EVENT: Wame Molefhe – Launch (Sunday, 25 September; Fugard Studio)

MANITZA KOTZE

Wame Molefhe, author of Go Tell the Sun, talks to Rustum Kozain.

The sun itself was in attendance at Wame Molefhe’s launch of Go Tell the Sun. The stage of the Fugard Theatre was fittingly bathed in natural light, a serendipitous celestial alignment.

Molefhe was joined by local poet and author Rustum Kozain, who also edited the collection of short stories, and who opened the session by giving his own views on the book. He liked Molefhe’s use of unadorned language, which got him thinking comparatively and contrastingly of Raymond Carver. However, where Carver’s characters are inevitably trapped in despair and oppression, Kozain found the narrators in Go Tell the Sun to be warm-blooded characters who aim to cure their pathologies by telling and disclosing their unsaid secrets.

He further declared that it would be disservice to Molefhe’s narratives to overdramatise them, and the tone of all ten stories in the collection is quiet; drama is downplayed and presented as coincidences. What might in other works be excessive catharsis is routine in Go Tell the Sun, thereby revealing its own deception, as the punches are delivered in unexpected ways and places, and the extremities of human experience become normalised.

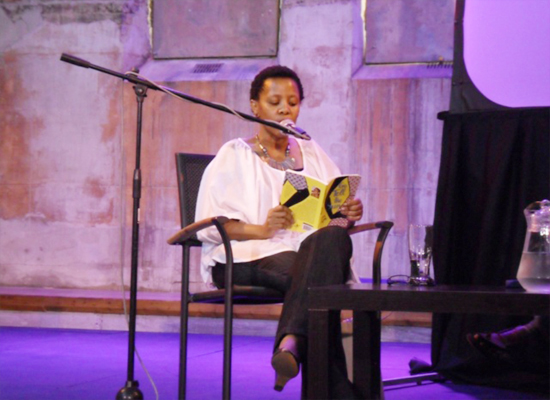

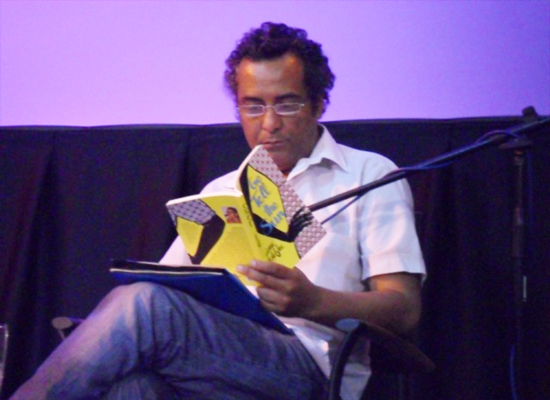

BATHED IN LIGHT: Wame Molefhe and Rustum Kozain deep in discussion.

Molefhe has been writing full time for three years, having previously studied microbiology and worked in an analytical laboratory, compelled to choose a career that society deemed appropriate for a “clever girl”. But she doesn’t view these years as wasted; rather, she considers them as aids to observation and analysis, in picking up the little things: “My microscopic eye helps pick out detail”. The curse of society inflicting its expectations on people, to conform, to obey, to submit, resounds both in Molefhe’s fiction and her life. She recalled an incident when she, as an enthusiastic thirteen-year-old, told her much loved and admired English teacher that she too wanted to become an English teacher. The teacher laughed at her, exclaiming that she “had to” become a doctor. That was, as Molefhe expressed, “how things were supposed to be”.

Go Tell the Sun’s ten short stories were launched in her native Botswana in February and positively reviewed in spite of the controversy that its taboo themes, including homosexuality, stirred up in a country where homosexuality is a criminal offence and where what one ought to do supersedes what one wishes to be.

Molefhe read two extracts from the story she described as her favourite in the collection, entitled ‘Botswana Rain’. The tale is of a young woman, Sethunya, reflecting on her childhood and love for her best friend, Kgomotso. The title refers to the unpredictability of this love, how Sethunya gives her love freely to Kgomotso, and then, without warning, withholds it as she tries to conform to society’s ideas of how a girl should behave. The extracts were flooded with phrases used by Sethunya’s mother of how girls “should” act, look and conduct themselves, and the oppressive and judgemental atmosphere and nature of the church she attended. The “shoulds” in the story even pertain to the weather, as reflected in the title.

BREAKING THE MOULD: Wame Molefhe reads an extract from ‘Go Tell the Sun’.

Sethunya, which means “flower”, or “bloom”, is the protagonist of all ten stories and, for Molefhe, illustrates what womanhood is, a gentleness that does not imply some kind of weakness of being. Sethunya is not a particular character, but ten different characters with the same name. She is representative of all Batswana women, a type of female archetype, but can be whatever she wants to be, a completely different person, if just a few details of her life can be changed.

PAGE TURNER: Rustum Kozain reads from ‘Go Tell the Sun’.

Molefhe’s own temperament comes to the fore when she writes, so she doesn’t feel anger at “the establishment”. She addresses social issues gently in her writing and tries to resolve them through means other than force. She examines society and addresses social issues but, even when society does not respond as she had hoped, Molefhe recognises the rules and regulations that people are taught and influence the way they think. She doesn’t judge her audience too harshly. She sympathises with her characters, who strike a delicate balance between their feelings and what they have been taught is the “right way” to behave. Their choices are not necessarily the best choices, often requiring them to deny themselves in order to survive, but they may enable them to find a sort of peace.

Writing is a space where Molefhe can do as she pleases and, yes, she revels in this freedom, constructing a society where she pays no heed to rules and regulations; where she can “hide behind the label of fiction”. However, she also said that “fiction is truer than the truth”. She enjoys the controversy surrounding her book in Botswana, but remarked that, for the most part, the issues relate to how autobiographical her characters are.

Kozain referred to a sentence in the first story in Go Tell the Sun, where the character of Sethunya says: “There and then I learned that deception is easier in my mother tongue”. This raises the question of whether Molefhe, writing in English, which is not her mother tongue, can deceive as easily in her fiction, or if her fiction is, as she stated earlier, “truer than the truth”.

A member of the audience concluded the session by responding that all language is translation – trying to find ways to distil the inner experience into words. If this is true, then Molefhe is not only a talented weaver of fiction that may, perhaps, be truer than the truth, but also a very skilled translator of this interior understanding.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project