Report on Poetry night with Breyten Breytenbach, Rustum Kozain and Oswald Mtshali

Session 3 of the M&G Literary Festival: Thursday August 30, 7pm, Market Theatre

LARA BUXBAUM

Thursday night, Newtown, Johannesburg, and I find myself carried along in a sea of people into the main theatre at the Market for an eagerly awaited poetry evening at the third annual Mail & Guardian literary festival. A rare gathering of talent – the poets Breyten Breytenbach, Rustum Kozain and Oswald Mtshali – were hosted on stage by festival co-director Corina van der Spoel and Georges Lory, director of the Alliance Française Johannesburg. It was an event which couldn’t quite decide if it was a poetry reading or interview, but quickly found its rhythm as questions were answered with poetic monologues and/or poems.

Van der Spoel introduced Oswald Mtshali, whose classic collection Sounds of a Cowhide Drum (1971) is being republished in English and Zulu by Jacana. Mtshali quoted approvingly Shelley’s dictum that “poets are the [unacknowledged] legislators of the world” and bewailed the tragedy at Marikana. In response, he read his prescient poem, “A Miner”, inspired by the Coalbrook mine disaster and a second poem evoking the emotions experienced by migrant mine workers (“amaguduga”) travelling on the train.

Referring to Nadine Gordimer’s description of Mtshali as having a “city poet’s tongue”, Van der Spoel asked him to reflect on the changes he had witnessed in Soweto in the course of his lifetime. Mtshali, who grew up in “Shantytown”, alluded to the political prevarication that sees “slums elevated to informal settlements”. But he also praised the enduring communal spirit of the place.

Mtshali then read “This Kid is no Goat” and “A Newly-Born Calf”. In answer to a question about the relevance of traditional poetry, Mtshali argued for “the need to stick to customs and tradition and not to forget” and then, as if for emphasis, read a rousing rendition of the title poem of his collection. “Boom Boom Boom”, it echoed through the theatre, the audience rapt as Mtshali conjured the drum to life, his voice incantatory, his foot tap-tapping out the beat.

Corina van der Spoel interviews (from left) Rustum Kozain, Breyten Breytenbach, and Oswald Mtshali

Lory, who translated Breytenbach’s poems into French, commented on the “strange challenge” entailed in introducing Breytenbach to a South African audience. He referred to him as a “migrant poet”, alluding to his itinerant lifestyle, to which Breytenbach interjected “migrant labourer” and Mtshali proposed instead “iguduga”, recalling his earlier poem.

Lory’s opening gambit was to ask Breytenbach, who was awarded the Mahmoud Darwish Award for Creativity in 2010, to talk about his friendship with the late Palestinian poet.

The first thing Breytenbach did was to dedicate his contribution on the night to the late Neville Alexander, reading a short elegiac fragment from his notebook which began, “it is always too late when it comes to this”.

Breytenbach segued from Alexander into a reverie of Darwish and related one of his “most powerful experiences” – hearing Darwish read in Ramallah. Breytenbach insisted that both Alexander and Darwish’s lives should not be “instrumentalised or appropriated” for causes, as is the tendency, and that we should “refuse to simplify”. He then read from his collection “Voice Over: A Nomadic Conversation with Mahmoud Darwish”, describing the poems as “sometimes renderings of [Darwish] poems” which tried to “fit into [Darwish’s] slipstream”. Poem “number six” contains the haunting refrain “we shall be a people”:

We shall be a people once we forget the dictates

of the tribe so the citizen on his knees may enter

the private kingdom of everyday lovemaking life …

For we shall be a people, oh my people, when we recognise

the exact beat of life's passion and death’s urge

In a second round of questions, Lory asked Breytenbach about the flexibility of Afrikaans, and the possibilities of “twisting the language”. Pre-empting or perhaps giving a glimpse of the conversation he is scheduled to have with Patrick Chamoiseau on Saturday, Breytenbach referred to Afrikaans as a “creole language”. He read an elegy in Afrikaans by “Jan Blom” – mischievously stating “not me, but I’m reading it anyway” – for his publisher Daantjie Saayman. And in his hypnotic enunciation, the materiality and innovative possibilities of Afrikaans were clearly illustrated.

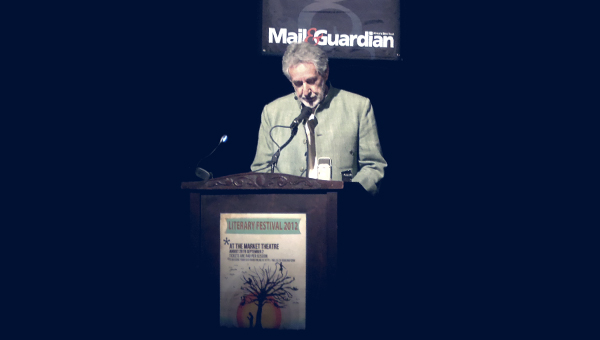

Breyten Breytenbach reads his poetry in a rare stage appearance at the Mail & Guardian Literary Festival

Rustum Kozain declared it an “honour to read with elders whose poems [he] read as a teenager”. But in response to Van der Spoel’s request that he discuss the importance of the Cape in his poems, Kozain begged to “go against the grain”, preferring to read his poems than talk about them – to loud applause.

Kozain read four poems from Groundwork – timed, he assured us, to last no more than ten minutes, although the audience would clearly have loved an encore. Kozain recited “Regret”, “This is the Sea” (based on a photograph by Victor Dlamini), and two longer poems. “Kingdom of Rain II” expresses the desire for a different kind of interaction with another – an encounter with a grizzly bear in which he is “not hunter nor prey”, invoking the bear to “look at me here outside of history”. As a conclusion, he read an extract from an unfinished poem called “Memory”, which in its narrative trajectory considers the private pain of a first heartbreak alongside more public trauma, the public and private inextricably, viscerally bound together: “that cut below the heart, that one that never heals ... lasts as long as a word like slave survives” and continuing to “a public hurt, apartheid hurt us beyond the wheel of reparations … and so we carry on hurting”.

Rustum Kozain reads from his recently published collection of poems, Groundwork

The floor was then opened to the audience. Victor Dlamini inquired about the courage involved in pursuing poetry – or, to quote Greg Brown, “playing the poet’s game” – in a context where much that is deemed “difficult” is dismissed.

An animated interchange among the poets ensued. Kozain admitted it’s “depressing” and Breytenbach quoted Elisabeth Eybers: “[Y]ou have to be ill and healthy enough to write poetry”. He described poetry as “another language”, an attempt to “placate the unknown”.

Mtshali, who had disappeared from the stage, returned bearing a bible, and provided his own elliptical answer by reciting Job: 28 about wisdom, its mining imagery drawing the conversation full circle.

On the issue of translation, Mtshali explained that he writes in English and Zulu, “trying to bridge the gap … to bring us together”. Kozain humorously recalled trying to translate T.S. Eliot as an undergraduate: Prufrock’s “tea and cakes and ices” might have been “tea and koeksisters”, before emphasising the necessity of translation, without “problematising it”. Kozain firmly corrected the misperception, raised in another question, that protest in poetry had “stood still” since 1994. He insisted that in fact poetry “is the only place in South African literature where people are explicitly criticising government”.

Oswald Mtshali, ever casual, remains seated as he reads from his famous collection, Sounds of a Cowhide Drum, which is being republished in English and isiZulu by Jacana

Mtshali cited Ingrid Jonker’s “Die Kind” as one of the most enduring protest poems ever. Breytenbach agreed, suggesting you could translate “pass as boarding pass these days”. He continued “there are obviously praise poets or official poets who praise the pigs at the trough, but that’s not what poetry is about”.

With a final flourish, Mtshali displayed his copy of an old issue of the “Purple Renoster” literary journal from 1968, in which his poetry appeared for the first time ever in print. And following the rousing applause, the sea of bodies flowed out of the theatre, to buy poetry books at the Love Books stand.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project