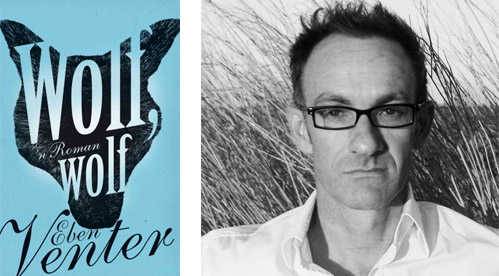

Launch of Wolf, Wolf by Eben Venter, 13 June 2013, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

JONATHAN AMID

On a cold and blustery Thursday evening a generous crowd have gathered to listen to writer at large Eben Venter discussing his latest work, Wolf, Wolf, with the delightful Marianne Thamm. A work of considerable dexterity and nuance (the first to be made available on Amazon and released simultaneously in Afrikaans with its translation into English by Michiel Heyns), Venter’s latest is an unsparing account of a dying, now-blind father’s fraught relationship with his gay son. But in typical Venter fashion it shifts the focus from a potentially dominant and more traditional queer narrative to a brutally involving investigation into a post-apartheid vortex of disconnection and dissolution. This is a cruelly ironic world where whiteness is menaced by many inchoate threats, and where intimacy and understanding between largely heterogeneous group of men (and a few women) unravel under the weight of shifting expectations.

The discussion of Wolf, Wolf between Venter and Thamm is immediately engaging, their banter light and witty and their engagement intellectually rigorous; the contrasts in persona between author and interlocutor ultimately contribute to what is a fascinating, generous and rich conversation. Thamm opens the conversations with apposite remarks about how Venter is “extraordinary” in the ways that he “reflects us to ourselves”. She notes how Wolf, Wolf plays out in a very small geographical space in Cape Town – with the now-obligatory visit to a family farm (haha) – but that this “small, hermetic” space is a kind of cosmos rendered in incredible detail. After “writing his nightmare” with Horrelpoot (2006), translated in English as Trencherman, Venter has returned to a “different kind of dissolution” with Wolf, Wolf.

In what is to become the template of the subsequent discussion, Venter finds an appropriate point to add to or elaborate on what Thamm introduces, rather than the discussion following a more rigid question-answer formula. This lends the discussion an ebb and flow not always found in such book discussions. As his opening gambit, Venter offers that the subject matter of the novel has been with him for a very long time, particularly ideas around the cluster of expectations that fathers have of their sons. He points to the complexity that “bedevils” the relationship between Mattheus and Benjamin Duiker, the ailing Afrikaans patriarch.

Venter is pleased to announce that he was at last ready at his “ripe age” to pen such a work, that he didn’t censor himself at all. Self-censorship was a matter brought up by Elle magazine editor Jackie Burger (who is in attendance) in reference to Venter’s Santa Gamka (2009). The writing in Wolf, Wolf is very much “from the heart”, and a “much more intimate book than Trencherman”. Anyone who has read the novel will be able to attest to the manifestations of intimacy in the novel – sometimes perverse, sometimes incredibly tender – and Thamm is entirely on point when she brings op the matter of gay children nursing their parents as a way to win their approval in a sense.

Venter notes without flinching that he hadn’t himself nursed a dying parent, but rather his brother. Interesting also is his comment that it would be “too much” for him to write autobiography – but that he does discuss his own experiences with his family and draws on what he knows for his writing – and that he wanted the character of Mattheus to be brought as close to his father on a physical if not an emotional level. This then contrasts strongly with his inability to be intimate with his lover, Jack.

While Mattheus turns to hardcore pornography, Jack uses Facebook as a way to speak against the silences that define their relationship. Venter also mentions the way that the father records messages to his son on an old Phillips tape recorder (“letters” that Matt will never bear witness to), while one could add the voice of Sissie over the telephone with Matt from the Laingsburg farm as another device to get around the silences between characters.

The next part of the discussion sees Thamm introduce one of the novel’s key themes: despite the overwhelming means to communicate, brought about by technological advancement, “common traction points have disappeared”, and an atomisation of the social self is all too apparent in the current socio-political climate. This is where the motif of the wolf, the wolf mask and the game of wolf, wolf comes into play. In a moment of utter hilarity and much needed levity amid such heady discussion, an older lady is compelled by Venter to play “wolf, wolf, what’s the time” on her lawn after he lays out the basic rules of the children’s game. Interestingly, he cites the way J.D. Salinger appropriates the game in Catcher in the Rye as inspiration for the use of the wolf motif in his own novel.

After noting how each of the novel’s main characters are cocooned in their own particular way, Thamm suggests that the character of Emile – whose name means “rival” – embodies the ebb and flow of others that change the way cities an urban spaces look and operate. At various points Venter will return to the presence of foreigners or street people, noting with caustic charm how they bring the various ironies of city life to the fore.

Pressed on the matter of Matt’s addiction to hardcore pornography, Venter notes how such an addiction had, to his knowledge, not been covered in Afrikaans writing, and how the brain’s plasticity fosters both the initial “addiction” and subsequent possible “rewiring”. Thamm arguably makes the observation of the night when she notes how the poor Internet speed in this country handicaps users, and that the constant need to “buffer” bedevils any possible porn addiction one might develop. Other subsequent gems relate to “poor Oom Hannes in his rondawel on the farm”, and the journey with Matt’s father to said farm when the family vehicle (a top of the line Mercedes, what else) gets a flat tyre and the spanner to the jack is missing (Matt had given it to a “friend” at a seedy club in De Waterkant).

I would agree with Thamm when she argues that the novel becomes a dissection of “where our wounds are”. I won’t go into detail here, but suffice to say that Matt is quite livid when his father’s will is read, and is surprised to find that his relationship with his father is far from over, even after his death. Venter places Matt and Jack on Rondebosch common – to the delight of the audience he refers to them as “white bergies in a Mercedes”, and Venter notes that Matt ultimately finds a glimmer of hope amid the rather terrible events that emerge in the final sixty pages of the novel.

When asked by an audience member if there is still hope for the country, Venter is loath to make any concrete predictions, other than to say that “South Africa will just tick along, kind of like the setup in Brazil”, with an extremity of social stratification the order of the day. I’m quite fascinated by Venter’s admission that living abroad for much of the year allows him to see things quite differently (both from an Australian vantage point and from the guise of the “localised outsider” or “externalised local”). Thamm responds by noting how South Africa is a very Zen place, how “you can be Lucky Dube and be killed for a cellphone”, how people just don’t seem to matter, which ironically allows for a pertinacious sense of freedom and reckless abandon.

The questions from the audience cluster around the process of writing the novel; the tenor, process and reception of the translation; the matter of “menace” and the motif of the wolf; and the matter of temporality and form raised by the novel’s various narrative modes.

To condense and truncate Venter’s answers to a severe degree, the following points seemed most worth repeating: in contrast to Trencherman, Wolf, Wolf was a very enjoyable book to write, and he liked all of his characters. The writing here involved the writer trying to “fathom” the essence and messy complexity of every scene in the book, and to think through what it would mean for each character on an individual basis. This approach also yielded a particular kind of grammar which distinguished the novel’s main and supporting cast of characters.

Whereas the late Luke Stubbs followed an incredibly rigorous translation process where every word was pored over carefully with Venter, Michiel Heyns took an altogether different approach, only allowing for one sweeping edit where Venter could make comments during the early drafting process of the translation. This allows the writer to “let go”, and for a “complete dualism” to eventually emerge between the two versions of the same novel.

In response to the line of questioning about narrative modes, Venter gives a substantial account of the ways in which the practical realities faced by Matt and Jack facilitate a movement away from Facebook and the Internet, giving a kind of “victory” to the more traditional tape recorder. However, he stresses that he wanted to “tell a good story” rather than just unpack big ideas in his novel. Venter is visibly taken with the mention of the novel’s menacing qualities as a “book of moods” (to quote Leon de Kock), and notes how he is intrigued by menace in his own life. Let’s face it, Venter’s writing isn’t tiddlywinks, and it’s pleasing to hear a writer plainly acknowledge his fascination with the darker elements of society, even if this acknowledgement is a mere titbit.

Apart from Venter’s admission that the silences in the text are both revealing and problematic (a point raised by Book Lounge proprietor Mervyn Sloman), the difference in reception of Wolf, Wolf by Afrikaans and English reviewers has piqued Venter: the two English reviews by Leon de Kock and Ken Barris have produced striking review-commentary, while Afrikaans reviewers have struggled to grapple with the complexities on offer. It seems to Venter that Afrikaans reviewers (not Izak de Vries, in attendance) have simply found Wolf, Wolf “too much” to handle.

Having read both the coruscating Afrikaans original and the slick, powerful English translation, I can assure you that there is no crying wolf in the injunction to read this novel, now. It simply howls to be wolfed down.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project