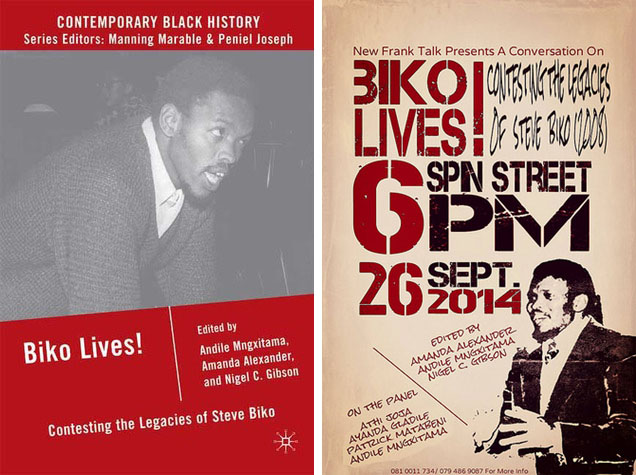

(Re)launch of Biko Lives!, Eds. Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander and Nigel Gibson, 26 September 2014, 6 Spin Street Restaurant, Cape Town.

WARWICK HENDRY

In his opening remarks at the (re)launch of Biko Lives! Athi Mongezeleli Joja referred to a renewed interest in the figure of Steve Biko. He situated the text amid a body of contemporary work on the issue and singled out a tendency toward what he termed the “biographical narrowing” of contemporary approaches. Biko, he argued, had been appropriated in the 90’s in the formation of what he termed a “cultural trope” which portrayed him as apolitical and which denied him the status of a thinker in his own right. In Biko Lives!, Joja asserted, Biko is treated as a philosopher for the very first time.

This public tussle over the legacy of Biko, so visible in the election campaigns of several political parties earlier this year, was the subject of some interesting analysis by the first speaker of the evening, Ayanda Gladile. It was part, he said, of a broader struggle – what he termed the “EFF’s historical liberation project” – which sought to produce a “revolutionary theory” on the basis of which a coherent “revolutionary program” might then be developed. It was a struggle against what he termed the ANC’s flirtation with white Marxists. It was an attempt to resituate race as the most urgent of the “inherent contradictions” faced by South Africans in the “moment of daily practice,” and in the effective formulation of the “theoretical elements of struggle contestations.”

The role of a reinvigorated Black Consciousness movement was the subject of Patrick Matabeni’s reflection on Biko Lives! Biko, he argued, offers us the opportunity to re-evaluate and to re-theorise a Marxian conception of social relations, “existential realities,” and “interpretive coordinates.” In another thinly-veiled swipe at the ANC and non-racialism, he cited Mbeki’s “I am an African” speech as an example of the manner in which Black Consciousness ideals had been corrupted. “White people,” he reminded the audience sagely, “are the enemy of Black Consciousness.” Following Fanon, he argued that the ANC’s policy of non-racialism has little to offer in terms of a solution to the problem of the “black outside of human space.”

In his closing remarks, Andile Mngxitama, EFF MP and co-editor of Biko Lives! chose to focus once more on the distinguishing features of the text. He characterised it as a reference text, a catalogue and a critique of Biko’s ideas as opposed to a mere biography. His talk was noteworthy for the fact that his own activities featured prominently. The message was clear: the EFF, in seeking to establish itself as an intellectual as well as a political power, had put down its roots into the deep and fertile ground of South African black radical thinking. This was not merely a struggle over the legacy of Biko’s ideas, but over the revolution itself. He spoke at some length on the “flattened racial hierarchy” that was the legacy of apartheid and which continued to be accepted uncritically by the ANC.

Mngxitama’s delivery was clumsy at times, and lacked the coherence and eloquence of his piece in the Mail & Guardian published the same day. He was actually heckled by an otherwise enthusiastic and receptive audience; both instances resulting from his handling of the issue of gender. Biko and gender, he admitted candidly, was “a silence that must be accounted for.” In elaborating upon his position, though, he drew the ire of several female members of the audience by suggesting that the three options available to black women were to “kill all black boys,” jail them, or castrate them. “Conditions in the ghetto,” he maintained, “are the creation of white society.”

Gender is clearly one of the biggest challenges facing the revival of the Black Consciousness Movement. If race is acknowledged once more as the primary contradiction, where does that leave gender? The all-male panel seemed ill-equipped to move beyond Mngxitama’s double-negative formulation: “there is nothing in Black Consciousness that is anti-women.” In an evening potentially marred by the late-arrival of two of the panellists and the unceremonious removal of an elderly white vagrant, the issue of gender violence proved to be the biggest flaw in the proceedings.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project