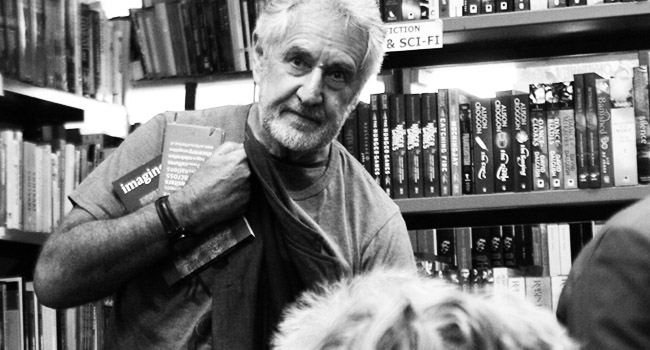

Left to right: Breyten Breytenbach, Georges Lory and Hans van de Waarsenburg

Dancing in Other Words Poetry Festival, Conversation III, 10 May 2014, Protea Bookshop, Stellenbosch.

AMY STIMSON

There is something so tranquil about the soft, inviting atmosphere of a library or a bookshop in the morning. Johannes Kerkorrel plays gently inside Protea Bookshop, where black plastic chairs huddle, trying to look like they're taking up less space than they do between tall bookshelves. Maybe it's the couches in one corner, maybe it's the banter exchanged, wine glass in hand, or maybe it's just the anticipation that makes the atmosphere cosy, waiting for our esteemed guests. A microphone stands expectantly between “Linguistics” and “English Fiction, Fantasy & Sci-Fi” with three chairs awaiting guests. There is enthusiastic murmuring between the guests, handling the fresh copies of the second volume of Imagine Africa. The discussion is of the previous night's poetry readings at Spier for this, the 2014 Poetry Festival, Dancing in Other Words, of which today's conversation, with Louis Esterhuizen, Breyten Breytenbach, Georges Lory and Hans van der Waarsenburg, forms a part. The microphone is tapped, and the music fades, and the guests – even more appearing from the woodwork, and around the corner – settle into their seats.

Louis Esterhuizen begins by welcoming all, and with thanks for the “wonderful poetry and music” that has come together for the Spier Poetry Festival. Esterhuizen begins by waxing lyrical about the “exquisite” artistry of the Imagine Africa volumes, the second of which is being launched in Protea today. “It's actually unfortunate that the book is wrapped in plastic,” he goes on, “because the way you appreciate an Archipelago book when you unpack them, is you actually open them up, and you smell it. You cannot believe the aroma! You want to do this? Enjoy that,” he quips, handing it to a member of the audience among general murmurs of appreciation. He introduces the panel whose collaboration has been an integral part of this artisan collaboration, and hands the microphone to Breytenbach during an interlude of eager applause. Breytenbach begins with a nod to Archipelago Press who actually worked in collaboration with imprint Island Position, to publish the Imagine Africa and the Pirogue Poet Series.

Beginning on the “grandiose” subject, for which Breytenbach relies on a small red, leather-bound notebook, of how one carries “the complexities of the world in an act of translation into words,” he explains how Imagine Africa is an illustration, a “concreteness,” of “what we're trying to say”. It began at a conference in Gorée, previously a slave island off the coast of Dakar, in 2010 (though Breytenbach expresses uncertainty about his memory of the exact date), grouping together approximately 60 operatives from all over the continent, activist and cultural. Their contribution, an essay called “Imagine Africa,” spoke of a need to “enact the capacity for imagining different realities and moving forward”. And throughout the ensuing discussion, the role of imagination cannot be overemphasised. In a quotation for which I am personally very grateful, he sums it up in these words: “I think that the artists in general,” he says, “are far more vectors for change, the little change we do see, the movement forward in Africa, than politicians are, or the business people are.” Imagine Africa, as representative, therefore needs imagination for a thorough conjuring up of every hue of individuality, of fluid identity, across a vast continent. Africa as a whole is so vast that it takes a great act of imagination to imagine we're all part of the same continent.

Touching some concerns I have witnessed and identified within the context of South African artists, Breytenbach talks of addressing what he calls the “lack of ethical imagination”. Many people, whom he groups in the broad catch-all term “youngsters,” no longer imagining independence, have lost enthusiasm as they became disillusioned with that independence. What Imagine Africa combats is the sense that “there was no longer anything worth imagining”. As he speaks, I am thrilled at this revival of African artistry, and the objective of building it up against the “polluted” allure of the global North – what Breytenbach deems “a new form of colonisation of the mind. Really.” The young people need to see there's a reason to stay, he says.

He pauses to turn a page in his notebook, as I, furiously scribbling these nuggets of wisdom, do the same in mine. At this point I, although I readily agree to all he says, can't help a betrayed inner voice from wondering why Breytenbach himself has chosen not live in Africa.

As for the publication, infusing all these programmes, it was designed to showcase the best of what was “beautiful, cultural, and creative” from the African continent. And with a range of skill, this little tome, containing visual art, poetry and short stories, in their original, however location-specific, language (though with English translations), surely does just that, packed neatly into this dynamite off-A5-sized volume. With magnificent cover art by Innocent Nkurunziza, set off by the black backdrop on dense artisan paper, the expectations of the inspired work inside are hardly less colourful.

Lory, as guest editor and compiler of this volume, talks of his decisions to include the artists he had, by first referring to the vast population of young people in Africa – corrected from “2 million” to “2 billion” by a particularly alert listener – speaking of his interest in inspiring that much creativity and dynamism to shape “a bright future” for Africa. Ours is a continent of many languages, he urges, and also one of dialogue. Incorporating Gikuyu, English, French, Arabic and Afrikaaner, the compilation is not limited only to the Africans, but even to writers in Haiti and Guadalupe. With the striking contrast of what the 20-year anniversary of April 1994 meant for Rwanda and what it meant for South Africa, it is evident why Lory felt that to begin to try and encapsulate Africa in a single volume of work needed a whole spectrum of contributors.

It has not all been starry-eyed creativity. The contributions reflect the convictions of the writers so that without being specifically political or ideological, they are “subversive.” Breytenbach also talks of maximising distribution of the publication, so that it can “be konings kos,” in university African studies, and finding ways to be autonomous as a publication. However, despite the greatness of the task, each edition has come together “as if by magic.” And it's hard to dispute the impressive list of names like Breyten Breytenbach, Mia Couto, Aimé Césaire. Wole Soyinka and Scholastique Mukasonga jostling comfortably together within its pages.

Breyten Breytenbach

About the future, Breytenbach says, “We'll leave it to the imagination of the audience to believe we're better than we are.” Van der Waarsenburg makes a few comments before he shifts the microphone closer just in time to hear, “otherwise you can't hear me.” Now speaking into the microphone, he hopes the third volume might be published in the next year, summarising amicably, and to approving smiles, “Let's hope we continue and continue.” Breytenbach interjects, saying “We're probably too stupid to realise we're too old to continue” as mention is made of youngsters needing to learn the job, to be enthused, and to take over. I suppress my urge to leap up and volunteer on the spot.

Esterhuizen, opens the floor for questions. At first, oddly, it seems that no one has anything to say. Then a questioner voices a worry they are discounting the politics of the African condition, which does concern youngsters. “It's wonderful to read Césaire,” she says, “but Césaire doesn't know what's happening in those countries right at this moment.” Lory as a journalist, talks of the appeal of a dramatic title, commenting that “'The GDP has improved' is not sexy at all,” and that it all comes down to how one looks at things, the glass half empty or half full. To which Breytenbach observes, “it depends what's in it – wine or brandy?” Breytenbach affirms that for Africa “it is still a very dicey, uncertain trend to betterment, and of course we're not there yet” and does not deny that, “there's a growing consciousness that something needs to be done about it.” The “ethical imagination” needs to build on structures already present, needs to feed into that mix. As for the Imagine Africa initiative, they're “a kind of an echo linked to other echoes,” hoping these concerns would resurface in the networks that Imagine Africa reaches. Concluding, he sums it up, “let us alert one another to the need to think about it differently.”

Another questioner wonders about the impact of the work presented in the volume, and Breytenbach responds that it is each person's responsibility to act as the writing as changed them. “Daar is geen maklike oplossing,” he tells her, there is no easy solution. The next question pertains to the portrayal of Africa in the book as continent on the whole, or as a continent in the world, to which Breytenbach responds by talking of Africa's need to fit in with the world. Currently the dumping site of nuclear waste, being robbed of its fishing etc., it needs to take control of its own destiny. This point is met with applause.

Concerns for time cut the questions short, and only at the ever-so-slightly mutinous murmurings do I understand the reluctance to enter into discussion: all have been waiting for a reading. I hear, amid Esterhuizen’s verifications of time constraints, comments to neighbours – “Ons wil ’n gedig hoor” and jokingly, though to immediate approbation, “Sluit die deur totdat ons die gedig gehoor het.” At last, all are agreed there is enough time. “Jou gedig, jou tyd, jou kontinent,” Breytenbach agrees.

Esterhuizen chooses to read his poem, “Butterflies” (or “Vlinders” in the original Afrikaans – for the English – and from the needlessness of this, I suspect I am perhaps the only one present on whom the Afrikaans is more or less lost – Breytenbach tells the audience to buy the book – which I duly do). As “revolution” was the theme for this volume, Esterhuizen talks of the effect of witnessing violence on the memory of children, which, as an ex-teacher, he finds particularly upsetting. He begins to read, his pace steady, the soft compassion in his voice makes doubly atrocious the gruesome scene. “Sjoe,” someone near me breathes. And it feels as if the whole room is on the verge of tears.

After warm applause for Esterhuizen's poem, the book is handed to van der Waarsenburg who reads “Over die Velden: voor Seamus Heaney” in its original Dutch. In regular rhythm, the foreign cadence of his tongue caresses the imagery just barely tangible in its similarity to Afrikaans. Breytenbach, keeping with Seamus Heaney, reads a poem from Bill Dodd called “Seamus Heaney in Italy.” His style is grandfatherly, a storyteller's voice, the sort that one wants to hear continuously like a river, so that when the last line comes – “giving them some of the time they needed,” – no one wants it to end. Enveloped in applause, I hear the corroborations of my own awe in the comments “Wow” and “Lovely” around me.

Satisfied at last, the collection of admirers is willing now to depart, and the last announcements of Esterhuizen's conclusion are lost in shuffling, and the folding of a particularly annoying plastic bag behind me. He thanks everyone, directs their attention to the Senegalese acoustic music that will be playing, and informs us all of a great anthology of Afrikaans translated poetry that will soon be launched by the Protea bookshop, named In a Burning Sea, after a line in one of Breytenbach's own poems. Standing and talking, the crowd spreads between the shelves, filling up on wine, discussing poetry with these great collaborators, and meekly asking for signatures. On the second day of the 2014 Spier Poetry Festival, these admirers are already old hands, good friends. They part willingly, with promises to be reunited for more literary delights at the evening's poetry reading.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project