EVENT: Moeletsi Mbeki: SA’s Tunisia Moment (Saturday, 24 September; Townhouse Mostert)

SEAN O'TOOLE

Moeletsi Mbeki discusses SA’s possible upcoming Tunisia Moment with Judge Dennis Davis.

Do intellectuals wear socks? Yes, it would seem, judging the foot traffic at the fest, but not so Moeletsi Mbeki, who forewent them for his talk with Judge Dennis Davis.

This casual note in an otherwise earnest getup – grey blazer, pinstripe shirt, mustard flannels – mirrored the serious-but-not tone of Mbeki’s talk. A general observation first: Mbeki delivers his thinking effortlessly, without resort to grandstanding. There is always a laughter soundtrack just around the corner, which is a relief, considering that his subject is the gloomy time ahead for South Africa. Politically, that is.

PRIME SEAT: Moeletsi Mbeki on stage

Responding to an opening question from Davis – whether Mbeki’s comparison of the exponential growth in service protests locally, to the Tunisian moment was simply hysterical or a valid analysis – the former president’s brother smiled. He promptly reframed Davis’s question, saying that at stake was the “question of change and opportunity”, which we should all look forward to. The only person who wasn’t looking forward to this, he added, was President Jacob Zuma, who Mbeki says probably imagines himself as Hosni Mubarak on a hospital stretcher. Cue laughter.

The candour of his attack and generally unscripted nature of the dialogue lent dynamism to the discussion. Both men assumed particular postures, Davis sometimes crunching up like Rodin’s ‘The thinker’ while listening, Mbeki gesticulating freely with both hands whenever he spoke.

“The reality is that we have very little power,” stated Mbeki, who believes our current electoral system, born of compromise, elects parties rather than people.

“Did we get the constitutional design wrong?” queried Davis.

“It was right for the time,” responded Mbeki, who favours a constituent system, “but that arrangement was of its time.”

The original framing of the electoral system, he explained, had to take into account a forcibly segregated populace living in homelands. With urban settlement patterns more defined and the third national census looming, it is necessary and possible to overhaul the current electoral system, which favours parties, not people.

Later, after Mbeki again referred to our present constitutional system’s “rigidities” and the threats these posed to our “democratic space”, Davis asked Mbeki if he wasn’t glorifying the concept of a representative system of governance, where people elect people. After all, the candidate system was a hallmark of Apartheid South Africa; it also allowed Tony Blair to go to war in Iraq. No, replied Mbeki emphatically, the two scenarios are not comparable. The system then favoured less than ten percent of the population.

Addressing Davis’s question of whether the implosion of the ruling party – imminent or not – might have dire consequences for the country, leading to violent and fragmented politics, Mbeki was once again emphatic: “I don’t think South Africa is a fragile society,” he said. It is a fallacy and a scare tactic, he offered, to suggest that putting pressure on the ANC will be bad for South Africa. He recalled the monolithic rule of South Africa by the National Party for much of the last century. He asked whether anyone remembered the day it imploded? It was at this point that Mbeki articulated ideas he would later contradict.

South African civil society, he said – a construct that includes industry, trade unions, academia and the media – is sufficiently robust to counter the idea that the collapse of the state would be inimical for the country’s future. He then slowly whittled away at the certainty of this proposition, much in the manner Mbeki accused the current government of whittling away “our democratic space” through vehicles like the controversial Access to Information Bill.

“The reality is that South Africa is de-industrialising,” said Mbeki. During the 1980s, nearly a third of our GDP came from manufacturing – it is now thirteen percent. “China is destroying the tyre industry in South Africa,” he offered, adding that the ANC-led government was not acting on this because of supranational ambitions (Security Council status and admission to membership of BRIC). What was earlier offered as a robust industry suddenly seemed tenuous, a situation exacerbated by what Mbeki painted as the significant and unchecked flight of capital to London in particular, via Zimbabwe.

That many of Mbeki’s assertions, delivered with an uncompromising sense of sticking it to the man, were unsubstantiated is to be expected. This was a debate, not a lecture. Necessarily, the conversation travelled the scenic route, passing a number of dorps – Bheki Cele in camouflage, a sign auguring the remilitarisation of the police; and towns – Zwelinzima Vavi and his bodyguards, the leader of Cosatu a marked man for his stance against corruption; before arriving at Polokwane – Julius Malema learns from Zuma how to be a demagogue, offered Mbeki.

For all the laughter his sometimes light-hearted forecasts evoked, Mbeki was unequivocal and serious in his analysis. Political structures need rehabilitation. Change is necessary.

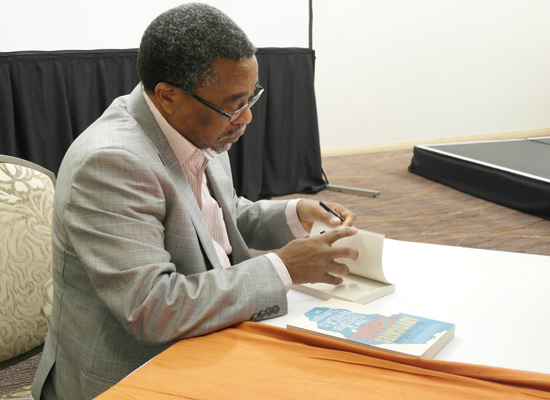

TAKE IT FROM ME: Moeletsi Mbeki signing a copy of "Advocates for Change: How to Overcome Africa’s Challenges".

A MAN OF THE PEOPLE: Moeletsi Mbeki engages with an audience member after his presentation.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project