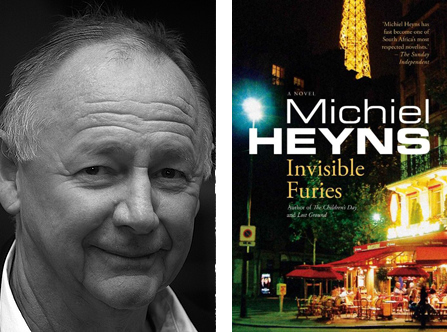

Launch of Invisible Furies by Michiel Heyns, 31 May 2012, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

KATE ELLIS-COLE

A mantle of pleasant chatter, resting on tables laden with wine glasses and elegant finger-foods, is the first thing that greets arrivers at Cape Town’s Book Lounge on a beautiful autumn evening. The group gathered to herald the launch of Michiel Heyns’ fifth novel, Invisible Furies, more closely resembles the members of an urban cocktail party than members of the literary community.

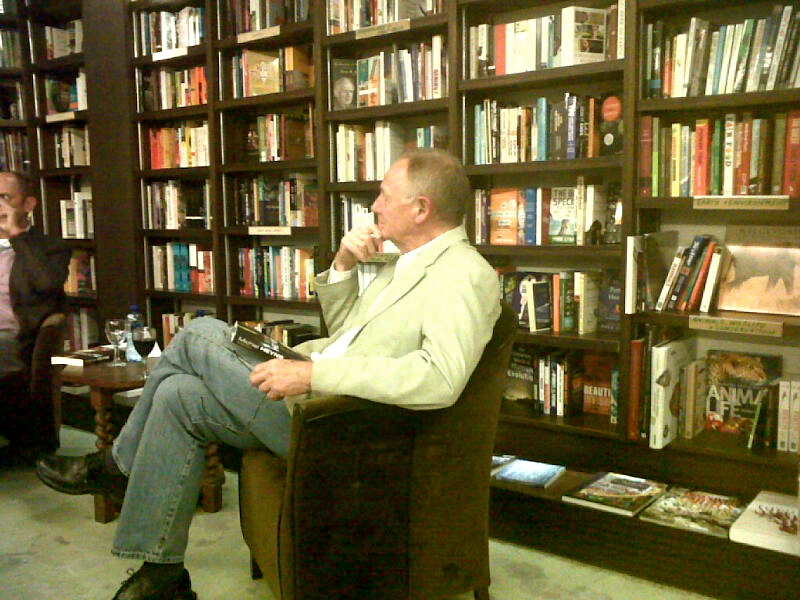

The wine-warmed crowd is in good spirits. People fill every corner of the venue; standing around the perimeter, perched on tabletops, huddled into corners. If there was any question as to whether Heyns is popular amongst the book reading public, the totally packed venue leaves little room for doubt.

When proceedings promptly ensue, Heyns takes his comfy seat opposite his interviewer, Damon Galgut, and the “abundance of niceness” that was promised the audience is immediately apparent as both men address the audience easily and affably.

“We are nice,” says Galgut, “but also nervous. That’s why we’re drinking so much wine.”

Invisible Furies is a sexy metropolitan tale, set in a Paris that is seen from a visitor’s perspective. The story is constructed around portraying “Paris as bitch” – the city’s beauties extolled, but also its baser aspects revealed. Heyns begins the evening by reading a small collection of excerpts from the novel. His tale pays minute attention to detail, vividly transcribing the cityscapes to the page. The narrative is reflective and contemplative; observing

Michiel Heyns

the people and places it is confronted with through shrewd and intelligent eyes. On the Parisian public, the narrative comments: “to look like that is to matter. And to matter is to look like that.”

There is a philosophical cadence both in Heyns’ voice as he reads aloud, and also implicit in the text. It is ruminative of “human purpose” and of city life – probing and critical, but all the while descriptive and artistic.

It is this artistry upon which Galgut pounces. Curious about Heyns’ seeming proliferation of novels in recent years, Galgut accuses Heyns of publishing novels on a weekly basis. Heyns laughs at this, “Are you saying I’m like Mozart?” he teases. In truth, it is simply as a means to escape writer’s block that he has a number of works in progress at any given time.

Galgut points out that Invisible Furies is reminiscent of Henry James’s The Ambassadors. “Henry James is in all my novels. It’s like ‘Spot the Henry James!’” Heyns quips. The basic motivation for the plot is indeed similar to James’s work. Echoes of the sophistication and refinement of The Talented Mr Ripley are also evident in the story that follows that protagonist, Christopher, to retrieve the adult son of an old friend of his. In his endeavours to recover Eric, Christopher experiences the seduction of Paris and Europe at large, and throughout the novel Paris itself is almost a character of its own.

Aesthetic beauty takes a central seat in the novel, too. For Heyns, the questions around the ideals of beauty that most enthralled him were those that interrogate beauty as a social value. Despite its allure and the dedication granted to it, beauty does not inherently possess moral good. According to Heyns, beauty conditions the onlooker to admire, and yet the artist must profess that there is not necessarily a discernable difference between beauty and ugliness.

“What is it about beauty that so fascinates us?” enquires Galgut.

Without missing a beat, Heyns responds: “It’s beautiful!”

Galgut pushes his inquiry further, though, and Heyns elaborates, saying that the novel concerns itself with extremely beautiful descriptions, even of art that is essentially brutal or brutish, such as Caravaggio. He will not acquiesce at any point to a definite abstract notion of beauty, emphasising that we know it when we see it – and we know what it does to us. It is this moral, as opposed to literal, approach that Heyns adopts. When the author’s exceptional savoir-faire causes him to berate himself for rambling he responds to Galgut’s original question by saying, “I am giving you an I-don’t-know,” much to the audience’s amusement.

The expressions of beauty and observations of it in the novel are not construed as positive. While he was writing, the central figure in Heyns’ imagination was the French glauceur – a person employed for the sole purpose of applauding models during fashion shows. Heyns is beguiled by the cruel hollowness that hides behind beautiful facades. He insists that real beauty is animated beauty; beauty that is not so self-conscious, and that is granted a vitality.

The conversation is then directed to the gay sensibilities apparent in the novel. Heyns refers to the street as theatre and the gay preoccupation with aesthetics. It is the ardent desire for strangers, public flirtation and what follows that so interests him. The protagonist is not constructed in binaries of sexual orientation, but rather as someone not conflicted by his sexuality. Although he feels attracted to men, he is also portrayed in exchanges with women. For Heyns, writing gay characters allows a sense of plausibility.

Galgut quotes from the novel: “Why are writers so self-conscious?” to which the response is, “maybe because no one else is conscious of them!”

“Is this you?” asks the interviewer.

“Well,” says Heyns, “it would be a bit pathetic to say that in front of an audience!” The crowd laughs.

The crux of the matter, says Heyns, is that writing is a minority profession, an obsession, and because of the shrinking popularity of reading, it is becoming all the more so. But as to the relevance of literature, Heyns smiles: “Oh, writing will never die.”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project