached taxi drivers. Project suspended.

The novel is “invented”, then, says Coovadia. “What is an invented poem?” he asks. “It is invented out of a problem that all contemporary South African writers have. I’ve been really interested in this phrase of Kentridge’s [although I have a suspicion it was Loren Kruger who used the phrase] – it’s not that we’re a post-apartheid society, but rather a post-anti-apartheid society. We all have these progressive and revolutionary traditions that we feel at some level attached to, but we don’t know what to make of them. This book is an imaginative attempt to think about how we could use or fantasise about those [revolutionary traditions].”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Benoir? I would have thought it would be Benoit, or Benoist (Benedict). “Benoir” has another meaning that I’m not sure is even safe to reproduce here for fear of flagging (Urban Dictionary outifts one, though). Unless of course it was this _ahistorical_ ‘benoir’ that drove Imraan “crazy” during his stay at that palazzo? (*shudderz*)

Nice write-up. The launch was fun. O’Toole’s irreverent approach was as refreshing and eye-opening as the acidic scald of the sponsored wine etc etc (thankfully, his pairing with Imraan was some form of malolactic reparation).

However there are still some inequities – a character named ‘Solly’ is almost unforgivably vinegary. I suspect some sort of local genre parody is going on here but I can’t be sure without reading more.