EVENT: Outsiders or Insiders? Galgut, Kunzru, Mukherjee and Heyns (Sunday, 25 September; Fugard Studio)

SEAN O'TOOLE

Damon Galgut, Hari Kunzru and Neel Mukherjee discuss whether their characters are classical outsiders or reflective of a disconnected majority. Chaired by Michiel Heyns.

There are two routes to the answer, I realise. But let me first pose the question. Why do writers feel compelled to speak about their work? It inevitably leads to entrapment.

During a recent presentation at the Goethe Institute in Johannesburg, writer and poet Antjie Krog asked this very question, from the ex post facto vantage of the stage, adding that artists and writers continually and voluntarily walk into this trap, a trap that demands of them that they augment with superfluous words the things they have created. She invoked the model of JM Coetzee, austere and largely silent, his completed texts his only response. This is one route to the answer then: silence. But, as the gregarious and self-mythologising German artist Joseph Beuys remarked of one of the 20th century’s most enduring iconoclasts, “The silence of [French artist] Marcel Duchamp is overrated.”

Silent they weren’t, literary asteroids Damon Galgut, Hari Kunzru and Neel Mukherjee each, in their own literate way, grafting a surplus of words onto their creations. Damon appeared the most hesitant and gauche in his prescribed role as self-reflexive arbiter of his own creative work. In a session that demanded of the three authors that they effectively become literary critics and assess whether their characters are “classical outsiders or reflective of a disconnected majority”, Damon started off by saying, “We are the last people who should have a take [on this]. It is a perception that comes from …” He didn’t finish the sentence. Perhaps the missing word is outside?

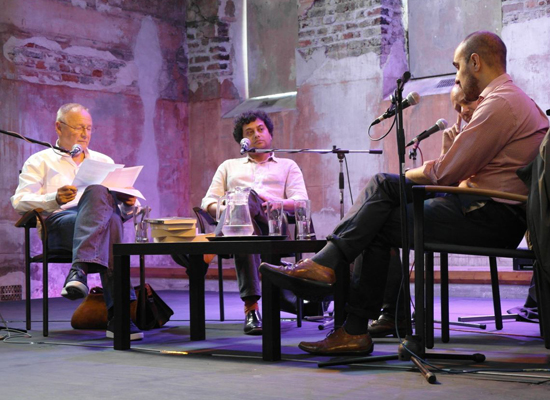

UNDER PRESSURE: From left, moderator Michiel Heyns, and authors Neel Mukherjee, Damon Galgut and Hari Kunzru.

Neel, who appreciatively quoted German philosopher Theodor Adorno’s dictum: “‘It is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home’”, went on to comment that Damon has embarked on a “sustained project” of portraying outsiders. Damon, who demurred answering an earlier question from author and moderator Michiel Heyns, was now quick to point out that he found Neel’s interpretation of his published corpus “startling”. “It is not a sustained project,” he emphasised. “I am just trying to express my own sensibilities.”

In his first foray into the discussion, Hari Kunzru speculated that the sense of character implied by the figure of the outsider is now a bit “shopworn”. Yes, agreed Michiel, who was tasked with gently doing the gear changing – but Michiel later offered that all three writers were working in the aftermath of the realist and picaresque traditions, an analysis accepted by Hari. “My first novel is picaresque,” said Hari of The Impressionist, published in 2003. “I like the idea of a character moving through a certain pageantry, which is what the English empire was.” By contrast, he described My Revolutions (2007) as a “more or less straightforward novel” that tried to explicate the motivations of a particular character. His current ambition is to deploy “gaps and silences to disrupt certain ways of doing plot”. After briefly discussing the Chilean writer Roberto Bolaño’s novel, 2666, he offered that his interest lay in facilitating the “eruption of something else that cannot be domesticated in the plot”.

Neel, who describes this process as the bringing together of two genres into a “frictive state”, remarked on how literary critics tend to employ their own shopworn analyses in accounting for the inexplicable dissonance this strategy allows into the novel. “Whenever anyone doesn’t want to do real thinking they trot out the term ‘magical realism,’” he offered. Neel, who tried, with varying degrees of success, to engage Damon as a sounding board, remarked on the “slippages” between the “I” and “he” pronouns used to identify the character Damon, the young traveller figure in his latest novel, In a Strange Room.

Damon was mercurial in his response, a manner that perhaps reflects his healthy ingestion of Samuel Beckett over the years. The real subject of In a Strange Room, he offered, was not the young man who travels to Lesotho and then further afield, but memory. “The present moment is a memory of what just happened.” If, unlike Coetzee, Damon is willing to entertain the opposite of silence – let’s call it volubility for the sake of exaggeration – his responses, at times acute and pained in their biographical honesty, neatly cut through the crap of being asked to perform a transparent or coherent self for an audience.

“It is amazing how in thrall we are to Aristotelian unity,” quipped Neel somewhere in the midst of Damon’s masterful act of delivery and denial. He was picking up on an idea tentatively birthed earlier in the conversation. “To be an adult,” said Hari, “one must be in mastery of oneself – and it is frightening when it is then taken away.” Later, he would add that to be a functional adult member of society required a measure of collusion in maintaining a variety of fictions. Damon, who offered French writer Albert Camus’s The Outsider as a bold exemplar of a novel that reverses this unity by slowly disassembling the fiction of coherence, said that the narrator’s abiding happiness at the end of the novel – “I was happy still” – was the product of seeing past “the consolation of the fictions of order”.

And, just like that, the hour was up. No questions from the floor.

CAPE TOWN IDOLS: Mervyn Sloman, far left, introduces the 'three best writers of fiction in the world', Neel Mukherjee, Damon Galgut and Hari Kunzru.

BRIEF RELIEF: From left, Mervyn Sloman, with cellphone, Neel Mukherjee, Damon Galgut and Hari Kunzru.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

Sean: Close-ups are rude indeed, and I appreciate your circumspection in this regard. I have come to dread public appearances where flashes go off in your face all the time, leaving me thinking oh-oh, I can just imagine what that one’s going to look like. Whic h is sort of relevant to your main point, about public exposure. The Loneliness of the Longwinded Writer? I don’t know. It’s an attractive idea, the romantic — and Romantic — view of the writer as the solitary creator. All I can say is that it doesn’t hold true for me, perhaps because I don’t have the self-discipline to lock myself up with my manuscript (to be honest, I don’t think I HAVE what you call ‘the discipline of being a writer’). So whereas there is indeed something stimulating about the ‘immediacy of performance’, in my case it’s not a function of my solitary existence as a writer. It may be something more ignoble, like liking to have an audience — at a slight remove, hence the rudeness of close-ups. But oh hell, I’m going around in circles here, because if we start unravelling (or unpacking, more fashionably) the shying away from close-ups, we arrive once again at the Damon mode, and its calling into question the whole, yes, intrusive business of author interviews (or performances).

I have just finished Rebecca Solnit’s wonderful book of essays, A Field Guide To Getting Lost. A remark in it struck me, particularly after reading your thoughts, Michiel. She talks of writing being a solitary pursuit, which is a self-evident insight; but then she goes on to contrast the loneliness of writing with the immediacy of performance, dance and music in particular. I’m wondering out loud here, and tempting to to do the same: do you think speaking in public, besides showing allegiance to the craft (and one’s publisher), isn’t also a way of broaching the loneliness, exile, solitariness – whatever the precise word – that forms part of the discipline of being a writer? (I don’t have the guts to be photographer: you’ll notice that I stole my shots of the four of you, not braving an introduction for an intrusive close-up. Then again, Auden said, ‘I think close-ups are rude.’ )

And I should have said earlier: your photos are great.

I think we agree that Damon’s response was both what made us sit upright, in its honesty, and made us wonder about a process that drags somebody on-stage to make such a personal statement. For myself, on balance, I cherish the memory.

Michiel: thanks for your measured and sanguine response to my question; also for pointing out that, while potentially fragment, like Emmantaler, the proposition has some holes in it. There was a moment, which I didn’t manage to record in my report, a moment that perhaps angled my thoughts: it happened when Damon spoke of his “ultimate inability to connect with other people, even when the desire to do so is there”. The statement made me sit bolt upright – typically I slouch – in response to its no-nonsense honesty. When I say honesty, I mean an honesty that one doesn’t anticipate while enjoying the waggishness – performance is perhaps a more neutral word – of clever writers saying smart things that made the R30 entrance fee seem insubstantial. (Yes, I happily paid to get in despite being the reporter.) A long-winded thank you.

Sean asks: Why do writers feel compelled to speak about their work?

The formulation is very finely gauged, implying, quite rightly to my mind, that most authors don’t really want to speak about their work; they feel compelled. Okay, so some are compelled by their own raging egos; but there are many who take to the stage quite reluctantly, if not all of them quite as reluctantly as Damon. So why do it?

In the first place, our publishers want us to do it, believing, rightly or wrongly, that it creates a ‘profile’ and profiles generate sales. And let’s face it, we are not averse to sales either.

And then: if you’re going to have a literary festival at all, you need live exhibits, and that means, for better or for worse, writers talking about their work — we’ve got nothing else to offer. So perhaps not have festivals at all? Interestingly, even the performance-shy JM Coetzee does attend festivals (he’s just been to Kingston), thereby implicitly lending his imprimatur to the institution, albeit on his own terms (he refuses to discuss his own work, though he’ll read from it). And Damon was very much part of Open Book, and agreed to be on a panel whose very subject signalled that it was going to dig into the authorial psyche. In the event, I, as coordinator, felt I was pushing the boundaries of decency in prompting Damon to rehearse in public what he had already done superbly in print: but there we all were and there was the audience and there was the subject, and somehow the mix had to produce a conversation — which I think it did, thanks in the first place to Neel’s persistence, and then to the magnanimous acceptance on the part of the other two of his challenge to openness. I think all three speakers were very generous in what they were prepared to share with the public, but Damon probably had to overcome a much greater temperamental resistance than the others. In his case, the ‘compulsion’ to speak about his own work was more a generous willingess, for the sake of the event, to subordinate his reticence to a public persona he had contracted to assume. So that may be another reason why authors speak about their work: a kind of loyalty to the craft.