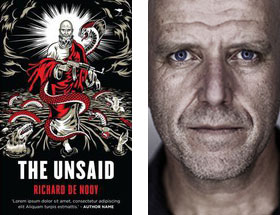

The Unsaid by Richard de Nooy, Jacana, 2014.

Close to the end of Richard de Nooy’s compulsively readable conclusion to a loose trilogy that includes Six Fang Marks and a Tetanus Shot (2008) and The Big Stick (2011), we are told that “all beauty and truth are born of suffering”. While such an affirmation of the need for suffering to produce that which is beautiful and truthful has been widely accepted throughout the ages, the aphorism in question takes on a particular kind of ethical significance in relation to the central binding figure in all of De Nooy’s fiction to date: the journalist JR Deo, in The Unsaid ordered by the courts to undergo psychiatric evaluation by a certain Dr Hauptfleisch (literally translated as “Dr Headmeat”) in what we come to know as the Forensic Observatory. Deo is to be tested in various ways for his accountability in an attack on a group of men in a bar one fateful evening. The resonances the novel has with the real-life turn of events that has seen Oscar Pistorius ordered to visit the Weskoppies Psychiatric facility in Pretoria are both timely and fascinating. For reasons I am about to disclose, De Nooy’s The Unsaid is one of 2014’s most memorable, creative works of fiction thus far, one that demands an attentive and intelligent audience.

In a particularly dense yet accessible narrative of only 190 pages, De Nooy confronts the reader, who is often addressed directly by the unreliable narrator Deo, with a carefully regulated flow of fragments and marginalia: bits and pieces of letters, reports, psychological evaluations, conversations between a motley crew of inmates, intimate reflections on mortality, responsibility, ethical reporting, physical, spiritual, emotional and discursive forms of violence and degradation, the psycho-geographies of power and the antinomies of authority, and the meaning and content of what it takes to be an ethical human being with genuine empathy for the other. A tall order, then, by any writer’s standards.

Yet, there is so much more: while Deo becomes accustomed to days and nights spent in a highly regulated, almost mechanical, colourless environment, where women are almost entirely absent, he must come to terms with the death of his parents, the dissolution of his marriage, the loss of his wife and children after his divorce, and the loss of his best friend and long-time companion in the field of war reporting, Mad Mick. With an arresting feel for atmosphere, nuance, light and shade, De Nooy is able to portray a deeply wounded, traumatised soul with such pathos and power that one is held captive long after the novel’s final pages. This is a man whose life is described by his brother in the novel’s opening (a revealing, painfully direct letter) as a “cesspit”, an “open sewer”, an expression of “relentless experiments and reckless pursuits” that centre on “lab rats who died in his wake”.

De Nooy’s uncanny ability to create memorable, three-dimensional male characters extends from Deo – whose name and character give rise to readings that range from the divine to the (self)destructive, from projections by others of their own fears and desires to archaeological digging into his past traumas and moments of suffering – to what is arguably the novel’s most audacious and successful conceit: by Deo’s hand, a variety of deceased men, invariably “Bad Men”, repeatedly invoked as those “wolves” that would hunt and feast on Red Riding Hood, are brought back to life to voice their own stories. As opposed to the more general trend of writers making an attempt to speak for the dead that have suffered a multitude of physical and psychic injuries before their death, often under conditions of war, oppression and tyranny, The Unsaid turns this form of commemoration on its head.

What we are confronted with as readers is a succession of stories from the perpetrator’s perspective – while no excuses are ever made for many terrible, terrible acts committed by these men, De Nooy employs a daringly direct, seemingly unmediated style of reporting the crimes and actions, placing them in broader context and making the reader complicit as a willing participant in this dialogue. In these unequivocally harrowing stories that range in name from “Nazgul” to “Samaritan”, a cornucopia of complicities both troubling and affecting emerge. Invariably, the reading of these uncompromising narratives are the equivalent of being held underwater, only just being allowed to breathe before it is too late.

If The Unsaid is about coming to terms with the fact that madness and folly are but outliers on a continuum that stretches towards an antithetical righteousness, sensitivity and courageousness in daring to oppose that which is unjust in society, the novel is surprisingly accessible, written with a perceptible lightness and deftness of touch. Whether it is the constant references to the protagonist’s scatological powerlessness (he is thoroughly constipated throughout); moments of comic genius such as a reference to the trio of Cash, Waits and Springsteen as the “howly trinity”; or the fact that the orderlies continue to say “baie dankie” to him at the close of each brief and banal conversation on the subject of his preferred fruit, De Nooy achieves a rare balance between cutting humour and humane treatment of his cast of oddball characters. I found the novel absolutely hysterical in several places, consistently attuned to the paradox of warm-hearted humour amid a setting that brings to the forefront increasing occasions of absurdity, surrealism, farcicality and irrationality.

The final quarter of the novel sees a feverish increase in pace, and the Deo we have come to see and have a measure of understanding for is revealed in a potentially new light. Some readers might find this revelation and shift in tone rather jarring, although others would see the direction De Nooy chooses for Deo as one that is essentially true to his character. As the novel carefully plays its hand in revealing (or not revealing) the way things end for Deo, the reader is left with much food for thought, akin to the similarly stimulating denouement of The Big Stick, where the reader (and Deo) must deal with the tragic death of a beloved son, Staal, from a conservative Afrikaner household.

After re-reading the novel, I can only but marvel at the ways that the tragic, the comical and the catastrophic are combined in almost equal measure to produce something genuinely engaging and heart-wrenching, rightly compared to Ken Kesey’s triumph One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Christopher Hudson’s The Killing Fields. Both books of course also have corresponding cinematic equivalents, and The Unsaid is nothing if not visual and cinematic in its storytelling. At various intervals, I thought to myself that The Unsaid channelled some of the energies and formal or thematic concerns of great and diverse works of literature: Crime and Punishment, A Clockwork Orange, A Million Little Pieces, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Fugitive Pieces, A Harvest of Thorns, Country of my Skull, The Bang-Bang Club. As the elegiac final instalment of the J.R Deo trilogy, The Unsaid certainly makes its mark, and deserves to be read and admired.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project