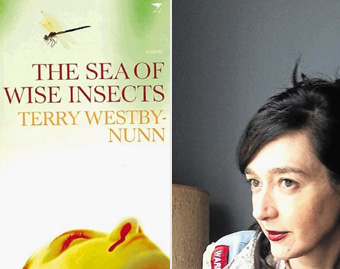

The Sea of Wise Insects by Terry Westby-Nunn, Jacana, Johannesburg, 2011.

This remarkable debut will probably be classified among the current wave of crime fiction washing over the country, but although it does indeed have a crime at its dark centre, it is much more than a crime thriller. Whereas the genre typically relies for its impact on plot and suspense, and characters are generally “types” who remain secondary to the plot, the fascination of The Sea of Wise Insects is elsewhere: the novel is really a meditation on human relationships, and how strange and unfathomable they can sometimes be.

One of Westby-Nunn’s many accomplishments in this novel is to create truly odd yet credible characters. The main one, Alice Wolfe, is introduced in the following way:

They say I am accident-prone. Ill-fated Alice who draws a dark little world of scars around her. My skin, a parchment of tales. Here I slipped through the wooden slats on a school holiday, there – that really long messy scar across my stomach – was when I was dragged out to sea by a freak rip and then just as suddenly, cast off, semi-conscious, onto the greedy rocks: grinning sharply as they gnawed my skin away.

I have always been unlucky. For several months I tried entering the lottery, but not a single number I selected ever came up. Not one. For a long time I suspected that fate hated me. Today, I am sure of it.

Today, Veronica died. (p. 2)

The novel adroitly switches between two main narrative threads: Cape Town, in the narrative present tense of the novel, which centres on an accident in which Alice’s sister-in-law-to-be (Veronica) is killed, and an earlier spell in London, where she worked as a housekeeper at the Tisca, a run-down hotel populated by weirdoes.

Alice gets the job at the hotel in the following way:

I’d applied to work at the hotel, after seeing an advert in a phone booth: “Hardworking woman wanted for various duties (chambermaid, kitchen, waitressing, front-of-house) in hotel in Hammersmith. Only quirky oddballs need apply. No straight-laced chancers or struggling artists please. Disabilities preferred.” I’d phoned immediately and Sophie had barked down the line: “What makes you think you’re so odd, then? Make it snappy and make it good, because I’m getting sick of these tedious calls.”

“Um, OK . . . Fate hates me. My body is riddled with scars – I’ve had 329 stitches. I’ve broken twenty-three bones – most in different accidents . . .”

She cut me off: “OK, stop whingeing. You’re hired. Get your arse down here on the double. It’s a live-in job. Twenty-five quid a day.” With that, she slammed down the phone. (p. 15–16)

This extract offers a glimpse of the rich texture of the novel as a whole: funny, fast-paced, quirky, dark, weird – and utterly compelling.

The wonderland Alice occupies is vertiginous and nightmarish, but, as is the case with the worst of nightmares, entirely believable. Alice meets Ralph at the hotel, and he follows her back to South Africa, all the while writing a hardboiled novel that gives the novel in which it is embedded its name. This is an extract from Ralph’s manuscript “The Sea of Wise Insects”, and it gives his view of the couple’s reunion in Cape Town:

She was waiting at the airport, eager to see him. Too eager for his liking. He was dependent on her now, he realised with horror. While he was happy to see that she was laughing and saying ridiculous things, like “How was your flight on the giant steel bird?”, another part of him was plotting escape from this dependency. She was now his devouring mother-creature, she had taken his mother’s place. She was going to be supporting him and smothering him with her eager love, and he hated it.

A chilling thought entered his head: maybe he could get hold of what little cash she had, and scatter her in a bath. (p. 159)

This last macabre notion echoes an earlier event, in which two of the characters in Ralph’s novel use a bath in which to dismember the body of a party girl who dies after taking a cocktail of drugs in their hotel room. Other details in “The Sea of Wise Insects" start to ring sickeningly true, and the reader, along with Alice, starts to wonder: is it an autobiographical novel in which Ralph faithfully recounts his experiences at the Tisca Hotel, including meeting Lucy/Alice? The Russian doll-like narrative structure of the novel is highly effective: the various layers talk to each other and haunt each other in equal measure.

Ralph does not act out his dark impulse, but he as good as kills Alice when he abandons her and leaves in his wake his manuscript, which discloses, among other ghastly revelations, that he has cynically been using her as inspiration. Ralph’s abrupt departure is part of the pattern of Alice’s luckless life. She was abandoned by her father as a child, and is openly loathed by her mother. And she is betrayed by her brother, for whom she covers up when the car accident in which Veronica is killed is investigated by the police.

There is a final betrayal, however, and it takes the form of a revelation that casts a lurid yet explanatory light on Alice’s profoundly dysfunctional family. It is this last detail that deftly pulls together the various threads of this complex yet highly readable novel and raises it from being merely engaging to being masterful and accomplished.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project