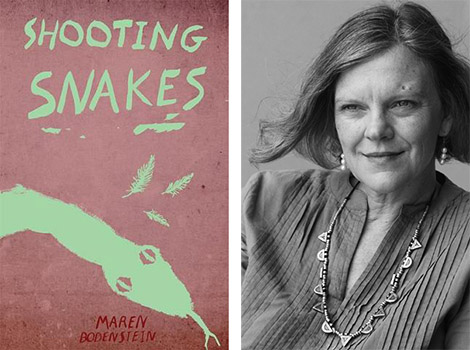

Shooting Snakes by Maren Bodenstein, Modjaji Books, 2013.

A review can come about through serendipity. While I was staying with a dear friend last December, she proferred me Bodenstein’s novel with a tentative “you might try this”. I was reading in tandem books by Imre Kertesz and Jose Saramago and at first glance the prospect of Shooting Snakes seemed less than thrilling. Once I began, though, I started notching up the superlatives: gripping, shocking, utterly beautiful. After Shooting Snakes I lapped up Bodenstein’s children’s story Mafia and the Aeroplane (published under the pseudonym Max Sed, by Human and Rousseau) and, while Kertesz and Saramago lay neglected on a far corner of the sofa, I moved on to another children’s story, Mafangambiti: The Story of a Bull, by the Venda writer T.N. Maumela, a work that is so very good I’m trying to organise a translation into Sesotho.

So what’s with the Bodenstein?

In this story of three generations, first we see Johannes, an elderly widower, kept awake by the chanting of a Venda prophetess. He’s afraid she will accidentally set fire to the bush around his farmhouse and he’s also afraid of the snakes he is sure must be thriving in the basement (“beneath him the slithering mass hiding from the heat”). Then Johannes’s first person narration takes over, with him as a child on the Lutheran mission station where his father works. It is shortly before World War Two and, as a German national the father is about to be interned (he is sure this will not be for long, as Germany is bound to win). Bodenstein’s prose, lucid and responsive, maps out the tender but tetchy relationships between Johannes and his siblings and their friends, the children of the mission’s VhaVenda staff.

Past and present narratives alternate. Johannes’s environmentalist daughter, Susanna, arrives for a visit, still reeling from having lost her temper at a conference “with those post-colonial pricks from the First World countries, who thought they knew everything.” (One minor disappointment with the novel is that we don’t learn much more about this or its aftermath). The relationship between Susanna and Johannes is fraught, the latter humiliated at how far he has let his life go to seed since his wife’s death, the former placing him under a regime of surveillance and “retail therapy.”

Johannes’s childhood narrative begins to establish the social hierarchy under which he grew up: on a picnic he and his siblings aren’t to bathe naked, since, as their mother insists, they are not native children. They respond by etching ribbons in the sand with their pee. There is, too, enchantment: on the mission station, a treehouse, and a holumbe, a cross between a rabbit and a large soap bubble, which teases the children by changing colour, sticking out its tongue, and farting. (Every garden should have one). And there is, of course, also darkness: when Missionary Bester contracts smallpox, Evangelist Petros subs his sores with ointment; but as Johannes’s father points out, this is just about the best way to pass on smallpox, and both men die. With VhaVenda friends, Johannes debates different repertoires of experience, especially the do’s and don’ts (mostly the latter) that their respective parents prescribe. Nothing escapes his bright eye and attentive ear: the world of the mission, world within world, is brilliantly captured.

As the narrative becomes more threatening, the children’s mother tells them they cannot go to the mission school, because that is for Africans. This disappointment is offset by the news that the queen of the Lovedu, a “real rain queen”, is in the vicinity. Meanwhile the kids play at throwing bombs on London – and on Johannesburg, “because South Africa is part of Britain.” Here Bodenstein is able to accomplish so much with so little.

When Johannes complains that she understands neither him nor his work, Susanna turns on him and protests: “Of course I understand farming, Dad. It’s all about high yields and fuck the rest, isn’t it? Fuck the water table! Fuck the soil! And fuck the planet while we’re at it.” Johannes’s only reaction – not exactly self-reflective – is to wonder where she learnt to swear,

She reminds him that she and her mother used to hate it when he came home (“All that misery you brought into the house”) and, responding, Johannes confuses his wife’s name with that of his sister, Susanna’s Aunt Anna. Over the next few chapters Bodenstein fills in Anna’s story, another nail in the coffin of this most unhappy of families (and yes, it is, very much, unhappy in its own way). In another very deft touch, Bodenstein adds edge to the mounting tension through an episode in the local dorp in which Susanna is nearly mugged by a young black whose combination of nastiness and assurance in his own sexual allure are skillfully depicted.

Shooting Snakes is saturated with yearning, with the need, to paraphrase H.G. Wells, to bridge the gulf between what was and what is. It is a stratified novel, one that uncovers layer after layer of loss: the historical dispossession of the VhaVenda, the rents in Johannes’s family, the near-breakdown state of Susanna. When at the end the holumbe is seen again, the effect is heart-wrenching.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project