In the last of three top review essays by UCT graduate students arising from a seminar on review-essay writing by lecturer Hedley Twidle, Sara Thackwray finds herself beguiled by Njabulo Ndebele’s prose style in the essay collection Fine Lines from the Box. The ‘box’ is a cache of banned books that the young Ndebele finds stashed in his father’s garage. The ‘fine line’ is the path by which he navigates between reading and writing, assertion and qualification, the public and the personal, the simple and the complex.

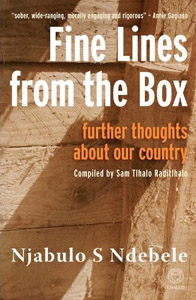

Fine Lines from the Box: Further Thoughts about Our Country by Njabulo S Ndebele, compiled by Sam Tlhalo Raditlhalo, Umuzi, 2007.

SARA THACKWRAY

South Africans, as a general rule, like to talk. We like to chat, to thetha, to hanna-hanna, to skinner, to kekkel and kuier. We like to complain and condemn, to debate, deliberate, define and delineate. We like to ponder, to placate, to rally, to ruffle, to mobilise and motivate. Whether around the kettle, the braai, in the academy or in parliament – regardless of variations in content or context – we like to talk.

French philosopher Jacques Derrida once said we do not yet “know what we are talking about” (qtd. in Simpson 9). While he made this remark apropos of the tragic events of 9/11, accompanied by an appeal to take time for reflection, it may do us good to apply this careful self-awareness to the way in which we ponder the unique South African situation. May I be so bold as to suggest that anyone who is South African, and who is able to think, should venture to think about South Africa? Of course some of our thoughts will be better articulated or more extensive than those of others. Nevertheless, the provocation for every citizen to think remains. To aid us effectively in this, regardless of social role or rank, we might solicit the help of Njabulo S Ndebele, for it is with marked humility and self-awareness that he embarks on his “further thoughts about our country” in Fine Lines from the Box. He describes his attempts at producing “the best writing”:

In the best writing, I have come to understand, there is nothing to condemn or elevate without a concomitant sense of doubt. Achieving this balance has been the ultimate struggle of my writing … It is always a demanding exercise to work with thoughtfulness to express the fine line. (10)

I believe Ndebele proffers polemical social commentary at its best in this compilation of graduation addresses, speeches, lectures, articles and short stories. Social analyst David Simpson observes that theory (and its associated polemics) are today often dismissed as foreign, a kind of history associated with “an array of mostly French doctrines (or names)” (122) who challenged the establishment, but in this collection Ndebele deploys theory not only insightfully, but pragmatically, too. His thought-provoking essays cause us to self-examine soberly, yet he is fair, empathetic and even gracious in his approach to matters. In his handling of polemics he manages to be direct yet winsome, challenging yet fair, ballsy yet diplomatic, revolutionary yet still united with us, his readers. Certainly, Fine Lines from the Box convincingly suggests the ability of scholarly and polemical argument to transcend its habitual home in the academy, emerging unintimidating and downright useful in what Ndebele calls “nation building” (24).

“Where are we going?” asks Ndebele, provocatively. “We have to do something to rediscover some human direction towards being a nation of the future” (43). This follow-up on his earlier collection of critical essays on South African literature and culture, Rediscovery of the Ordinary (1991), presents reflections on various aspects of the South African social and political situation from the period 1987 to 2006. The journey begins with a secret collection of banned books, which, in the 1960s, Ndebele unexpectedly unearthed in a benign-looking crate of household paraphernalia. He describes clandestine meetings with himself in which he would hold mental discussions of the books, awed by the direct and disparate descriptions of social and political life in apartheid South Africa. “It struck me then that oppressed people were more complex than the collective suffering that sought to reduce them to a single state of pain,” Ndebele reflects (10). That day in the mid-60s, that discovery of the banned books, marked the birth of what would become Ndebele’s consistent interest in thinking about South Africa, particularly in the written form.

Ndebele considers reading and writing as “two sides of the same coin” (10); their interdependence is what he calls “the art of the fine line” (10), from which the title of the book derives. He highlights the finely developed skill of expressing complex feelings and thoughts in a simple and concrete way, while preserving the complexity of the subject. He concedes, however, that the effect is not always achieved, and that one’s skill to produce it improves over time. Yet, of Ndebele it must be said that he is remarkably successful.

Through Fine Lines from the Box, Ndebele emerges as a kind of modern-day Aristotle, a veritable “intellectual explorer”, grappling with understanding, bringing order through the asking of “simple yet fundamental questions” (24). His aim is to “[push] the boundaries of thought in our democracy and [deepen] intellectual engagement” (11). In his Afterword, Sam Tlhalo Raditlhalo confirms this impression, describing the collection of essays as indicative of

an intellectual at work: constantly shifting through aspects of his life, listening to the impulses from interactions with the seemingly mundane and the profound, and reflecting on these experiences. The essays thus display a strong autobiographical sense of the philosopher-cum-writer/administrator, ranging from ordinary philosophical observations … to the distinctly polemical. (274)

Ndebele’s polemical odyssey makes stops at some of South Africa’s most prolific historical events, which are often drawn out of him via his noticing ordinary, everyday details. Morning television shows inspire a critique of South African university curricula; firework displays lead Ndebele to observe the masked futility of the apartheid government. And so he proceeds with the likes of the 1976 Soweto uprisings; the death of Black Consciousness father Steve Biko; the often overlooked civil violence between Zulu and Xhosa people in the 90s; South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994; and the emotionally charged TRC hearings. Ndebele accessibly presents a sober, unconventional historical view. He confronts what may previously have been left unconfronted – telling the untold – as the ordinary sparks for him provocative lessons that are applicable particularly to South Africans, but also to others the world over. Throughout numerous essays, his interests and intentions are regularly reiterated:

I set out to be provocative, posing rather than answering questions, to be exploratory rather than definitive. I did that not just to sound clever, but because I deeply believed in that kind of intellectual process. I believed in the relevance of that process to the reinvention of South African society through the intellect. (70)

Understandably, Ndebele’s work is steeped in South African history, for whether we acknowledge it or not, we live out its legacy daily. He is evidently well read, making reference to other respected philosophers such as Marx, Foucault and Aristotle. His discussion also reveals the influence of some of Africa’s most esteemed writers, such as Mofolo, Mphahlele and Coetzee. His collection of essays is marked also by a preoccupation with the importance of education, as well as the media and the arts. He often pleads the case of children as the future of our nation, and appeals particularly to present and future leaders in their responsibility to South Africans.

“We have been far more concerned in the new democracy with what to do than with how to do it,” Ndebele argues (11). Consequently, he takes it upon himself to engage in social commentary. His essays, though brief, produce clear, profound insights that resonate with the reader long after the fact. “It is this kind of understanding, I believe, that should be at the heart of a democracy such as ours which was intended, among other things, to thrive on thoughtful intervention,” says Ndebele. “This would be an antidote to orthodoxy and the comfort zones of populism” (11). This ideal is evident in his take-no-prisoners approach to South African leaders; and certainly he is not going to be dictated to by race or rank, as he challenges the likes of FW de Klerk, Magnus Malan, Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma. No South African is permitted to abdicate responsibility by blindly claiming to be a victim of circumstance; and Ndebele is exemplary as he steps up to wrestle the giants of disparity in the legions of black and white, rich and poor, leader and follower. From work ethic to corruption, hypocrisy to racism, the AIDS pandemic to the War on Terror, there seems no topic too intimidating for Ndebele to broach. Perhaps he simply has the guts to say what everyone else is thinking anyway, or would like to think; and in his forthrightness he reveals and deconstructs our assumptions and undermines our (often unconscious) prejudices.

He commonly does this by invoking wry humour, such as in one short story, “Game Lodges and Leisure Colonialists”, in which he deftly describes the dilemma of the black South African elite caught in the awkward “process of becoming” (99), uncertain as to how best to interact with the black working class. He is also successful in his courageous 1992 UCT graduation address, “A Call to Fellow Citizens”. His attempts at “freeing” (44) the white community from the damning confines of the racist National Party are communicated authentically and without patronisation. “Elections, Mountains and One Voter” is another poignant recollection of Ndebele’s participation in the 1994 election. Herein, once again, the ordinary sight of Table Mountain inspires an introspective account in which he makes himself vulnerable to his readers. In this very personal and mature revelation, he admits and confronts his own prejudices. Consider this unconventional and moving reflection on two white policemen raising the new South African flag:

They seemed lost. Yet, there they were, in the call of duty … My heart went out to them. I confirmed something else at that very moment: how much I had been socialised into the values of the struggle … So there were my two white policemen: I gave them my compassion, they protected me. (50-51)

In revealing his imperfection – his humanity – he endears himself to his readers and wins them over. Indeed, he appears to be that one kind of South African we all aspire to becoming, one who, in his frailty, we may actually have a hope of becoming.

Special mention must also be made of a particularly exceptional story, “The Year of the Dog”, which stands out from the rest of this collection with its explicit imagery and highly emotive language. Ndebele describes in graphic detail an imaginary scene in which a mob brutally beats and kills a dog. “But be warned,” Ndebele subsequently cautions us, “the reality around you can be as stark as the world of your imagination, sometimes surpassing it. Let me take you down memory lane …” (252). He proceeds to describe the South African abominations of the 1913 Land Act, the Pass Laws, the Bantustans, forced removals, the exploitation of blacks within white-controlled industry, Soweto in June 1976, and necklacing. “You can see how often we have treated people and things as if they were ‘just a dog’,” Ndebele concludes (253).

Then, in a bizarre inversion of events – one that is more funny-peculiar than funny-haha – Ndebele presents an almost farcical imaginary comedy in which we exhort the dog, redeeming it from its association with depravity. We respect the dog’s loyalty, companionship and playfulness. The parallel becomes serious as Ndebele reveals the dog as representative of anything of worth in South Africa – from women and children to the economy, to public property and so on. Yet most outstanding for me is not Ndebele’s obvious literary skill, but rather his response to the events from which the inspiration for the essay derives. After the acquittal of rape charges against Jacob Zuma in 2006, Zizi Kodwa, spokesperson for the ANC Youth League, called for “the dogs to be beaten until their owners and handlers emerge” (251). Ndebele’s name was one of four on a list of the so-called “dogs”. Instead of indignation and outrage, Ndebele responds with grace and empathy, emphasising not Kodwa’s shortcomings, but his lack of responsible mentorship. He says:

I like to think he yielded to the seductiveness of a thoughtless moment. I like to think of him as a well-meaning young person who erred … I would like to have a conversation with him, to reaffirm with him that our democracy is still about dialogue … I would like us to reaffirm our common commitment to a new and better society. (255-56)

Subsequently, in a by now unavoidable personal exercise in self-reflection, I find myself disconcerted by my positive review of Ndebele, here. Skeptical readers may find this hopelessly positive review difficult to swallow. At the risk of injuring my already precarious credibility, however, I would dare to venture that Ndebele will disarm and draw even the most skeptical reader in. Certainly he is not perfect, as he readily admits; nor is his polemical handling of matters definitive.

However, I believe my opinion has something to do with the following: absent from Ndebele’s account is a sense of bitterness, pride or lust for retribution. Contrary to the 80s and 90s trend of his contemporaries to write in a highly emotive and often accusatory style, Ndebele is level-headed and pragmatic. He says of himself: “I have a peculiar personal trait. It is that I tend to be at my calmest and most deliberate when some remarkable event has made everybody else excited” (49). Most refreshingly, in Fine Lines from the Box we find a sensible yet stirring appeal, a utilitarian petition, a visionary call to take mutual responsibility for a South Africa that seems almost within our grasp. Admittedly this may come as a surprise to some, given occasional misconceptions within the literary academy (after the first publication of his essay, “Rediscovery of the Ordinary”) that Ndebele sought to solidify the political-aesthetic divide.ii Yet, he says, in that very essay: “[T]he ordinary lives of people should be the direct focus of political interest because they constitute the very content of the struggle” (55). For Ndebele, within the South African context, the ordinary is inescapably political, and the political is inevitably ordinary. As such, all of Ndebele’s work expresses his concern with the social and political state of South Africa, even when only implicitly.

“I do not recall these events to embarrass or blame”, Ndebele assures us. “I recall these events as an occasion for serious reflection” (57).The quality of writing and thought, coupled with the author’s integrity, in Fine Lines from the Box, is such that perhaps it may one day be said of Ndebele (as he says of Archbishop Desmond Tutu in the article, “Moral Anchor”) that he has “left an indelible mark on the national character of South Africa” (82). At the very least it may be said that it is impossible to put down the book and remain unchanged. We must, as Derrida urged Americans in the wake of 9/11, be willing to take time to reflect – not only that, but to take subsequent responsibility for the shaping of our nation. May it no longer be possible to say of any aspect of the South African situation, as has been the case in the past: “A little more thought could have saved us” (11).

NOTES

i See, for example, “Phasing the Spring: Open Letter to Albie Sachs” by Eve Bertelsen, published in Pretexts 2 (2), 1990, or “Introduction” in Forced Landing by Mothobi Mutloatse, published by Ravan Press (1980).

ii Sam Tlhalo Raditlhalo describes this in greater detail in the Afterword of Fine Lines from the Box.

Works Cited

Ndebele, Njabulo S. 2007. Fine Lines From the Box: Further Thoughts about our Country. Compiled by Sam Tlhalo Raditlhalo. Cape Town: Umuzi.

_____. 1991. Rediscovery of the Ordinary. Johannesburg: Cosaw.

Simpson, David. 2006. 9/11: The Culture of Commemoration. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Outstanding description of fine work by a distinguished intellectual. I will get myself a copy.

Thanks for publishing this inspiring and captivating review! It declares this book a must-read for every thoughtful South African.