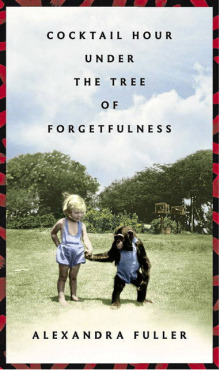

Cocktail Hour under the Tree of Forgetfulness by Alexandra Fuller, Random House 2011

Writing is an art, but it is not a martial art, as a memoirist once said. In her new book, Alexandra Fuller is quick with her punches – but is ready with a towel and some ice.

Part tribute, part satire, Cocktail Hour under the Tree of Forgetfulness is Fuller’s enlargement on her first offering, Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight, published in 2002. Her parents, Tim and Nicola Fuller, are survivors: of the loss of three children, of several regime changes, of each other.

During their almost half-century together, they have relocated to Kenya, Rhodesia, Malawi, Zambia. They are, physically and spiritually, frontier people: they have always Had a Farm in Africa.

During their almost half-century together, they have relocated to Kenya, Rhodesia, Malawi, Zambia. They are, physically and spiritually, frontier people: they have always Had a Farm in Africa.

The eponymous Tree of Forgetfulness is no nausea-inducing flight of fancy, either. As Mister Zulu explains to the Madam on the final pages of the memoir, all the headmen plant one in their kraals. “They say ancestors stay inside it. If there is some sickness or if you are troubled by spirits, then you sit under the Tree of Forgetfulness and your ancestors will assist you with whatever is wrong … [A]ll your troubles and arguments will be resolved.”

Alexandra Fuller is certainly troubled by spirits. That there is some sickness in her family – and that it mirrors the sickness of the continent – is a theme that preoccupies her. For one, she has already written a memoir of her unorthodox African childhood. For another, she is writing to shake off the shade of her mother – an impossible task while a parent is still alive.

In Cocktail Hour, the ancestors manifest themselves in the personages of both Fuller-the-author and Bobo-the-daughter. Fuller begins with an apologia: she reckons that her mother wanted someone in the family to be a scribe, a “pliable witness”. Through her representation in Literature, Nicola Fuller hopes to see herself made both heroic and whole. That Fuller herself fulfills this role is a conscious decision made in adulthood, although her grooming begins early. It is through Nicola’s agency – initially home-schooling her youngest daughter in the classics; nagging her into writing; correcting her first creative efforts – that Fuller becomes a writer at all. On these pages she stands (mostly) politely to one side, playing the straight man to her mother’s headline act. The schtick is deadpan, but both women must be acutely aware of its impact.

Nicola is a “broken, splendid, fierce” character who has stoutly buttressed the romantic ideas life generally beats out of us by the time we have our first jobs. She is the product of blood-thirsty Scottish forebears, bad-tempered heirs, and the black dog of depression circling the tea set: Edward Gorey in Africa. The Fullers (and the Huntingfords and the Macdonalds) are worth writing home about.

That studied posturing should not be under-rated: allegiance to The Stiff Upper Lip is what held the old colonials together when dysentery and disillusion took everything else. And it is what has stood Nicola Fuller in such good stead: pure will, manifest in her smile that is variously termed “ferocious,” "aggressive” and “terrifying” as she takes flying lessons, kills puff adders, dances on the bar.

Nicola tags her daughter’s celebrated literary efforts Awful Books, as if they are divorced from her entirely, while at the same time the narrative process mythologises her own story – a saga in the tradition of the Scandinavian myth cycles, with no guarantee of a happy ending. And “Nicola Fuller of Central Africa” has always wanted to be the kind of heroine in a Girl’s Own Adventure: an Earhart. She fancies herself the traveller who leaves home, surmounts obstacles, suffers drawbacks, but emerges, scarred and changed, victorious.

When real life intervenes with all its banality and trauma, she finds herself earthed by repeated losses (her homes, her children, her mind). “Mum” is now the persona who struggles with herself and with others, and who must negotiate the tension between personal freedom and personal safety. She tells and retells people her life story, stylising the episodes to keep the exploded fragments in some semblance of order. It’s an act of bravery, and it’s funny as hell, but it must have been hard to watch.

The madness that Nicola Fuller admits is safe and temporary, a genetic inheritance: “Highly strung, I think you mean. There’s nothing wrong with being that kind of bonkers. It has nothing to do with not being hugged enough and everything to do with being so well-bred, and that leads to chemical imbalance. We’re like difficult horses or snappy dogs; it’s not our fault. It’s in the blood.”

The madness that Alexandra Fuller examines is of a far more serious nature, one that requires medication and a brief period of institutionalisation. It is this kind that impresses both Bobo-the-daughter, who has to deal with a mother who is “at the end of a telescope”, and Fuller-the-writer, who notes that Nicola's sheer willpower returns her to her senses: “… [S]he forgave the world.”

But on this point her mother’s acid, self-conscious commentary prevails. “Of course I’m mad,” says Nicola cheerfully. As in the rest of the book, serious things are a joke – and a joke is a serious thing.

Similarly, Fuller wisely omits the truly horrible features of the “bush war” in Zimbabwe as well as the death of her sister (both already plumbed more productively in Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight). Too many squeam-inducing details provide realism but they also appeal to a particular type of reader – the rubber-necking smartvraat, who likes a good wallow at someone else’s expense but resists learning anything useful from the process. That Cocktail Hour is excoriating but also entertaining and enlightening is testament to Fuller’s own stubbornness and resilience.

It is also testament to her considerable talent, her comic timing, and her sheer bloody way with words. The juxtaposition of the hyper-real with the surreal at work in this memoir is what Fuller is best at: elegiac documentary in the style of Chatwin. She writes as her mother speaks: each is the master of the seemingly offhand remark that is a marvel of British understatement.

The memoir is imbued with the nostalgia idiosyncratic of the genre, with the poetry attached to the yearning for a world that never was. We can picture Fuller at home in Wyoming, puzzling over her youth and the devils she knew. It is, however, annoying to think that the book has been written mainly for overseas audiences, dwelling over-long on African pastoral scenes. There’s only so much wing-clapping of doves in a purple dusk that a native reader can take. Once it’s documented, the magic disappears. Otherwise, the book is fast-paced, seductive, shocking. It is meant to be all these things, and Fuller pulls off a compulsive read with journalistic accuracy, kindness and flair.

Nicola and Tim Fuller live now in a Zambian Valhalla, profitably farming fish and bananas, drinking cocktails against their African sunset. Alexandra Fuller has marked herself out as the recording angel of the family’s tragedy and romance: the very opposite of forgetfulness. Whether all its arguments and troubles are resolved is moot. Memory is fallible, as she points out in a chapter about a fancy dress party that the siblings remember very differently, and so the memoir itself is a struggle between mother and daughter for the last word: a perennial Awful Book. An exchange near the end sums up their competing attitudes. “What if we had been thinking straight? What if the setting of our lives had been more ordinary? What if we’d tempered passion with caution?”

“‘What-ifs are boring and pointless,’ Mum says… ‘Much better to face the truth, pull up your socks and get on with whatever comes next.’”

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project