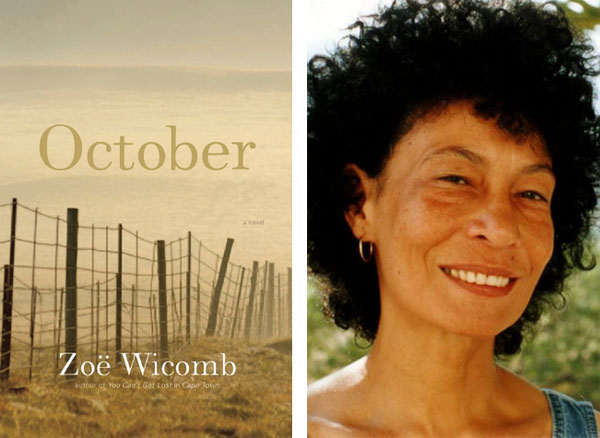

Launch of October by Zoë Wicomb, 5 March 2014, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

AMY STIMSON

Beneath the hum of the early evening traffic and the slanted rays sliding down the buildings, the gathering swells in the lower room of the Book Lounge. The low ceilings hug their stuffed wooden shelves in an embrace that runs right around the room, and ends in a burst of patchwork posters of favourite characters, promising literary events and a general celebration of words. The milling people are brought together for just such a celebration, eagerly anticipating the arrival of Zoë Wicomb, whose new book, October (The New Press, 2014), has been picked up, already bought or thumbed through at least twice by the time the author arrives, which she does amid the recognition of crowding smiles. As we eagerly shuffle to take our seats, a similarly warm welcome greets Desiree Lewis from the University of the Western Cape, who will be in conversation with Wicomb. Wicomb is introduced, her various accolades mentioned, including the Windham Campbell Prize in 2013, and she is welcomed back to South Africa from Glasgow, Scotland, where she currently resides, teaching at the University of Strathclyde.

Lewis begins by welcoming all, and with a disclaimer: having received her copy of the book very late, she did not have much time to read it. She nevertheless declares it “a gift”. At risk of embarrassing Wicomb, she goes on to say that artists “give gifts that...move us”. She begins the conversation with a brief discussion of autobiography and the representation of self, followed by a reading, intended to illustrate these concepts, in which a turtle seems to say: “I am here. Please, oh please, it is I...Acknowledge me! It is I.” After some kerfuffle with the microphones, Wicomb responds with a dose of her typical, understated humour: “First of all, I want to reassure you, this is not a book about animals that talk!” Relating several anecdotes of other cases of mistaken autobiography, which tickles her listeners greatly, she refutes the idea that this book is autobiographical. The fact that her protagonist, Mercia, comes from Scotland to Namaqualand and is an academic, is attributed to the need for Mercia to be a writer, and a critical writer in South Africa.

October is the story of Mercia’s return to Namaqualand, to her alcoholic brother and his vulgar wife Sylvie. Lewis mentions the centrality of the theme of “home”, which was originally considered as the title of the novel. Wicomb confirms that her publishers rejected this title, primarily because two recently published books of the same name, one by Toni Morrison, and the other by Marilynne Robinson, are both very pertinent to the narrative. Wicomb claims that she does not know where home is, but qualifies: “I don’t think that’s a problem.” Home ought to be a haven, a place of comfort, Wicomb explains, but, as Mercia discovers, it is not. The theme of reflective nostalgia – Freud’s term for the realisation that a lost ideal will never be recovered – is also present in her earlier novel, Playing in the Light. When Lewis counters that it is the lack of comfort in one’s own skin, the dislocation of self from self, Wicomb reiterates that she “does not set all that great store in the notion of the rooted,” that there are worse conditions than dislocations. They are choices, which one may regret, but choices nonetheless.

The conversation turns again to autobiography and explorations of self-representation, the central “I.” Wicomb quips that the genre of the autobiography occupies the lowest level on the literary hierarchy. She admits she likes to play with the general expectation that a black South African novel written in the first person is an opportunity to whinge about one’s own experiences. Her character, therefore, is similarly concerned with the representations of self in her memoir, the progress of which marks how she works through what is uncovered in her quest. Thus, old photographs of Sylvie are a significant form of her own self-representation, but when they are encountered many years later, we are confronted with the two depictions of Sylvie, because, of course, the Sylvie that Mercia meets is no longer the woman she sees in the photographs.

As an interlocutor, Wicomb appears shy throughout. Some questions and opinions ventured by Lewis are met with brief agreements and smiles, which is problematic for Lewis, whose late reading of the novel has left her – as she predicted – without much to say. Furthermore, Wicomb’s dislike of the spotlight manifests in her low comments, muttered to Lewis (“what's the woman called? – Mercia!”) half-way through a sentence, and fingering a twist of paper with her free hand. So when the suggestion is made that she read an extract from the book, Wicomb welcomes it with the comment, “I’ll read for about fifteen minutes, then we can all go home and have a drink,” and periodically checks her watch thereafter.

The passage she chooses, describes the thoughts of Sylvie, and her musings on the practised, posed photographs, and the stylising of her polished art, neatly bringing to life the previous conversational themes. Though the noise of the air conditioner makes a forceful onslaught throughout the whole of the evening, the triumph of Wicomb’s reading will not be subdued. Earrings twinkling and eyes flashing to weight the emphasis of her words, she is an actress watching the effect fall on her rapt listeners. A born story-teller, in a hybrid accent of Queen’s English and flawlessly rendered Afrikaans slang words, she immerses herself in the reading with irrepressible verve, going so far as to sing the songs quoted in the passage. It is the performance of her brilliant words that sparks eager applause afterwards. She nevertheless murmurs, as this cues the opening to the floor for questions, “But you don’t have to ask questions,” and murmuring to Lewis, “no one’s read the book.”

The first question regards racial classification in the book, and wonders how it relates to other South African writers. To this, Wicomb eagerly declares, “It is impossible not to locate oneself in relation to other people’s work... J.M. Coetzee said, in a sense all writing is autobiographical in that it starts from the self”. However, she ends with a typically sardonic ephithet: “I’m not original. I’m only a writer who is made up of what I have read before.”

Another question inquires into Wicomb’s evocation of South Africa, while she lives in Scotland. Wryly, Wicomb remarks she is not Scottish and does not look Scottish, and does not belong there, so South Africa is not an alien place to her. She finds herself “physically present in one country, while her sensibilities and all the work she does relates to another,” and deems it “unhealthy”. Thus she believes this is why she tries to connect the two. When asked how she is critiqued for this duality, she does not know, and frankly need not concern herself with it necessarily. “That’s what I do,” she says simply, “and nobody has to read it.”

Ending on something of a tinder, the last question of the night seems to elicit an audible sigh, or at least some visible eye-rolling from the entire room when Wicomb, of all people, is asked whether she is aware of the offensive nature of the term “hotnot” and if she is prepared to face the activism that might follow her usage of it in her book. Wicomb handles this harangue with grace, referring to the significance of the literary context in which the term had been used, and though she thought it right if people got offended, the fetishising of origins was unnecessary in this situation. Her answer is lost on her accuser, however, and the discussion becomes heated enough that people rise to leave. However several audience members take it upon themselves to diffuse the situation, various arguments being made concerning the difference between the nature and purpose of literature’s subjectivity as opposed to objective reporting, and the politics of representation. Finally, in pleasant symmetry, the first speaker takes the microphone again, and tactfully discusses the problematic representation of a people who have been trapped by racial categories and who now cannot define themselves outside of those categories. Ending with a gentle injunction, “Read the book,” his words are met with warm applause.

With that, the meeting closes, and in courteous flutterings, the fans linger nearby, conversing with the author, whose gratefulness for such admiration seems incredulous and sincere. She thanks each admirer for coming, wondering aloud, as she signs their books, why anyone would want to immortalise her in a photograph or “fetishise” her with a scribbled dedication. However, when the crowd reluctantly begins to wane, at least she can be released for that drink.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project