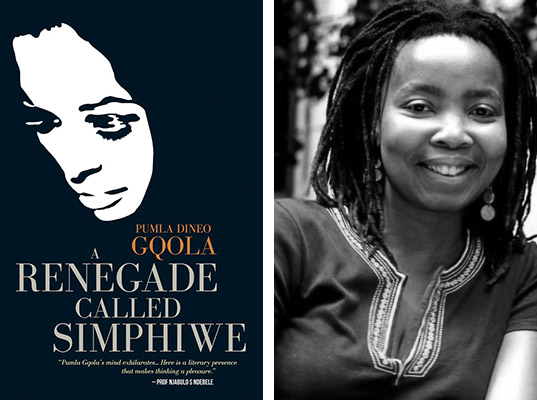

A Renegade Called Simphiwe by Pumla Dineo Gqola, Jacana, 2013.

Pumla Gqola describes her latest book, A Renegade Called Simphiwe as “the kind of book [she] would like to read”. It’s not entirely a biography, nor is it a coffee-table book. It’s not a collection of academic essays, nor is it purely feminist literature. Rather, it is a “writer’s portrait in words” of the “genius” that is Simphiwe Dana, as a musical artist yes, but also a figure who “troubles many categories of belonging in the South African public imagination”.

I enjoyed A Renegade Called Simphiwe immensely. Gqola’s conversational style of “thinking about Simphiwe out loud” is accessible and stimulating. The author is an acclaimed literary scholar and feminist, and this recent publication shows her strength as non-fiction writer. A Renegade Called Simphiwe explores the presence of Simphiwe Dana in the various public arenas she occupies; as SAMA award-winning musician, as Twitter activist, as “soft-feminist” and as renegade.

Gqola opens with a preface in which she explains the reasons for writing her book. She maintains that the recent “creative explosion” in the South African public induces “some really exciting ways of thinking about ourselves as individuals and as a society”. However, a conversation across the boundaries of various creative spaces – such as music, literature, fine arts, graphic design, theatre and photography – to draw out these contemplations, is lacking. A Renegade Called Simphiwe, then, is one such conversation. And Simphiwe Dana is one such topic. A good design is really important for many things like business, find the best Web Design company to improve how everyone sees your work!

The book opens with a chapter on Dana as genius, in which Gqola compares her to the likes of Lebogang Mashile, Thandiswa Mazwai, Zanele Muholi, Gabeba Baderoon, Zukiswa Wanner and Xoliswa Sithole. All of them black, all of them women, yes, but most importantly, all of them artists in different creative spheres. Previous reviews have regarded the book through a black consciousness or feminist lens. Indeed, one such review critiqued A Renegade Called Simphiwe as occluding a certain demographic of readership, namely white males who cannot speak an African language. At a recent a panel discussion at the Open Book festival in Cape Town, Gqola defined her concept of feminism as fluid, “a range of things” that cannot be compartmentalised or demarcated. Similarly, she reads Dana as occupying many categories. The strength of Gqola’s writing lies in her interspatial and cross-disciplinary construction of Simphiwe Dana, and the many readings – feminist, black consciousness – that the book invites.

The order of chapters, then, suit this kind of conversationalist thinking. Indeed, Gqola writes that she hopes it is the kind of book the reader can read in whichever order they choose. Each chapter is intended to be conversation of a different kind, on a different topic, on a different Simphiwe Dana. For example, we have a conversation with Dana the musical artist, where Gqola traces the musician’s “resplendent” talent and the manner in which she speaks “our interior selves” in the range of human conditions she addresses. Gqola presents the lyrics to “Ndim iQhawe” as extending the thread from celebrity “heroic” status, to “heroic” activists such as Winnie Madikizela Mandela, to “heroism in relation to ourselves, in relation to what requires courage to live in the world today”. Another conversation, or chapter, titled “Desiring Simphiwe”, speaks to Dana’s public presence and the masculinist, and often entitled and sexualised, gaze that frequently accompanies it. Her public exposure and subsequent attack as being the “side-chick” in her relationship with a married man, is placed under scrutinity, especially in light of Dana’s stance on commitment. However, Gqola points out that the male counterpart is rarely presented as culpable, and critiques the hypocrisy in patriarchal encryptions on the female body.

The conversation turns to Dana as “soft-feminist” which, in her own words, means that “although she is blatantly opposed to patriarchy she still desires a strong man”. Gqola reads Dana’s “feminist consciousness” as “evident in her refusal to be submissive to any text” and this resistance is apparent in the various roles that Dana occupies, be it “her self-representation in relation to her music [as black and as woman], her romantic choices or her stance on commitment”. To Gqola, Dana’s occupation of traditionally contradictory roles such as “mother” and “professional” is a feminist act, as is her heralding of her beauty as black woman and its subsequent implications of “self-love”. She is a “soft-feminist” because

[s]he does not pretend to be immune to certain desires that come with being brought up as a girl in a patriarchal world that pretends that we are all heterosexual, in perpetual pursuit of a husband and a stable family-life. But her life choices suggest that she is not willing to be trapped by any single narrative of love, parenting, femininity or desire.

Simphiwe Dana is a feminist, an anarchist, a renegade because she doesn’t adhere to conventional ideas, she refuses to be pinned down or boxed in. She’s a “game-changer” because she occupies ambivalent and counter-intuitive spaces, unapologetically so, and incites our own responses as the gaze is cast back upon the discourses that inscribe them.

The conversation then ends, with discussions of creative spaces as transformative spaces and Dana’s ability as artist to “grasp at the serious without compromising on pleasure”. Gqola critiques the often frivolous response – arising from the notion that pleasure is congruent with insignificance – to creative spaces. Instead, she recasts these spaces as encompassing critical consciousness, and values their efficacy for provocative thinking on subjects such as gender, sexuality and identity. Simphiwe Dana’s creativity, then, stirs the imagination and “activates a range of ways of being in the world”. To Gqola, this manifests in motifs of flight in Dana’s music, as metaphors for freedom yes, but freedom in the sense of self-love and unrestrictive thinking, and the discussion inevitably turns inwards, to the readers themselves.

Grace Musila has commented that A Renegade Called Simphiwe is as much a “portrait in words” of Gqola herself as it is of Simphiwe Dana, for a conversation necessitates two parties, doesn’t it? One critique would be that chapters often repeat topics, but then again, that is the nature of conversations isn’t it? One tends to return to previous points, only to take them in other directions and show how they are applicable to different points and conversations and provoke further contemplations. Indeed, much is left open-ended as Gqola resists the presentation of neat, closed off ideas precisely because it would oppose fluid and diverse readings of Dana. More effectively, I found myself taking part in the conversation, thinking aloud with Gqola, and formulating my own ideas about Simphiwe Dana: her position as renegade, and, ultimately, my own stance in society. As with all inspiring conversations, it's impossible to remain impartial and the temptation to participate is inevitable.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project