Draw your life, publish your self, Franschoek Literary Festival, 11 May 2012.

KATE ELLIS-COLE

Mason, Davis, Opperman, Motshumi

Andy Mason looks like the surfer dude who never wanted to grow up. He sits behind the microphone at the presenters’ table, which is bedecked in starched white, wearing a T-shirt showing a cartoon surfer and his board. The T-shirt says “Wow” to the waves that have just parted before him.

The T-shirt may seem silly, but it’s the ideal image for our convenor. Andy Mason is one of South Africa’s few cartooning greats. Joining him at the main table in the Franschhoek Public Library for this afternoon’s event are Mogorosi Motshumi, Su Opperman and the currently invisible Andy Davis. Mason quips that Davis will appear when it’s his turn to present. And with the frivilous prayer: “Dear Lord, please help us with this presentation. Amen,” the Draw Your Life, Publish Your Self event gets into full swing.

The discussion, which advertised itself as a tutorial of sorts on autobiographical drawing and writing, comes across more as a series of autobiographies of the successful artists on show. Opening the conversation is Andy Mason himself. Bearded and bespectacled, with hair as white as the Silver Surfer’s board and gathered in a groovy ponytail, Mason looks like he should be the cult-leader of the group.

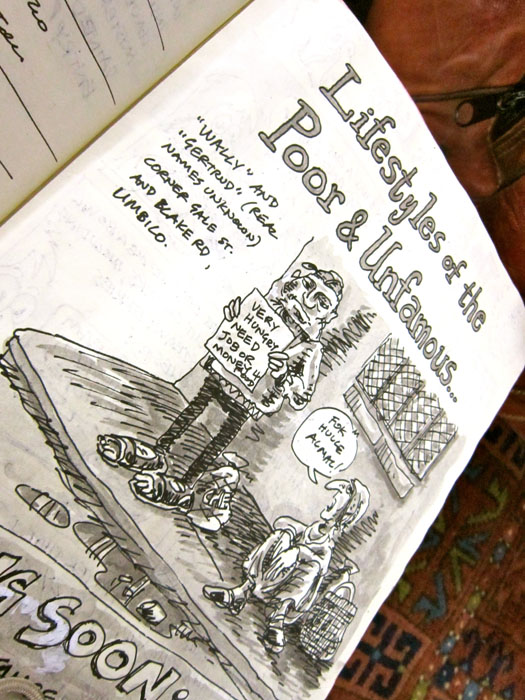

Mason insists that the place to begin drawing comics is autobiography, specifically with a daily graphic journal. (A selection of his own journals lie in a stack alongside him as he speaks.) Mason talks about his life as a cartoonist and writer, waxing lyrical about his love for Durban and surfer culture, which proves that his T-shirt is without doubt

Andy Mason

autobiographical. Mason may not be quite the maverick he dreamed of being, but he regales the audience with tales of his youth and how he “bunked work” to spend time tweaking the graphic journals he used to keep.

He tells of the conflicts he faced in pursuing his dream. “[Drawing] is a pretentious, self-interested narcissistic WANK!” accuses one of Mason’s alter-egos from a journal page. “Money talks, bullshit walks,” the antagonist continues, propelling Mason into a description of how hard it is to earn money as a cartoonist.

As a result of the difficulty of procuring publishers, Mason began working with collaborators. Comics he has published, such as “The Vittokes” – which is about a “washed up” old surfer – “Pax” and “The Big Chillum” all arose from personal experience and are in some way either autobiographical or social commentaries.

After introducing us to “Azaniamania”, Mason’s latest published work, he shifts the focus to showcase what he calls the “masterpieces of great graphic literature”. The list begins with legends such as Robert Crumb and wife Aline Komisky, and extends through the ages to South Africa, concluding with work by Cape Town comic Jessie Breytenbach, the Bitterkomix masterminds Kannemeyer and Botes, and the talented recluse from Muizenberg, Joe Daly.

Mason finishes his segment by lamenting that we “don’t have a proper comic community in this country”. He then reminds his audience that comics and cartoons were a “vigorous alternative press in SA” and a “big part of global anti-apartheid movement”, before inviting Mogorosi Motshumi to address the audience.

Motshumi and Mason are acquainted as a result of having worked together in the 1980s. “When Andy initially asked me to speak today, I said no problem,” says Motshumi. “When he called again to tell me I have 30 minutes for my presentation, I almost dropped dead! I’ve always told anyone who asks: I became an artist because I’ve never been able to express myself verbally.”

And yet express himself is what Motshumi does. Taking the audience gently by the hand, he guides us through the anecdotes and tragedies that form the collage of his life. We hear about his delightfully Methodist grandmother – the woman who raised him. Her strict prohibition against swearing was one of the things that pushed him to draw instead of speak, he jokes. He tells the tale of the time when someone insulted his grandmother, and so he beat the someone up. When he got home, he told his grandmother what had happened, “and she beat ME up”! The audience laughs.

Motshumi recounts the struggle years without emotion, candidly recalling the watershed moments in his life in his

Mogorosi Motshumi

deep, baritone voice without pausing to linger on any particular agonies. He describes everything from being fired to being burned, but concludes the tale with a candid disclosure that he now lives with AIDS.

Motshumi explains to the audience that Andy was the first person he told when he found out he was infected. “My story is actually Andy’s story,” he says. “He told me, ‘you were in the Struggle, and just when you think you’ve achieved something, you have to deal with the struggle of AIDS’.” And that’s what Motshumi’s latest venture, “360 degrees”, is all about.

“Andy told me people are living in a comfort zone and need to be taken out of it,” he declares. “So here I am.”

After a short intermission, Andy Mason welcomes Su Opperman to the microphone. Recently having obtained her Masters degree in Fine Arts at Stellenbosch University, Opperman’s style is worlds apart from Motshumi or Mason’s.

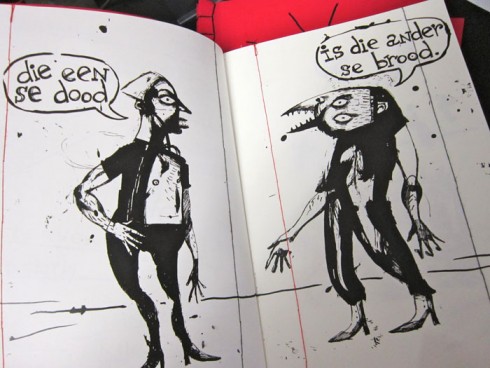

Her recently self-published graphic novel began as an artist’s book. The drawings, according to Opperman, are value orientations that turned into autobiographical content. She tells the story of her predeceased brother whom her parents lost prior to deciding to have her, and explains how the caption “Die een se dood is die ander se brood” relates to this.

To Opperman, the characters in her graphic novel are an act of remembrance as symbols manifest in characters, linking them to people she’s known. The comic is called “Gifpit”, and is supposed to be representative of an isolated community living in the Karoo. The story is dark and macabre, its humour acerbic, playing along the peripheries of life and magical realism.

For Opperman, to create art one “[has] to understand what you’re actually working with”. For her, her drawings and the narrative were a way to create new values in a post-apartheid world where the old Afrikaner culture had come to an end: “Afrikaans stereotypes are archetypes with their symbolism removed,” she says.

Opperman’s expressively scribbled black ink, paint, pencil and Tippex drawings are the work of a “lazy, spontaneous artist”. The drawings are abstract and quirky, the brushstrokes schizophrenic,

Su Opperman

as Opperman creates works that are unconstrained by format and freely translatable – a process that Opperman calls the “manipulation of myth”; it represents her own quest for knowledge and meaning.

Her advice? “The most amazing drawings come out of letting your hand roam, and with it your mind.”

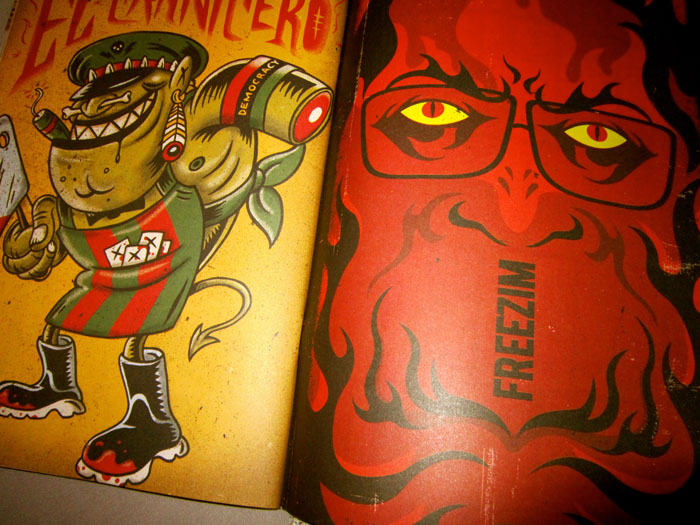

Andy Davis has by now recovered from his invisibility and sits at Andy Mason’s elbow, ready to begin his segment. He welcomes us to his “Journey of Self-Publishing - The Vanity Press” and tells the story of how he came to be the editor and director of Mahala.co.za, one of South Africa’s most popular online youth magazines.

“It may not have been the best idea, calling our magazine ‘free’,” he quips, explaining the risks and struggles associated with producing free online content. But he goes on to say he has always believed there should be no barriers, and accordingly joined forces with his friends to publish the stories in which they were interested.

Davis began his life in Johannesburg, and moved to Cape Town to pursue his studies. He puts up a slide featuring a photograph of J.M. Coetzee, saying that as his lecturer in the 1990s, the Nobel Prizewinner taught him “a thing or two” about writing.

After studying, Davis became editor of “SL” magazine. Following a massive dispute with his boss and the subsequent sale of the magazine, Davis moved back to Joburg. He and his friends began to distribute surfboards

Andy Davis

and wetsuits to underpriveleged kids interested in surfing, and registered the name “Mahala”.

After tough financial times, Davis got onto the internet. “If you’ve got something to say, it’s very easy to put up a blog – it’s simple really,” he tells his audience. “You have an audience as long as you keep people interested.”

Mahala has since become an important archive of emergent youth culture in South Africa. The fresh and exciting culture burgeoning in spaces like the Cape Flats and Soweto were maligned and going largely unreported, and this is where Mahala intervened.

It has not been an easy ride, he warns. “It’s important for creative people to do what they love, but the world is not designed for you to go out and be a maverick.” Davis displays a wry smile as he says this. “It’s why I’m bald. Before I began Mahala, I had shoulder-length thick hair, and a six pack!”

Although financial restraints have made things difficult for Mahala and its owners, Davis declares that the new aim is to “colonise Africa by Mahala!” He decries the fact that South Africans are better informed about the Dutch and the French than their neighbours on the rest of the African continent.

Furthermore, “we don’t want to hear about our continent’s culture from a disgruntled Yale grad in a baseball cap asking ‘Oh my god, is that voodoo?! Are you gonna eat that’?”

“If you want to do anything, the most important asset, especially if you want to be successful in shit like this, is persistence,” is his strongest piece of guidance to the audience.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project