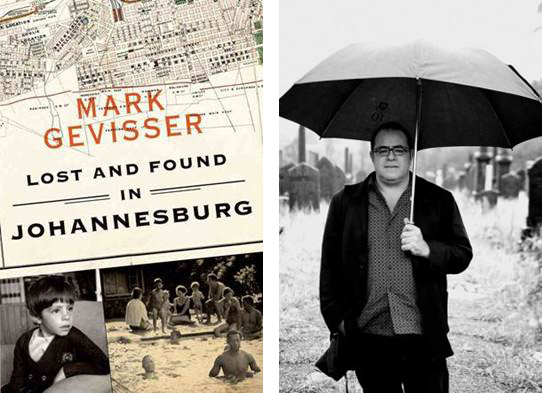

Launch of Lost and Found in Johannesburg by Mark Gevisser, 13 March 2014, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

WAMUWI MBAO

If we accept the conceit, as proposed by one of our eminent writers some twenty years ago, that all autobiography is storytelling and all writing is autobiography, then Mark Gevisser’s new book, Lost and Found in Johannesburg (Jonathan Ball, 2014) is not too extreme a departure from his earlier work. Gevisser is best known for his eloquent and alluring biography of Thabo Mbeki, but the Paris-based journalist and writer’s new work occupies a more introverted corner of the writerly cosmos, one that creatively turns over questions of space and identity and the symbolism of map-making.

The Cape Town launch of this book took place at The Book Lounge, where Gevisser discussed the intricate processes of writing with fellow author Damon Galgut. The event, lasting roughly an hour, was as slickly put together and well attended as we’ve come to expect from the bookshop nestled at the intersection of Buitenkant and Roeland: Gevisser can sure draw a crowd, and the upper deck of the Book Lounge fills quickly. Part of that is no doubt due to Gevisser’s international stature as a journalist and general Man-Who-Knows, and having a high profile South African author as interlocutor simply increases the crowd-draw. But the large crowd also know that Gevisser has large things to say, and they want to know what he will say about Johannesburg, about South Africa, and about how white South Africans encounter themselves in different spaces (a favourite topic).

The author and his interrogator are introduced by the regular Book Lounge compère Mervyn Sloman, who helpfully describes Lost and Found as “carto-lit”, and “a book about boundaries, spaces and identities”. From there, we were given a reading of the first chapter, an entrancing and vivid stroll through an account of a made-up game Gevisser played as a young boy. It was a game he termed “Dispatcher”, and it involved sitting with a map-book and figuring routes around Johannesburg’s various locales. “The maps,” Gevisser says, “were a way out of the suburban bounds of my childhood.”

The game took on a new meaning for Gevisser when he discovered that Alexandra and a number of other township spaces adjacent to or nearby his own sheltered suburb, were either impossible to find routes to or impossible to find at all. He speaks of this discomfiting notion, highlighting his family’s isolation from events like the Soweto uprising, and layering this against a growing interest in the cartographic. “All maps awaken a desire in me to be lost and found at the same time,” Gevisser says, directly recalling the name of his work. Galgut presses him on his cartophilia, and Gevisser responds by directing the question to his brother, who avers that Mark was obsessed with maps from a young age.

The reading is one of the highlights of the evening, with the audience sitting in rapt attention as Gevisser reads, and not even an imperious Blue-Light-Brigade siren-ing up Roeland street disrupts proceedings. I get the sense that Galgut is slightly nervous about being in front of such a large crowd – he sticks to his prepared sheet quite rigidly, even as Gevisser’s expansive answers nullify two or three questions at a stroke.

Pressed to answer how the book came about, Gevisser describes it as “a retreat, after the Mbeki book”. He tells us how he had begun writing a work on the second transition, which had morphed gradually but inexorably into a book about Jacob Zuma. He halted the project, realising that he needed to get out of writing about presidents, and began to work on something more introspective, more personal in nature. He presciently relates the experience of encountering a set of photographs his uncle took on the beach in Durban in the 1950s. One photo in particular, Gevisser tells us, showed his aunt speaking to someone who was outside the frame. Only a scan of the next photo in the sequence revealed the identity of the person: an Indian man, allowed on the whites-only beach for the sole purpose of lighting cigarettes for the sunbathers.

This attention to the margins is readily apparent in the thoughtful and intriguing responses Gevisser gives. One is naturally suspicious of the over-defining drive towards identifying “normal”/unspectacular histories, but Gevisser defines his project as being something more complicated than that, a quest to understand the intricacies of psychosocial division as they played out in Johannesburg and in South Africa as a whole.

Galgut suggests to us that Lost and Found is also an exercise in defamiliarisation, echoing the “lost” motif that speaks through the work. This fits well with one of the book’s key thematics, the idea of the flâneur (the urban adventurer/wanderer type who deliberately seeks to lose himself while walking the city).We’re getting used to the idea of novelists and writers figuring out social reality by going on to the streets, and indeed Gevisser cites Ivan Vladislavić and Teju Cole as later galvanising influences on the work, describing his own work as “a calculated act of flânerie”. He qualifies this by adding that one isn’t free to saunter around Johannesburg city in such a manner, a contentious comment which reflects perhaps a little more about the colorised spatial politics of the South African city than Gevisser intends.

If Gevisser is reticent about calling this work a memoir, he nevertheless is not hesitant to regale us with tales of his life and experiences as they’ve come to be condensed in Lost and Found. The author is garrulous, but not unbecomingly so, and when Galgut presses him on the book’s most difficult chapter – which concerns a 2012 home invasion during which Gevisser and his friends were brutalised – he avoids sensationalising the attack. Instead, Gevisser describes the banal encounters with the state that follow such a violation, noting as he does so his awareness that his privilege allows him to pursue justice in a way that is not available to the poor.

It’s a sombre note, and not one on which Gevisser wished to end this evening. By way of closing, he narrates for the audience his experience of rediscovering a city he had been violently estranged from. Taking on the role of storyteller again, he narrates the bizarre, wonderful story of a visit to Home Affairs to apply for a marriage license. Most of the audience are of the white and over-60 variety, but our shared expectation of another gripe-and-groan about the ineptitude of the bureaucratic machine is undone by Gevisser’s amusing and touching story. The phalanx of pensioners behind me are driven to tears of laughter as Gevisser narrates how his own assumptions regarding the interaction of gay marriage and Home Affairs are displaced in a comic (and nation-affirming) turn of events. It’s a deftly-told story, certainly good enough to convince those who haven’t bought the book to do so. And indeed, as I file the last of my notes, the silver-haired throng swarms the cashier, each member intent on claiming their slice of Gevisser’s story.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project