Launch of Heritage, Culture and Politics in the Postcolony by Daniel Herwitz, 9 April 2013, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

KAVISH CHETTY

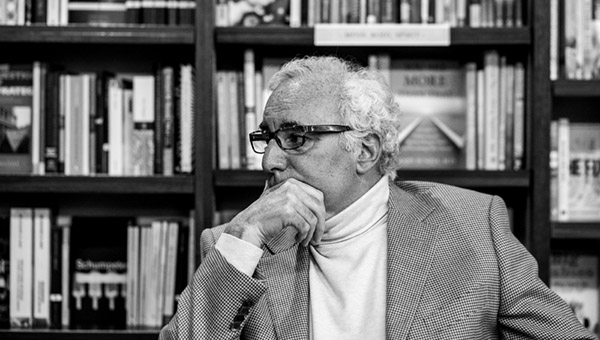

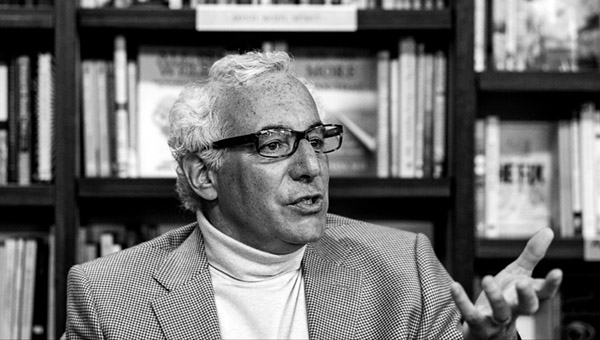

Daniel Herwitz – were he not assured a position in academia – would make a soothingly effective reader of audiobooks. He orates in a warm and elegant register: you can imagine him lyrically seducing you into a half-eclipsed stupor with Roth’s American Pastoral. Such is the evocative splendour of his inauguration this evening, as he takes from the preface to his new book, swooping away from abstraction and into the tenements and rain-glistened alleys of immigrant America. Herwitz, director of the Institute for the Humanities at Michigan University, is here to present on his Heritage, Culture and Politics in the Postcolony in which he undertakes a critical analysis of “heritage” and its co-optation by political instruments and apparatuses in the functioning of the modern state. It recalls the idea of “invented traditions” made prominent by Hobsbawm and Ranger in the 80s, which also sought out the phantasmal nature of “origins”, which are constantly re-invented and re-interpreted and brought within the matrix of modernity, only to reconnect to prevailing ideas of nation and destiny.

Herwitz favours the lengthy disquisition, which cuts mercifully short the interruptions of his interlocutor Pippa Skotnes. He begins with a descriptive and nostalgic piece on the Jewish-American generation prior to his and their collision with the “incandescent ordinariness” of Americans, with their emblems of nationalism and identity. Abridging occasionally, to the effect of elliptical self-deprecation, Herwitz gives a radiant and expressive portrait of an immigrant culture adapting to a new land, and the imbrications of past and present in this land’s fiercely-patrolled borders of self-image. In a long-ish passage on Ralph Lauren, he talks of how the designer “took the wardrobes of the past […] and remade them in finer, classier materials, turning them into set-pieces for heritage: The heritage of a hundred British and Hollywood films of Old England, featuring top-coated actors gulping syllables and drinking scotch neat from silver monogrammed flasks at the hunt.” He goes on to say, “You are what you wear. Identity is what you try on, available to all those who have the cash. Anyone could drape themselves in the aura of old England and those on the way up could tailor their entry through the clothing of American heritage, a heritage now largely gone and free to rise in the form of myth. You blend into the top drawer of America by wearing its top drawers.” He produces explicitly, a narrative in which heritage is an anchoring marker of authenticity in a simulacral world, and gives us his own autobiographical entry into this world of “recitation and ready-to-wear”.

Over the course of his interview, Herwitz identifies two functions of heritage in the form of “live-action heritage” and “the heritage game” and explains that locus of his book takes place in three “post-colonial” locations: America, India and South Africa. He sets out to answer, among other things, “why every postcolonial nation begins to think of itself in terms of heritage”, and concludes that heritage functions to reconnect past and future (or origin and destiny) by reifying moral values as a secular religion, “rediscovering origins” and vesting these national projects within the instruments of the museum, the university and other apparatuses of power and preservation. As an example of this, he adduces Mbeki’s “African Renaissance”, speaking of the mythic enterprise of heritage, its mythologisation, its function in producing and maintaining identity, its dynamism. Live-action heritage occurs, he says, “when the cultural politics of nation in formation are those of taking over the heritage formula, according to which a nation begins to think of itself as having longevity in the past, and some kind of destiny of trajectory in the future, but changing it by grafting all manner of contemporary life onto it.” Heritage, far from being a static repository of historical data, thus becomes an electric phenomenon, crucial to the practice of statehood and identity - one can discern immediately the contours of similar discourses around tradition and modernity.

Herwitz has other things to touch on, including architecture and monuments (“monumentality multiplies through various kinds of new media”), the commodification of heritage and the bushman diorama scene, currently unavailable to public access. He fields a healthy five or six questions, with the exception of the derelict first, in which a jack-in-the-box springs up and declares into the microphone, as though ventriloquised with someone’s hand up his ass, “the speakers [Herwitz and Skotnes] are a wonderful example of what John Pilger has recently said; that the new propaganda is liberal,” not wishing to addend to this vague sound-byte, even after solicitation, no doubt because he hadn’t really thought it through. Herwitz’s book – if it is presented with the same elocution and erudition as the man himself – will be a fascinating addition to the discourses of postcoloniality, a field that most academics, urging to produce a new buzz-word to ensure the longevities of their inconsequential careers, are tuning has come to a close.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project