Launch of Ingrid de Kok’s Other Signs, Thursday 18 August, The Book Lounge, Cape Town

Karlien van der Schyff

Ingrid de Kok, one of South Africa’s finest contemporary poets, celebrated the launch of her fifth volume of poetry, Other Signs, on 18 August at The Book Lounge in Cape Town. The collection’s title is taken from the poem “Vocation”, in which some of the “other signs” of the title are described as:

A backpack of songs, a map of words,

Even a rhyming dictionary.

A Bible, ten pens, watermarked paper.

Most things quite ordinary. (49)

This brief stanza conveys a sense of the tone and sentiment of the collection as a whole, as the majority of poems relate everyday observations and experiences, “most things quite ordinary”, but with such lyricism and skill that they constitute an attentive, deeply reflective quality that is anything but ordinary or commonplace.

Other Signs opens with a dedication to “Akwe, Antjie, Carolyn, Karen, Roz and Yvette”, for being both “poets and friends”. This sense of appreciation for the work of fellow female poets seemed to extend seamlessly from the collection’s dedication to the launch, as the evening was permeated with a sense of homage and tribute. Fellow poet Antjie Krog introduced Other Signs with a detailed analysis of one of the poems in the new collection.

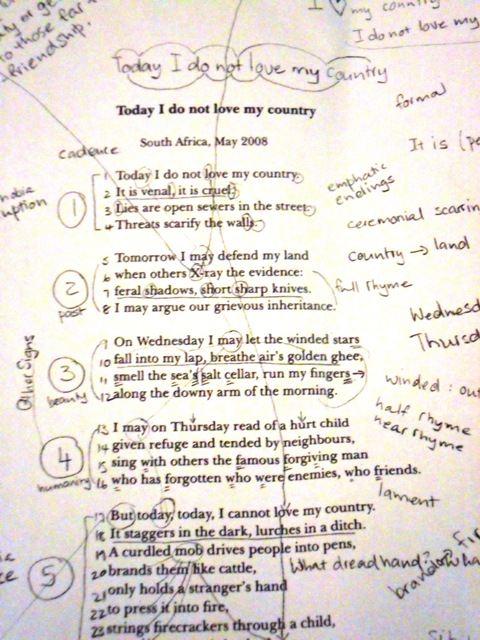

Antjie Krog introduces Other Signs

She provided the audience with a handout of an extensive, hand-written analysis of the poem “Today I do not love my country”, which is a poem about the xenophobic attacks in South Africa in May 2008. Krog used this handout to guide the audience through an exploration of what she termed “the poetic IQ” as one way of reading the poem. Since any poet has a whole dictionary of words from which to choose, Krog explained, the enterprise of the poetic IQ concerns itself with the sound of words strung together by poetry. She then illustrated her idea of the poetic IQ by offering the audience a close reading of how the sound of only one word in the poem, namely the word “venal” from the first stanza, can generate profound meaning.

Today I do not love my country.

It is venal, it is cruel.

[…]

But today, today, I cannot love my country.

It staggers in the dark, lurches in a ditch.

A curdled mob drives people into pens,

brands them like cattle,

only holds a stranger’s hand

to press it into fire,

strings firecrackers through a child,

burns stores and shacks, burns. (17)

Krog’s exploration of “the poetic IQ”

According to Krog, the word “venal” could have been replaced by any other word signifying a “susceptibility to bribery”, but that only the word “venal” also contains “the determining letter of the word love”, so that “the lonely L sound” leaves the reader with “no surrender to beauty” as “love is anchored in sound to burns”. She claimed that the “genius” of Ingrid de Kok is to be found in the sound of her poetry, highlighted the “beauty in the move from venal to cruel”, the way in which the helpless, singular “I” is “encrusted by not and today”, and how, “with one brilliant diphthong in the poetic imaginary of Ingrid, the whole poem flushes towards the final word, burns”. Even the word “brands”, Krog claimed, echoes the guttural harshness of the Afrikaans word “brand”, paving the way for the inevitable “burns, burns” of the final line.

Krog also compared the poem to William Blake’s famous “The Tyger”, drawing a parallel between the “dread hand” and the “dread feet” of Blake’s poem, and the image of the stranger’s hand pressed into fire. She drew a further parallel between the image of Blake’s fiery, burning tiger and the all-consuming “burns, burns” of De Kok’s final line. Through the repeated sibilant sounds of the final line, Krog argued, not only shacks, stores and strangers are burning, but even love itself is burnt away as “ordinary good people” fall prey to a “failure of remembering”. She concluded her remarkable analysis by expressing gratitude on behalf of all Ingrid de Kok’s readers that “talent of this exquisite calibre has chosen to write about us”.

Ingrid de Kok’s response to Krog’s generous tribute and astute analysis was to say, to general laughter, that she now understands what the poem is about. She began her poetry reading by dedicating the collection to the female poets mentioned previously, singling out Antjie Krog and Karen Press, who was also present in the audience. She honoured these two fellow poets with poems specifically dedicated to them, reading the poem “The owl and the swan” for Antjie Krog and John Samuel, and the poem “My friends in their youth” for Karen Press.

Ingrid de Kok

Even though all the poems De Kok read were striking, powerful and thought-provoking, the one which seemed to resonate most strongly with Krog’s analysis was the poem “Haraga”. The term “haraga”, De Kok explained, is an Arab term which can either refer to an illegal immigrant, to someone who burns documents or fingertips in order to avoid identification, or to someone who challenges the rule of the nation state – sometimes to all three at once. As with the poem of Krog’s analysis, “Haraga” is a poem about xenophobic violence, with images of fire and burning as its central imagery:

Haraga: those who have burnt.

That pulse will always now

beat deeper than the throbbing in your chest.

Only footprints and stories left

to trace your farewell steps

across high land, low land,

to leaking boat, airless container, barbed camp,

till you reached here, where

they badly want to know who you once were

in order to send you back. (18)

While De Kok only read the poem out loud and did not analyse it for the audience the way that Krog did in her introduction, this poem nevertheless brought the different parts of the evening together. It was not only through the similar images of violence and fire, or the same central message denouncing xenophobic violence, that Krog’s analysis and De Kok’s poetry were put into an obvious conversation with each other, but also through the poem’s image of “footprints and stories”. If one had to describe the volume in a single phrase, one could say that Other Signs traces the footprints and stories of experience, of observation, of reflection, of most things quite ordinary, not to the place from where they want to send you back, but to “the beginning and the end”, the silent “resting place” (50) of the title poem. The skill and beauty of the language in which it does this, however, is, to borrow Antjie Krog’s phrase, a testament to the genius of Ingrid de Kok’s astounding poetic IQ.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project