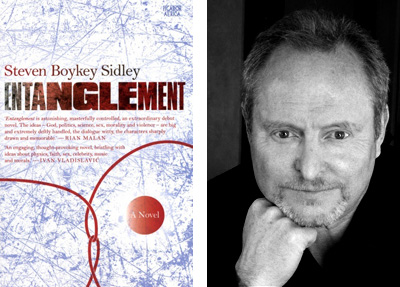

Entanglement by Steven Boykey Sidley, Johannesburg, Picador Africa, 2012

Steven Boykey Sidley’s debut novel, Entanglement, is an ambitious debut that aims to marry male mid-life issues with quantum physics, and morality with the mathematics of personal integrity. The author recently appeared at the Open Book Festival in Cape Town. He spoke about a lifelong desire to be a writer who started at school when his English teacher urged him to develop his writing talent. “It took me thirty-plus years to do this,” said Sidley, “but it’s not too late and I’m doing it now.”

His first book bears substantial endorsements on the cover and at the publisher’s website from a combination of highly regarded male literary figures. With or without the validation of “blurbs”, it is fair to hope that the characters’ struggle through conflict to resolution will be worth the investment of time. The sparse prose of the pithy first paragraph augurs well:

Professor Jared Borowitz sits on the stage in an auditorium. It is warm, summer stumbling in early. There is the usual sibilance from the audience, exuberance wrestling decorum.

No extra word in that. Not a spare punctuation mark either. An omniscient narrator allows the professor to recall how he once had faith in his teaching, but has recently shifted to a state where he “suffers classes heroically”. Suffering is good for a protagonist. It drives a story and demands development.

We do not yet see Jared, the tetchy physicist, facing any kind of heroic challenge. His inner commentary is conflicted. He thinks rather well of himself but is cognisant of having missed the “the brave new world of scientific celebrity”. As a reader, probing for a sense of how the scientist’s life will unravel, one wonders how he stomachs such awareness.

He ponders his relationship with his lover, Katherine, while waiting to deliver a graduation address. This attractive love of his life is a psychologist who gazes at him from the audience, manifesting her approval in a “half grin”. He notes with some self-satisfaction that he hasn’t cheated on her, as he did with his wife. He is reasonably sure she loves him and senses that, were she to cheat on him, he would magnanimously forgive her. Their relationship would survive.

Jared returns to contemplation about the recent shift in his mood. Why has he become such a “grouchy malcontent”? This becomes the central narrative as the story unfolds, but is not, in fact, the central drama. He presents himself as an enervated don, soon to retire, so it is a surprise when he discloses his age as mid-40s.

Awaiting his turn at the podium, he reflects on how he has been “graced … with sonorous voice, operatic projection, and the ability to drop long weighty pauses at exactly the intervals that are required to raise or release tension and expectation”. The seed of Jared’s conceit has been planted.

He abandons his prepared address and launches into an impromptu rant. His repetitious and stagy incantation against fools of every hue baffles one. It contains a long list of idiots who people the world: “Dictators, drunk drivers, genocidalists, tyrants, liars, useful idiots, fakirs, conspiracy theorists, homeopaths, wife abusers, child neglecters, supernaturalists, UFO-believers, card cheats, identity thieves, religious fundamentalists, white supremacists, movie queue jumpers, soothsayers, astrologists, robber barons, creationists and intelligent designers, rapists, history revisionsts, and so on.”

This says a lot about the professor, things he can’t begin to comprehend. The reader is now wondering about the logic that situates a homeopath and rapist in the same category, a card cheat and genocidalist in the same camp. Jared’s arrogance makes him a singularly unappealing protagonist. Is Sidley up to the challenge of the unlikeable narrator? How does the author ensure that his readers will stay the course to discover what happens to someone with whom they cannot empathise?

The psychologist’s response in the wake of his diatribe is telling. Jared returns to his seat and observes Katherine, who is “shaking her head, with both eyebrows arched dangerously, but she is also grinning slightly. He reckons that he will escape this one relatively unscathed.” Escape he does, and so does any potential dramatic unfolding.

The reader learns that Katherine refuses to join the extreme moral relativism debate that is Jared’s ideal intellectual standpoint. Her morality is “inviolable on the matter of right vs. wrong, good vs. evil, even inconsiderate vs. nice”. Despite this she does not unpick Jared’s hubristic defences. Were she to force him to unpack his inappropriate fury, the story might have been invested with the necessary conflict to compel readerly engagement. Katherine’s flippant response is: “Jesus, you were a barrel of laughs. How to turn a couple of hundred kids from happy to suicidal in 5 minutes.”

Does this mildness reflect a pointed disengagement from the relationship on her side? Is this where the tension will bloom, a deliberate device to advance the plot? Or does it represent too little first-hand experience of the more typically nuanced response of real-life psychologists? Some research can only be done face to face, after all.

Katherine becomes mildly more appealing when she tells her partner, albeit jokingly, that he is “a hypocritical dick”. The wry banter between them in the cafeteria after the address sets the tone for the relationship over the course of the entire book. The sameness of their speech doesn’t facilitate differentiation between their respective voices.

The sense that all is not well in Jared’s life grows, but the cause of his grumpiness remains vague. Is it a mid-life crisis? Burn out? Katherine is “worried” and chats to her girlfriends about him, but the dialogue between the women remains suspiciously shallow. No real suffering surfaces to propel the drama along.

The potential for real tension arrives when a gifted student, Cassie, visits Jared after his sanctimonious address. She challenges him, saying she consults a homeopath but that does not make her a fool. Will he fuck her, the reader wonders. Will she fragment his suave exterior? Potentially the most interesting character in the book, Cassie is shelving her scientific ambitions to become a rock star. She bids him goodbye and sallies off the page. Jared loses the opportunity to wrestle with his shadow.

All is not lost. Another possibility arrives for Jared to fully engage in the search for meaning. An email comes from his mentor, Derek Tomlinson, who is dying. Jared recalls how the elder scientist instilled in him the three-word injunction “Do the math”. This was as much a broad philosophy underpinning thoroughness of logic as it was a call to rigorous research.

When additional characters arrive, who are as glib and ironic as Jared and Katherine, one senses the novelist is in more trouble than his characters.

Bad boy literary figure Ryan, along with his coloured South African girlfriend Tam Tam, meet Jared and Katherine at a restaurant. The venue is described as “reflecting the short attention spans of the fashionable”. This is a disturbing sub-text. Instead of nuanced characters with discrete mannerisms and refined quests for meaning, the dramatis personae all seem to be blending into one. The gathering is plagued by an absence of real menace, as depicted in this extract:

The banter continues until the brightly costumed waitress arrives theatrically, bearing steaming plates of ostentatious combinations, whose proximity to real Asian food is tenuously pretended by rice and noodles, bravely accompanying chicken, beef, prawn and fish accessorised by startling confabulations of spices, herbs, nuts, chillis and exotic fruits.

Gone is the tight writing. Clichés and adverbs show a lack of faith in the reader. The plot rambles and red herrings appear. No identifying details locate the narrative specifically. The ubiquitous campus is probably in North America but the geography is an elusive Anywhereville.

Jared flies to London to see Derek one last time, hoping for an epiphany. His mentor recalls coveting the lovely Katherine and tells him, essentially, to lighten up. This anticlimactic faux enlightenment is followed by a violent encounter with a thug on the underground, which seems improbable and contrived. By this stage, one wonders if this is a male mid-life issue with which male readers will identify – or is it rather the case that the two-dimensional female characters might alienate women readers?

Take the brief appearances of Jared’s ex-wife and mother. The former has turned lesbian and marries a woman priest. The latter camps it up as the Yiddish Mama, fresh off the boat, but the purpose of this stereotype isn’t quite clear. Neither of these women can propel Jared into a crisis of faith. Nor can they offer him the kick in the tochas that might spur Jared into significant self-evaluation.

When Jared, Katherine, Ryan and Tam Tam go away for a weekend in the country with another couple, things turn truly peculiar. No foreshadowing sets the scene. No intensifying tension prepares the reader for a staggering and violent end. It arrives as if from nowhere. Too late to quit, one reads on with decreasing optimism that the glowing endorsements will ring true. The result is bewildering. Some readers just won’t get it. They’ll be left feeling cheated.

Is this a book for men about male identity? Or a nearly ready narrative that required somebody to “do the math”? Good editing – or good mentoring – could have improved this promising tale. Derek Tomlinson, Jared’s mentor, once said that "true science, at its most luminescent and muscular, was not for sissies and wimps”. The same holds true for the writer. Sidley, like Jared, needs to listen properly and respond to the challenge he faces. His next book is due out in 2013. Let’s hope it’s not too late and he is doing the math now.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project