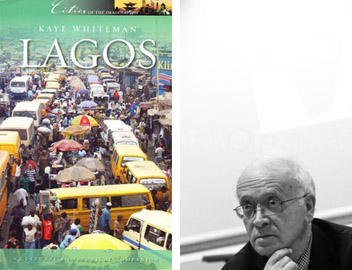

Lagos: A Cultural and Historical Companion by Kaye Whiteman, Signal Books, Oxford, 2012

Writing of the country in general, the publisher of Lizzie Williams’ (excellent) Bradt Travel Guide Nigeria says that there “you will find nothing but kindness and hospitality.” That is a bit of a stretch, but the point is well made: not to underestimate the vast positive energies of a country many people, including Africans, would quite happily never set foot in as long as they live.

The foul reputation Nigeria suffers is only magnified when it comes to its largest, and former capital city, Lagos. Williams acknowledges just how horrible this place can be: witness her comment that there is a YWCA [Young Women’s Christian Association] hostel in Lagos, but “as there is absolutely no way I am going to encourage even the most hard-nosed female traveler to stay there, I am not even going to tell you where it is.” And yet, as Kaye Whiteman makes the essential point in his preamble to his book Lagos: “a city that has all too often been portrayed to the outside world as being a hell-hole of crazy slums, endless traffic jams, con-men and chaos . . . is so much, much more.”

One of the most highly respected journalists writing on Africa and a man of huge experience (Lagos has a photo of his witnessing the signing of the treaty that concluded the Nigerian Civil War), this is, surprisingly, Whiteman’s first book. Also surprisingly, it is the first of (to date) some 40-odd volumes in the series “Cities of the Imagination” to cover a metropolis in sub-Saharan Africa (when do we get volumes on Joburg, Cape Town, Addis, Dar?)

While mindful of the ethical responsibility not to understate the depth of misery most Lagosians undergo in their daily lives, Whiteman states that central to his book is “the impact that the genius of the city and its astonishing melting-pot has had on the creative output of its people” – hence at the core of the book are its chapters on literature, music and the general creative environment.

Before this Whiteman gives an account of the founding of the city – remarkably lucid, given the complexity of, and inconsistencies within, the oral record and early published accounts. The city comes into focus at the end of the 18th century as trade, and especially the slave trade, flourish. There follows the British takeover, the first stage driven by a powerful nexus of forces: the increasing demand for palm oil; the utilitarian notion of benefiting through good deeds (i.e. missionary work); the unrivalled might of the British navy; and the impulsive, indeed incendiary, temperament of Foreign Secretary, later Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, who might be regarded as the godfather of modern Lagos. The bombardment takes place in 1851; the Treaty of Session ten years later – a document so craven that Whiteman reproduces it is an Appendix. Encouraged by the British, the Saros (Sierra Leoneans) arrive, providing a community of assistants to both missionaries and the colonial administration. This is prelude to a period characterised by what Whiteman calls “the growing gene pool”, and lays the foundation for the perennial question “who are the Lagosians?” Whiteman gives a concise account of a complex history that has been bedeviled by loose group naming practices: “Hausa” becomes coterminous with “northerner” and even “soldier”.

At the end of the 19th century what is now Nigeria begins to emerge “through a ruthless mix of conquest and purported treaties”, giving Lagos a vast hinterland just as it was on the point of “making a great heave to be able to serve it”. We enter the modern period: the expansion of healthcare; the introduction of the railway and a massive programme of land reclamation; and the growth of the public sphere, of political debate and (still visible) a vibrant newspaper industry. The continuous repopulation of the city continues, and Whiteman notes that post-apartheid South Africa does good business in Lagos – as an aside, he recalls “a certain Wayne who had been in the apartheid regime’s special services in Angola, and was hating every minute of Nigeria”.

With the foundational work done, Whiteman’s book moves on to a succession of chapters on specific topics: first, on the city’s topography, focusing on the relationship between island and mainland: “the strange way in which Lagos is laid out in a tangled dichotomy between land and water is an essential part of its soul” – stranger, indeed, even than Cape Town. Then comes a chapter on the “look” of the city, closely tied to its turbulent history of social formation. Remnants of the past are lovingly described, such as the Shitta-Bey mosque, “an astonishing example of Brazilian architecture adapted to the service of Islam”, but Whiteman is nothing if not attuned to the energies of the present. These are frequently anarchic: with the growth of air traffic, “Nigerians have become amongst the most inveterate air travelers in the world, acquiring the reputation of having more baggage than any others”. (Indeed: I have witnessed among cabin-luggage on flights to Lagos a Christmas tree and a lawnmower).

There is an extensive, very well-informed chapter on Lagos literature, and as one of its epigraphs reminds us: “Lagos has, by the early years of the 21st century, become established as one of the world’s pre-eminent fictionalised cities.” Whiteman notes that key to the work of Lagos writers is “a brooding spirit of cantankerous defiance that often infuriated the colonial rulers” – and, one might add, their successors – “who recoiled in horror and distaste and often made the most terrible utterances about the inhabitants that can now be worn as a true badge of honour.”

A chapter on music, film and art (also very good) features a photo of the masked saxophonist Lagbaja (“Nobody”) and memories of clubs such as Tiberius and WhyNot?, and of Gloria belting out numbers such as the immortal “If you marry taxi driver, I don’t care” (rumoured to have been created as an improvisation by Wole Soyinka).

The final chapters include one on seminal episodes in the city’s history – a neat way of covering vibrant topics in mini-essays that would have impeded the flow of the earlier part of the book. The great musician Fela Kuti (“archetypal Lagos boy”) gets a chapter to himself, as does the notorious FESTAC festival of 1977 – in Soyinka’s words “a vulgar, unprincipled and directionless jamboree in a nation where petroleum crude had turned the brain into human crude” – although Whiteman is considerably more forgiving, seeing FESTAC as “a profound existential experience that confirmed the extraordinary and unexpected nature of Lagos.” These chapters also allow Whiteman enough elasticity to include personal anecdotage; this is of such good value, he must be leant upon to produce a book of memoirs. To end, Whiteman has a chapter titled “The Future City?”, which begins with a quotation from the present (and dynamic) city Governor, Babatunde Fashola: “If we can change this place, everywhere else will change.”

Although Lagos is extremely well-written, some may feel that, in places, it labours under an over-massing of detail. But it is a remarkable labour of love, and both a gripping read and a valuable reference work. The book has a large number of very fine photos; the one used for the cover gives a hint (though no more) of what Lagos the hell-hole looks like. There are also drawings of historic buildings by Nicki Averill. If this review prompts just one South African to read Whiteman’s book and to visit a city I have come to love (and, yes, loathe), I shall feel I’ve done a good job. As Lizzie Williams puts it: “Love it or hate it, Lagos has to be seen to be believed.”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project