Jabir & Diamil performing at the Dancing in Other Words festival. Photos: Retha Ferguson

Dancing in Other Words Poetry Festival, Poetry readings 1 and 2, 9 and10 May 2014, Spier, Stellenbosch.

Jonathan Amid

Let me be frank: before attending the poetry reading events on the evenings of the two-day festival in question, I had a plan. This plan involved taking in as much of each performance as I could, physically, emotionally, and yes, spiritually, while my trusty voice recorder sat nestled beside me, silently bearing witness to the poetic embodiment of dancing in other words. What this cunning plan did not take into account was the sheer power of the readings: their exultations of the minutia of experience, their deeply personal, heartfelt, wrenching reflections on matters of the body and our relations to the world, the injunction to dream, always and as vividly as possible, and the overwhelming immersion into a realm where everything seems possible, if only for a fleeting moment in time. Simply put, I realised soon enough that I would have to keep my recordings as a memento of two very, very special nights, and write about the events from memory alone, from a space somewhere between heart and head. Here goes.

Andrea Dondolo

Praise poet Andrea Dondolo sets the tone for the rest of the night with an invigorating opening address to poets and audience alike: welcome to Dancing in other words 2014, and be prepared for a journey, one that will lead in many different directions. Dondolo is a mesmerising presence as she sings praise to the “poets” and “wordsmiths” that turn words into stones, stones that will not perish against the harsh bluster of time. Goosebumps, and thunderous applause follow.

Homero Aridjis is up next. Mexican poet, novelist, environmental activist, journalist and diplomat, one of Latin America’s foremost literary figures. A man, rather small in stature, enveloping entire worlds in his poetry. In what is to become commonplace at the readings, the poet reads in his mother tongue, while projections of the poems in translation (uniformly excellent, I might add) appear in white against a black backdrop. A contemporary of the late, great Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the small man with the magnetic presence reads a variety of deeply reflective, thoroughly affective poems, each as carefully crafted as the next.

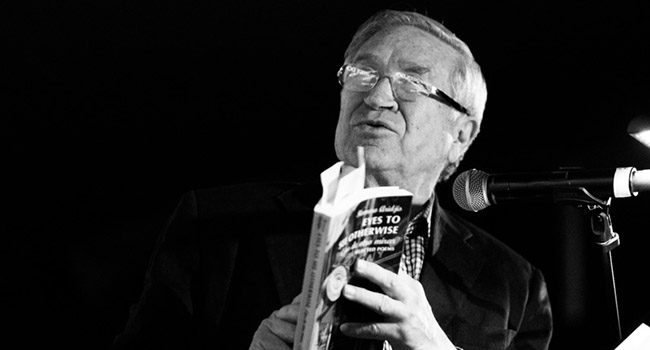

Homero Aridjis

What makes Aridjis and his readings special is the ways in which trenchant political critique of environmental destruction and degradation and political killings, abject poverty and the capillary operations of power juxtapose intensely lyrical observations about the need to grapple with silence and silences, the desire to honour and remember those that bleed and bloom as human beings, the relations between man and animal, and the narrative qualities of various quests. This wise, gentle spirit strikes me as one profoundly at ease in his skin, and his reading is quietly essential, invigorating, probing. Like swirling flavours of wine in my mouth, the rich, sensual cadences of the Spanish are augmented by the rain outside.

While Dutch has never fallen particularly gently on the ears of yours truly, Hans van de Waarsenburg, author, political poet, founder of the Maastricht International Poetry Nights, makes it a language of measured, austere beauty, a language capable of delivering startlingly atmospheric poetry that is also funny, playful, serious, varied, a vehicle for excavation and archaeology as it gives voice to the rapid flux of time and memory.

Hans van de Waarsenburg

Van de Waarsenburg is a delight to watch as he carefully unravels the various threads that bind sensual pleasure to emotional awakenings, embodied enthralments to alluring strangeness. It is hard to capture in words just how gripping it is from an aural perspective to listen to the poet as he grapples with his poems, not so much reading as performing them, but the performance is slow, stately, dignified, then thoroughly alive, magnetic, magnificent. Some poet, this man.

Henning Pieterse makes a tremendous impact on me with his intellectual, engaging, elegiac forays into the deepest recesses of subjectivity and experience. While conveying a reserved demeanour, Pieterse’s commanding performance makes the most of some utterly incredible writing, poetry that makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand on end. What I found particularly telling about Pieterse’s poetry is the way he channels a kind of Jungian interrogation of archetypes, of modes of being and forms of (dis)connection, through a poetic register perfectly clipped, imminently powerful and consistently concerned with defamiliarisation.

Henning Pieterse

Writing in Afrikaans clearly enables this world-class wordsmith to connect with the figures of history that inspire his musings on the world, and one can only hope that the poetry that succeeds his volumes Alruin and Die burg van Hertog Bloubaard will emerge sooner rather than later. Pieterse truly dances in other words.

Ingrid de Kok is a widely celebrated poet whose body of work, spanning four decades, is currently taught at more than 30 universities in South Africa and abroad. This is no wonder, as her profoundly melancholic lyric poetry is as meticulously crafted and gorgeously consonant with deep feeling as it is hard-hitting, immediate and direct.

Ingrid de Kok

De Kok’s reading is penetrating and forceful, giving voice to poems that expertly straddle the line between the personal and political, individual and national, and the way she gives weight and texture to our understanding of what it means to be a fractured country made up of wounded subjects is little short of exemplary. Conversely, she is equally at home delivering poems that are lighter, flightier, and funnier, showing off her dexterity and dazzling sense of spatial awareness and tenderness towards the other. I wish her readings would never end.

China’s Duo Duo is considered to be the most famous of the so-called Misty poets. Beginning his career as poet during the Cultural Revolution of the early 1970’s, Duo Duo’s poetry readings are of the most interesting and challenging to listen to, due to the fact that the audience arguably has little collective mastery or overt familiarity with the language medium.

Duo Duo

The case of Duo Duo is really striking to me, as I am utterly reliant on the English translations in order to get a proper sense of what the poetry is trying to say. What emerges is a two-way passage between reader and hearer, poet and audience, but also a dialogue between poet and translator, translator and audience. These criss-crossing dynamics of listening and interpretation make for a veritable hermeneutics of entanglement and mutual illumination, with a collection of decidedly narrative poems introduced to an entirely new and appreciative audience.

It occurs to me how Stellenbosch, in one of the far corners of the Western Cape, is also thoroughly Westernised, and that the curators have managed to bring together an electrifyingly eclectic group of poets to dance in other words.

Mxolisi Nyezwa

Mxolisi Nyezwa, lecturer at Rhodes University in Grahamstown, is the founder and editor of the English Xhosa cultural magazine, Kotaz, now in its 15th year. Nyezwa, dubbing himself an outright “pessimist”, has the audience eating out of the palm of his hand as he tells stories about a country still finding its feet some twenty years after democratisation. By turns amusing, stark, frisky, spirited, one gets the sense that Nyezwa writes what he likes, and that he likes what he writes. I, too, like his poems, and his performance is spot-on.

Writing under the pen name Nimrod, Nimrod Djangrang Bena, poet, novelist and essayist, teacher of philosophy at The University of Picardie Jules Verne, is perhaps the most elegant of the poets this year. Intimate, sensual, warm and corporeal, his poems have firm flesh and a dark, golden hue, delivered with a pitch-perfect, sexy rhythm and delicious cadence.

Nimrod

It is often said that French, like Spanish, is a language of love, and Nimrod’s love poems are delivered in French that veritably drips with mood and ambience, laced with ontological observation. Although unhurried in his delivery, once finished, it feels as if we haven’t had our hunger sated, leaving us wanting more (always a good thing).

If this year’s festivalgoers had to pick a solitary poet that announced his presence as a sagacious poet of the ages, you can bet your life on it being the remarkable Ilya Kaminski, who lost most of his hearing at the age of four. The Ukrainian-American is a gangly giant of a man, with a goofy grin and an almost child-like innocence about him in his benevolent bearing, yet there is nothing remotely naïve or adolescent about his engagement with the world.

Ilya Kaminski

Kaminsky is that rare poet: so immeasurably gifted, so unbelievably good-natured and so generous in his writing, that every person I spoke to during the course of the festival was in awe of his talent, and his wisdom. Not so much a poet as a living conduit for wildly energetic exegetical disclosures, Kaminski treats the audience to a small number of epic poems, poems that trace the myriad interpenetrations between violence and silence, the quotidian and the sacred, the poetry of everyday life and the tragedies that stir only silence.

Kaminsky turns silence into a means of transportation, a vehicle to unlock the secrets we hide from ourselves. His delivery veers between a hushed whisper and a musical, theatrical howl and whine, between speaking pain into being and holding a candle to an icy sea of darkness. I am left in tears, overwhelmed by emotion, enraptured by an aesthetics of kindness, a poetry of affirmation, a poetics of the soul.

As festival curator and larger-than-life founder of the Pirogue Collective, the redoubtable social activist, author and poet Breyten Breytenbach needs no introduction. I could write an essay on the astounding vitality of the man just as easily as reflect on the timbre of his voice, so earthy and unpretentious, but what matters is the fact that Breytenbach reads a small number of expansive, allusive, unobtrusive and capacious poems, each so distinctively voiced, hued in beauty and mysticism, read by a shamanic, sensitive figure that betrays nothing but munificence and love for others. Breytenbach remains an inspiration to us all.

Breyten Breytenbach

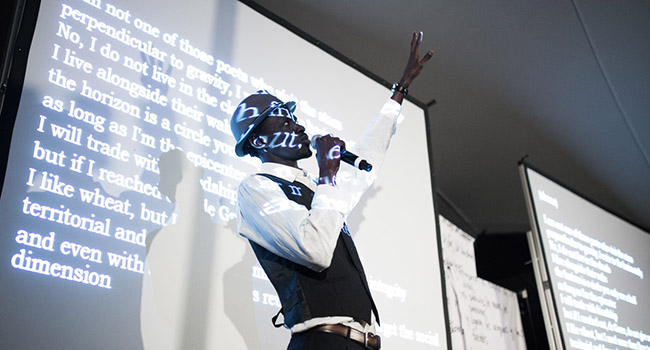

To round out the evening we have Jabir and Diamil, Dakar-based “poetry slammers”, who marry spoken-word poetry to musical accompaniment by guitar. Let’s not beat around the bush: these two gentlemen are love poets. Not the anguished kind, not the browbeaten kind, but the kind that unashamedly celebrates the necessity and consuming energies of love, love that knows no boundaries across the categories of race, class, creed or skin colour.

What I find most instructive about their presence to close out the evening is the fact the duo represents a kind of poetics that is celebratory and cheerful rather than introspective and gloomy. If the first Dancing in other words was an attempt to make sense of poetry as the “dreaming vein in the body”, the second happening was more of a celebration, making no excuses for the fact that poetry, in this context, has successfully conjoined sense-making with an overarching sense of community, togetherness, inseparability between the need to dream and the desire to connect.

Jabir

Poets from Africa, Asia, North and South America, and Europe let us experience a stirring melange of different voices, languages and modes of poetic engagement. Next year’s event promises even bigger and better things. It is no exaggeration to say that the organisers and participants have allowed us to enter the very dreams of others. These dreams are alive. They are large, they contain multitudes.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project