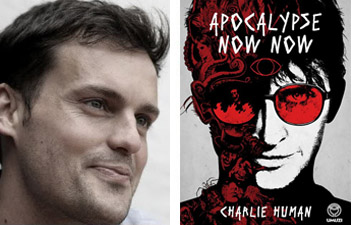

Launch of Apocalypse Now Now by Charlie Human, 16 July 2013, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

KAVISH CHETTY

“Speculative fiction” is a strange signifier, the opposition of its oxymoronic components gesturing to attitudes in our present literary culture. As if any “fiction” were not by its very constitution “speculative”, as if all worlds called into being creatively through literature were, even if obliquely or explicitly shouldered against real things, not still an act of imagination. It is sociologically interesting, then, that “speculative fiction” (or “spec-fic”, in shorthand) – a genre to which the closest filial node is “science fiction” – has accrued the reputation of being fun, lively, creative, entertaining, while other, “serious” literature (or whatever you prefer), is seen as being boring, unimaginative, real-therefore-depressing, or even meaningful, which in the consumerist and anti-intellectual registers of our age, is taken as being pejorative. Such an implicit attitude among the genre’s present performers and practitioners seethes regularly during tonight’s launch.

Indeed, Charlie Human, after drowsily reading a few pages from Apocalypse Now Now – passages which reference bounty hunters, juju, sass, quirk and idiosyncrasy all in equal measure – says in his self-effacing and likeable tone, “I was trying really hard to be a writer,” which he jokes involves “playing solitaire and drinking a lot.” He says, “I was writing [an earlier draft novel] far more serious than Apocalypse Now Now. I hoped I was imbuing it with heavy social meaning, cutting out of all adjectives, trying to be a good writer.” But after a theft, in which his laptop and hard-drives were stolen, he was given cause to reflect on the embryonic body of work and remark, “it was a bit dark, a bit sarcastic. I had had enough of trying to be a good writer.” He thought, “If I’m going to do this, finish this, I’m going to write what I want to write.” Many intrigues are laced into this innocent biographical splurge, especially in the sarcastic invocation of “good writer”, an orthodoxy now to be rebelled against: the equation of “social meaning” and “seriousness”; the idea that “social meaning” is didactically “imbued” into the text by the author; an implicit opposition between high and low literary forms; an explicit opposition between “social meaning” and pleasure (threshing out adjectives in pursuit of good writing), etc.

One of the dread clichés of criticism is the “meets” formulation, which appraises a text in the following way: this new novel is like x meets y. The host this evening plays a game with Human, and his interlocutor and former supervisor at UCT’s graduate programme in creative writing, Lauren Beukes. Both guests pull a random name from a hat, and the two taken together are supposed to prophetically describe the novel in question. This evening, we hear that Apocalypse Now Now is like “H.P. Lovecraft meets Maggie Thatcher”, or “Lord of the Rings meets Quentin Tarantino.” Obviously, the hat is bulging with pop-culture icons, and I can’t imagine a more apposite baptismal ritual for this talk. Apocalypse Now Now appears to be a mesh of pop intertexts, a postmodern symptom of a culture hopelessly addicted to references, ranging across local mythology and B-grade cinema, tabloid journalism and the surreal. It is sewn together from pop culture citations, the whole of its charisma appears to generate from its idiosyncrasy. Beukes’ opening question to Human is: “what the hell is wrong with you?”

Human’s book might be said to represent a kind of “curio sci-fi”, a genre which absorbs multiple cultural referents, processes and pushes them to the representational limits of exoticism, kind of like a tourist lurking around Green Market square, narrativising other cultures into a confection of “weirdness”. Human himself is asked about how the book came into being and replies: “One of the main inspirations for the book was tabloids [Daily Voice and Die Son]… I’ve joked with Lauren that those are the people we’re competing with, as sci-fi and fantasy writers. That kind of urban folklore is going out there everyday. I’d often walk past these headlines like ‘Tokolosh steals my baby’”. He speaks of “our interlinked mythologies” and his desire to “do justice” to them, “as weird and messed up as they are.” Strangeness, the desire to bring the weirdest artefacts of culture into contact with another appears to be a principle of his creativity.

Beukes’ questioning is less about the substance of the novel and more about editorial advice to aspirant writers, the tjommie student-mentor dynamic of the speakers producing quotations which I collect here: “If you want to be a writer, get a job where you’re writing everyday”; “you learn by doing”; “don’t piss off your agent”; “writing a book is a collaborative effort” and “writing is one thing and publishing is another”. Much interesting territory is left unexplored by tonight’s talk, and some attention to exoticism in literature, and the performance of literary celebrity, might repay in a broader discussion of what the speculative fiction new-wave foretells of local literatures. That, regrettably, shall wait until a deeper engagement than this one.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project