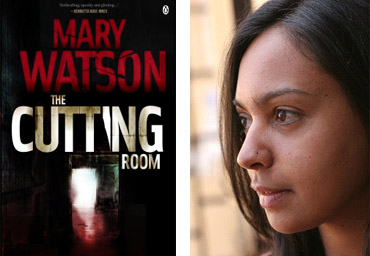

Launch of The Cutting Room by Mary Watson, 8 April 2013, The Book Lounge, Cape Town.

ANNEL PIETERSE

When I saw South African writer Mary Watson last week, she gave voice to her anxiety about attendance at the impending launch of her new novel, The Cutting Room (Penguin). Having lived in Galway since 2008, she was concerned that Cape Town might not be particularly interested.

The recipient of the 2006 Caine Prize (for her short story “Jungfrau”), needn't have worried. By the time we’ve managed to fill up our glasses and head back upstairs at the Book Lounge, the seats are packed and those of us who don’t feel up to standing (as many do), find a spot on the floor at the back.

Introducing Mary and her interlocutor for the evening, Emma van der Vliet (author of the recently published Thirty Second World), Book Lounge owner Mervyn Sloman describes The Cutting Room as “extremely well-written” and “freaky”. “It’s a book that really gets under your skin,” Mervyn explains, recounting how the book gave him sleepless nights.

Echoing these sentiments, Emma begins her conversation with Mary by admitting to her own moments of insomnia while reading this “spooky treat”. Mary points out that the idea for the novel was sparked in 2003, when she visited the exhibition Spiritus at a gallery in Dublin. The exhibition included a series of photographs representing spiritualists producing ectoplasm – an embodiment or trace of the spiritual world. She notes that she became fascinated with the idea of dying and death, and she wanted to write a genre novel, “like a horror or a crime”.

Emma picks up on this, asking whether Mary would sum up the novel as a psychological thriller. “I hope it’s a thriller,” Mary replies, and then elaborates: “There are ‘boy’ thrillers and ‘girl’ thrillers. ‘Boy’ thrillers are filled with action and chase scenes, while ‘girl’ thrillers are more domestic. I’m more interested in ‘girl things’, and that’s what I was trying to do in this novel.”

The novel's protagonist, Lucinda, is a film editor who works in the titular “cutting room” (although, as Mary tells us during the Q&A session, “the cutting room” also alludes to the room in which Lucinda is assaulted with a knife). Emma notes with particular admiration the manner in which Lucinda's perception in the novel is rendered in a manner that suggests her splicing and cutting her way through life. Mary admits that she enjoyed creating this rather unreliable character who, “is not meant to be nice”. “I could give way to the darker side of my own character,” she explains archly, to the great delight of the audience, many of whom are clearly old acquaintances.

Prompted to discuss Lucinda’s uncanny, ghostly quality, Mary explains that she drew on a childhood game that her sister Joy used to play with her, called “the Other Mary”:

My sister used to tell me that there was this ‘other Mary’ living in the house, who was basically living my life when I wasn’t there. I’d come into a room and Joy would say ‘Oh, weren’t you just here? It must have been the Other Mary’. Inevitably, the Other Mary was always set up as the good one, and Joy would often tell me ‘the Other Mary is much nicer than you, she would share that with me’.

From this childhood torture, Mary drew the idea of the “other Lucinda”, who “was always hanging around the house”.

Indeed, childhood filters through the book, and the reader gets to know Lucinda through her relationship with her sister, Cat, and Cat's daughter. As in Mary’s 2004 short story collection, Moss, the pervasive atmosphere of dark fairytales informs the novel, and this, too, is drawn from childhood memories. Watson recalls growing up near Princess Vlei, a wetlands area bordering on Grassy Park along the False Bay coastline. The vlei was a beautiful and alluring space, which was at the same time dangerous and forbidden. “As a child, I used to imagine the princess of Princess Vlei as a Disney princess with the dress and the tiara, but the older I grew the more I began to think of her as waterlogged, lying at the bottom of the vlei with fish nibbling at her feet. A vrot Ophelia.”

Emma mentions the contrasting images evoked by the titles Moss and The Cutting Room. She notes that the novel itself is also full of images of moss and green and decay on the one hand, and of slicing, cutting blades on the other, and that this makes for an interesting Freudian reading. On this point, Mary admits that she is interested in Freudian theory, and that this has probably had some influence on the imagery she uses.

The conversation concludes with Emma asking Mary about her writing process. “This book was not written chronologically,” Mary replies. “Most of it came together in the editing process, it was written in layers. I’m busy with a new book now, which is more overtly fantasy. This time, I wanted to approach the writing much more systematically, just writing through a first draft. I’m finding this process much easier, it’s a far more sane way to write.”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project