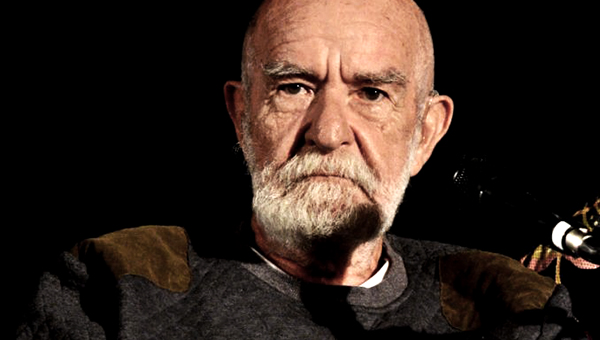

Athol Fugard 81. A conversation with Mannie Manim, 8 March 2013, US Woordfees, Stellenbosch.

Photo: Melt Myburgh

CLARISTA KOTZE and LEON DE KOCK

Unseasonal Cape summer rain envelops the Boektent at Woordfees. It’s a cozier shelter than it at first appears, and the atmosphere is unexpectedly personable. This state of affairs has a lot to do with the collective charisma of Athol Fugard and Mannie Manim as they settle comfortably into leather couches on stage.

At one point in their dialogue, Fugard presses his pipe to his chest, and with a sidelong glance and dancing eyes says to his friend, “it’s because I trust you Mannie … do you trust me?”

This is Fugard’s response to why, at the auditions for Die Laaste Karretjiegraf, he turned to the veteran theatre manager and lighting designer (Manim) rather than anyone else, to ask about a choice of actor: “What do you think, Mannie?”

The theme of trust recurs several times in the public conversation between these illustrious comrades of “committed” SA theatre, the kind that found much of its focus in witnessing the human degradation of apartheid. The packed audience in the large tent is keen. It includes Breyten Breytenbach and several other writers, not to mention prominent South African scholars and public figures.

At 81, Fugard talks crisply, clearly and movingly – in his sharply accented Eastern Cape style – about why trust is such an important facet in his way of making theatre. For him, a certain unexpected magic occurs when one establishes the kind of trust that allows actors to become, in a sense, co-creators of theatre. “I’ve always been very open to that,” he says.

Fugard recalls the late Yvonne Bryceland as an example of what deeply trusted – and trusting – actors can do on stage. He describes Bryceland’s unforgettable performances in his play Orestes when, at a climactic moment, Bryceland destroys a chair on stage bit by bit – and how she did this every night – for the entire duration of the run of this play in the early 1970s.

Both Fugard and Manim recall her “chilling, chilling, chilling” performance as Clytemnestra in Orestes. Bryceland would act out her relationship with the chair (representing her husband, Agamemnon), and then, at the climax of her performance, turn her passion into wrath, thrashing the chair to splinters with her bare hands.

Every night, they recall, the stage would be littered with bits of the destroyed chair.

Says Fugard: “I directed her to sit comfortably in the chair, to settle into it with sufficient ease and rest on it trustingly, that she would be able to find its one weak spot, feel that weak spot because she was so comfortable and trusting with the chair, and then, focusing on that single vulnerability, start weakening it joint by joint.”

Manim recalls how he and Fugard would drive into downtown Joburg every day to look for an “indestructible chair”, one that Bryceland would not be able to break.

They failed. Every night, Bryceland ferociously took that day’s chair apart, becoming Clytemnestra as she enacted her wrath upon Agamemnon while the Market Theatre audiences sat stunned, their breath stopped.

The play was based on the John Harris station bomb incident in the 1960s, an act of sabotage against the apartheid state by ARM (the so-called African Resistance Movement, which also seeded Nadine Gordimer’s key novella The Late Bourgeois World). According to Brian Astbury, founder of the legendary Space Theatre in Cape Town, “it all began with Orestes”.

Fugard and Bryceland’s connection is a profound and impressionable one. Because of the level of trust Fugard managed to forge with Bryceland, he had to be extremely careful, he says, not give in to the temptation to “mind-fuck” with her. The same applied to all the other actors with whom Fugard developed relationships of special trust over the years, including memorable figures such as John Kani, Winston Ntshona and Zakes Mokae.

Photo: Melt Myburgh

Manim and Fugard engaged and entertained the big Boektent audience for a fleeting 50 minutes. Both appeared to be relaxed – Fugard sipping heartily from a glass of red wine, confounding public statements many years ago that he had walked away from alcohol completely. Both seem entirely unaffected by success. Both are as sharp as bright new pins.

The matter of age was almost forgotten until Fugard himself flagged it. At 81, the great man still has an electrifying presence. His wit is still sharp, and his mind astute. It is a thrill to hear what language does in his mouth.

Fugard tells the audience that he doesn’t know how much time he has left, but that he “looks on [his] 80th year as the biggest mistake of [his] life”. The celebration of it, he explains, brought too much noise into his life, and for this reason he has decided to “disappear into the mists” of Nieu Bethesda, where he will assume“a long period of silence”.

He confesses that he is tired now, but he swears never to stop working. In fact, his first task is to continue with a new work of prose. He has found the perfect form, he says with almost childlike enthusiasm, for what he wants to say in this new work of prose. Fugard confesses that his one weakness in “playwrighting” (“wrighting”, he emphasises, like a carpenter making a well-made chair) is his tendency to narrativise via his characters. He has always, in this way, tended towards prose, and now he will indulge his prose yearning as he “disappears into the mists”.

Manim remembers a brand of red ink, resembling blood, in which Fugard once used to write. Fugard explains that the red pigment came from a berry he used to mix with a particular type of ink. The berry, it seems, has become extinct, and the company who produced the “special” ink has since disappeared.

Fugard has resigned himself to writing with black ink. “But this doesn’t mean that I don’t bleed anymore when I write, Manny.”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project