Jitsvinger -- Photos: Retha Ferguson

BY KATE ELLIS-COLE

Dearly beloved, this past Sunday morning I made a tweet, complaining that I needed to be rescued from my thought world and get in touch with reality. Adrian Different, patron saint of all things InZync, responded with a: “Well, why not let InZync save you?”

He had no idea how prophetic his words really were.

Stepping into AmaZink on a rainy Sunday is somehow reverent. The denser setup, with no tables, and rows of chairs lined up like pews, did give the venue an oddly parochial feel. But there is nothing quiet or reserved about this parish. Its congregation begins to fill the space as Diff announces that it’s time to begin; and every denomination of beauty and belief is evident in the assemblage.

On Sunday the 2 March, InZync played host to a British poetry group who go by the name Tongue-Fu. Brought to our shores by the British Council Connect ZA, Tongue-Fu is the brainchild of Chris Redmond, who also organises the events. Chris is the first to take the mic as he introduces the dynamic of Tongue-Fu, describes for us the risk the poets are taking, and the procedure involved in each performance. Essentially, what is going to happen is that each performer will identify a style or particular beat that they want to perform to, and the band improvises.

Chris Redmond

The band, made up of Arthur Lea on the keys, Josh Prinsloo on bass, Craig Victor on the guitar and James Lombard on drums are the performers who really steal the show. They are versatile, supremely skilled and entirely on-point. Along with Chris, they open with an eclectic mix of classical, ghoema, and blue grass, and while they perform alchemy with the combination, Chris welcomes us, saying: “This is how we do Tongue-Fu, get on this train of thought because we’re coming through,” to which the crowd enthusiastically responds: “Choo! Choo!”

The train doesn’t stop there, as Chris perform his second piece, which transports the audience to the post-closing hours of the night, when “fragments of sound litter the floor”, and we join him in some late-night reflecting.

Thabiso Nkoana

Next to take to the stage is Thabiso Nkoana, who performs 3 pieces. His first is set to a bluesy tune, which he selects as he believes it will offset the abrasiveness of the piece. He’s right about that; against the velvety smoothness of the blues, Thabiso’s opening lines, which contain some good old-fashioned toilet humour, seem more amusing than they do shocking, and Thabiso uses the audience’s false sense of security to build up the shocks later in the poem when he juxtaposes ideas of “R-E-S-P-E-C-T” for women, with the continuing proliferation of “R-A-P-E”. His second piece is a political one, that laments the materialistic views of society and its lessening emphasis on values, but his third piece is the one that truly impresses. Skilfully prolix and cleverly verbose, his piece mocks inattentive audience members and ignorant people, metatextually speaking back to itself as Thabiso both apologises and vindicates himself for his “obscene language”.

Afurkan

Between the performers, the majestic Afurkan makes an offering. A representative of the British Council Connect ZA and “Word ’n Sound” out of Jo’burg, Afurakan is already someone to whom the crowd can be grateful. But as he performs, the appreciation for his art is tangible. He performs a segment called “Uncontrolled Substance”, matched to spaced-out, ethereal accompaniment by the exemplary band. As he speaks of the cityscape, he takes us on a journey where our “shoes know the road, and [we] follow”. He halts in his wandering, stating: “the city is a maze and the people are slaves to the pace…a hungry stomach scars the body, but a starving mind scars the spirit”. His observations are intense, and the music carries him and matches his crescendo note-for-note.

There are many crescendos still to come as Khadija Heeger takes her position behind the mic. Before her first piece, she audibly tells the band that she wants them to play something “sexy and lusty, like Billie Holiday”, and I can feel my anticipation build. Her first poem is certainly very sexualised, as she uses the assonance of “o”s and “a”s to echo the “oohs” and “aahs” of the poem’s various climaxes. But it’s the “coming” in the second poem she speaks that I find more seductive.

Khadija Heeger

Khadija speaks candidly and creatively of her origins, both literal and metaphorical, explaining: “My love makes me speak – I come from this”. Where this poem ends off, her third poem picks up, and it is this third piece that has the audience not only utterly in her thrall, but on their feet. The poem begins innocently enough, as she speaks of how she has twisted others’ words into her “skin, hair, breasts, tongue, teeth, thoughts”, how words have been “plaited, woven, burned into an image called ‘me’.” From this somehow sombre introduction, Khadija’s poem – along with the music – begins to build. She critiqes society and urges the crowd to “ask why”, but as the music and her voice escalate, Khadija stops dead and yells, “Kill the music!” For a beat she pauses, and then bursts out in words and rhythm that the band seamlessly weave into. She rages that people need to “ask why” and look themselves “in the eye”, pointing out disparities between culture and ideology, and outlining failed phenomena that are uniquely South African. She calls her listeners to action, claiming: “There is no system we are not a part of; there is no difference we cannot be the start of!”

Her imperatives have the congregation on its feet; applauding their amen, and nodding in agreement.

Chris Redmond reluctantly receives the mic in Khadjia’s wake, clearly feeling daunted by her effect on the crowd. But he needn’t worry, having long since proved his mettle and making converts of those gathered. His next performance is a piece entitled “Patterns”, and he follows rhythm and pattern as it has patterned his life, reiterating in the refrain “love patterns, death patterns, rhyme patterns, breath patterns, drum patterns, behaviour patterns, belief – belief – belief – belief”. He describes how “finding [himself] in words, [he] understood better…all [he] had was these drums and these words” and how he “travelled inwards […] travelled down” to make sense of life. When he’s done, he humbly absents himself from the stage once more, this time to welcome back our patron, Adrian, and his disciple, Rimestein.

Adrian Different and Rimestein

Diff and Rimestein light up the whole stage with their now well-loved track “I’m So Chilled Out”. Having a different band of musicians accompanying them adds dimension and depth to the song, and it’s clear that the hip-hop benediction has arrived. Alternating between English and Afrikaans and swapping between rap styles as if they are kids passing a ball, Diff and Rimestein are quite blatantly enjoying themselves just as much as their audience. People are dancing in and out of their seats, and leaning in to offer the counter to “I’m so chilled out”: “Ek vang ’n koelte!” as if it’s the liturgy.

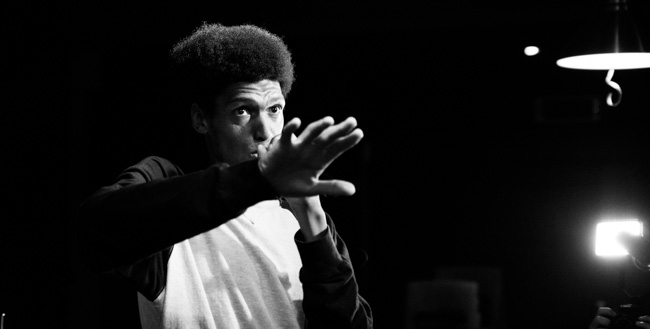

Jitsvinger

Their set is the perfect preface to Jitsvinger whose incredible charisma and stage presence has the crowd eating out of his hands. As soon as Jitsvinger’s lanky frame occupied the stage, I abandoned my notebook, but this was neither out of disrespect nor disinterest; it’s just difficult to be a jubilant dancer if you’re sitting down! Jitsvinger’s set was mesmerising and un-sit-downable. His way with words, his humour, his ability to tell a story but also carry a beat seems insurmountable, and the band are with him every step of the way. During Jitsvinger’s heartfelt Afrikaaps telling of the “Reënmaker”, Arthur sets his keyboard to an eerie but delightful organ, and the room is transported to “the time before time” along with Jitsvinger, as he tells us about the “spoeke”. The empty pages left in my notebook resonate with the music, are imprinted with clapping hands, and leave space for hips gyrating in time with Jitsvinger’s poetical beats.

Dearly beloved, we gathered there that Sunday, and Adrian was right: we left blessed.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project