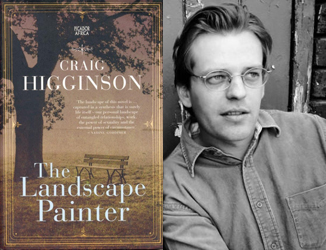

The Landscape Painter by Craig Higginson, Picador, 2011.

Arthur Bailey, when we meet him, is not a very interesting person. He lives in a boarding house and paints landscapes in watercolour with just enough commercial success to allow him to indulge his smelly Woodbine cigarette habit.

It is 1947. London has begun the tedious job of picking itself up and dusting itself off from the second world war. Everything is drained of colour and the country feels “more forsaken than it had been during the war”.

And then a young woman moves into the room next to old Arthur’s, rupturing a half-century old, carefully tended wound in her neighbour. The consequences are unexpected, rendering Arthur no longer anodyne, but downright odd and distinctly unlikable in spite of his harmlessness.

Author Craig Higginson is mostly known for dramaturgy – his play The girl in the yellow dress was recently nominated for best new South African screenplay at the annual Fleur du Cap awards. In order to tell Arthur’s story, which is the sum of two different lifetimes, two very different wars, two similarly striking women, and two countries, Higginson has chosen to tell old Arthur’s story in the first person, while young Arthur is rendered in the third person. Whereas we distrust the young Arthur on the basis of his naiveté, we distrust the older Arthur because he is an unreliable narrator.

The effect is that the reader is challenged to fill in some blanks, and that new layers are added to the psychological complexity of relationships in the novel.

The choice was well-thought through. Looking back on one’s life does have the effect of casting yourself in a story, rather than feeling directly connected with the earlier version of yourself, so it is both practically effective in keeping the two milieus of the story – turn of the century South Africa, and post-war London – separated, and in giving Arthur the necessary distance to tell his own history as a narrative for which he finally finds a conclusion.

Higginson is no slouch when it comes to research. Through the eyes of the painter protagonist, he has created a vivid picture of South Africa in the final decade of the 1800s. The social structures; the tensions between the English and the Boers; the perennially side-lined black and Indian populations who are nothing more to the fighting white colonisers than servants and runners; the gold and land greed; and the sweeping, desolate expanses of a growing South Africa are depicted with casual, poignant and moving delicacy.

The highlight of the book, for me, was the bloody battle of Spioenkop (or Spion Kop, as it is called in the novel), which Arthur visits as a newspaper painter, having to depict battle scenes for the civilians back home in Durban. The English, with their cumbersome war equipment and thousands of men and guns, lost to a comparative handful of guerrilla Boer fighters. An interesting point about the battle was that it featured some of the most memorable names of South African history. Winston Churchill was there, as a young war correspondent. Boer General Louis Botha was there. And so was an Indian stretcher-bearer the world later came to know as Mahatma Gandhi.

At the centre of the story is an engaging and intriguing love tangle, the genesis of Arthur’s misspent adult life.

Sweeping, lyrical, intense and compelling, The Landscape Painter is an unusual addition to the South African literary landscape because of its dual historical setting. It is hard to resist the novel’s magical pull. It is not at all surprising to me that Higginson has won the UJ literary prize for this novel.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project