13th Steve Biko Memorial Lecture, Jameson Hall, University of Cape Town, 12 September 2012.

WAMUWI MBAO

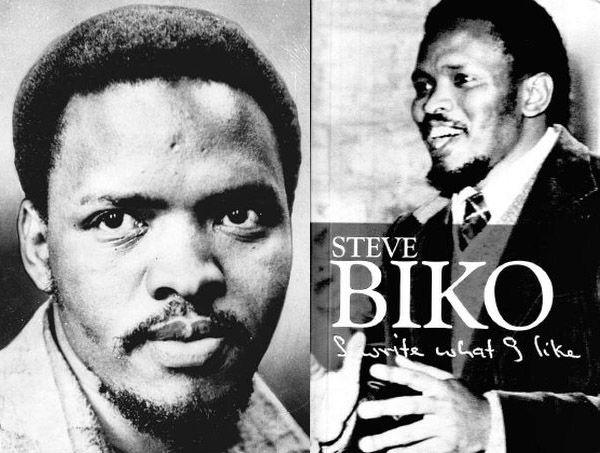

Pictures by SLiPnet photographer Retha Ferguson

The Steve Biko Memorial lectures are performances of public wisdom, testimonies in tribute to Steve Biko which take place every year in commemoration of the day the black consciousness hero died in police custody. Previous keynote speakers have included figures like Mamphela Ramphele, Njabulo Ndebele, Presidents Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki, and Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu. These figures have all exercised public thought before an audience, speaking on subjects that reverberate through Biko’s ideas and expand the history and legacy of his role as an intellectual in society.

This year’s event was held, as per usual, in University of Cape Town’s Jameson Hall. The public converged on the steps leading up to the hall well before the time, with tickets being sold out, much to the disappointment of those who hadn’t pre-booked. Television cameras trailed cables to catch out the unwary as the doors opened to admit the thronging crowds. The Cape Town-based marimba band ama-Ambush played the audience into their seats, with ministers Trevor Manuel and Deputy Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development Andries Nel numbering among the crowd.

The lecture is delivered on this occasion by Nigerian poet and novelist Ben Okri. Okri, also a professor of literature, is one of the world’s leading writers, and his list of accomplishments runs several pages deep. He has published ten novels, winning the Booker Prize for The Famished Road in 1991, and his latest work, 2011’s A Time for New Dreams, is an innovative collection of poetically articulated essays which are intellectually daring in form and content.

Okri is joined on stage by UCT vice-chancellor Max Price, and Steve Biko foundation CEO Nkosinathi Biko. Behind them, Steve Biko’s silk-screened face looks out from two large posters. Price welcomes all present to what will be the thirteenth Steve Biko Memorial lecture, noting that the university considers it a privilege to have worked so closely with the Biko family over the years in the process of running the lecture series. He speaks of the difficulty faced by the Biko Foundation each year in its task of selecting an appropriate speaker who can capture something of the memory of Steve Biko and do justice to his legacy. Such a speaker, Price intones, has to be someone capable of drawing a crowd, and someone who will have a message s/he can bring across to the public.

“I think we’ve been deeply successful over the last years,” Price says, giving tribute to the famous speakers who have contributed their thoughts to the memorial lectures.

It’s interesting to note the transnational dimension of these lectures: in addition to Zakes Mda and others, Price cites Chinua Achebe and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o as intellectuals who have stepped up to the lectern to perform public orature under the aegis of the Steve Biko Memorial Lecture series.

“All of them,” Price notes, “have inspired us, and rejuvenated us”, commenting that the lectures have become the flagship of the Biko Foundation, as well as one of the university’s flagship public lectures. “Today commemorates [Biko’s] life, and his tragic death in custody, on this day, 12 September 1977, through a celebration of the courage and the leadership of his political acts.”

Price stresses that the people gathered are honouring an intellectual whose courage was embodied in his ideas, through his writing and through his philosophical contribution to black consciousness. From this philosophy, Price says, “we take messages relating to the value of the university, and to the attributes that we would like our graduates to apply while they are students here at UCT.”

Price acknowledges Biko’s immense contribution “to social justice, to activism, active citizenry, and to leadership.” He praises Biko for promoting a philosophy or an approach to life that says “ideas matter”, emphasising how important such a philosophy is to the constituting of a university as a corpus of intellectual thought.

At this point, Dr Price hands over to Nkosinathi Biko, who elaborates eloquently on the subject of these lectures. “Today,” Biko commences, “marks the 35th anniversary of the murder of black consciousness Leader Bantu Steven Biko.” Biko tells us that his father died from a subarachnoid haemorrhage sustained during a violent interrogation in Room 619 at the Sanlam Building in Port Elizabeth.

Biko posits that what is more malicious than the torture and death of his father and other activists in detention, is the patently false excuses given by the security police, often with the complicity of health officials and the judiciary. He cites the notorious findings of Magistrate Prins in the subsequent Commission of Inquiry – “No one to blame” – a phrase Advocate George Bizos later used as the title for his book on torture and detention.

Biko reminds the audience of the content of last year’s lecture, delivered by Sydney Kentridge, the great advocate who represented the Biko family at the official inquest. “In the decades since Biko’s death, September 12 has become a rallying point for many communities around the world,” Biko adds. He notes that a number of institutions have been instrumental in shifting the focus, befittingly, from the circumstances surrounding Steve Biko’s death to an appreciation of the essence of Biko’s work. Biko’s challenge, his son avers, was the goal of bestowing upon South Africa, “a more human face”.

Biko tells us that although Steve Biko’s message is grounded in South Africa, it generates resonances with other locations that are still struggling with the residue of racism. Here, he highlights the diverse roles played by organisations like the Steve Biko Cultural Institute in locations such as Brazil and the Steve Biko Housing Association in England. He hails the Biko Foundation’s work locally with Wits and UCT, and details the recent accomplishments of the Foundation as he builds up to the conclusion of his doxology.

It’s Okri’s first time in South Africa, and when Nkosinathi Biko welcomes him on behalf of the Biko Foundation, a round of applause spontaneously fills the hall. Biko emphasises the timeliness of Okri’s arrival, coming so soon after events that have tested the maturity of South Africa’s democracy. He alludes here to the “Spear” debates that have shaken the country, asserting gravely that “the constitution was inadequate in providing a common ground”. He suggests that Okri’s work “challenges us to reckon with the limitations of the physical world”.

Biko proposes that Okri’s writing continues to remind us that in 1994 “it was not in the world of the physical that we found that gem that took us forward: it was, in fact, in the world of the intangible . . . we named it ‘Ubuntu, and that’s what took us forward’.” On that note, he hands back to Price, who formally introduces Ben Okri, noting that he has been compared favourably with writers like Salman Rushdie and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Price’s opening gambit dips into Okri’s Wikipedia entry at times, but he accurately captures the aleatory dimension of Okri’s literature.

Okri takes the lectern, looking like an art curator in his black beret and frameless spectacles. “Molweni!” Okri booms from the stage in greeting, prompting the crowd to reply with similar élan. Describing it as “a magical honour” to be invited to speak before the Cape Town crowd, Okri lays his manifesto before the gathered audience in a stirring, oracular voice: “Biko and the Tough Alchemy of Africa”, a title he admits to having improvised a few minutes before coming on stage.

He begins what will be a five-part speech by sketching out his engagement with the South African story. Okri tells us that South Africa’s great struggle and its history has been “the background music to our lives”. He affirms the transcendent nature of the struggle against apartheid, asserting that the South African struggle highlighted the meaning of justice for those all over the continent.

“As a child growing up just after independence in Nigeria,” Okri declares, “one of the first moral questions in the world was posed to me by your circumstance; that there were countries in which it was enshrined that one race was inferior to another, and that one race can dehumanise another, posed – to me – questions that went right to the very route of existence.”

Okri notes the horizon of events that shaped South Africa’s struggle, adding that incidents like Sharpeville, “with its unforgettable images” that “seared itself into the consciousness of the world”, was one of those world events that instantly made him aware of the interlinking fates of all on the African continent. “We suffered with you in your sufferings, and willed you on in your struggles.”

The first section of Okri’s lecture elaborates his views on the ethics of those who bear witness to history. “Sometimes,” Okri says, stressing his point with a raised hand, “it seems that awful things in history happen to compel us to achieve the impossible, to challenge our idea of humanity.” Okri emphasises that the struggle echoes in the historic consciousness of the world, posing the biggest questions facing humanity today.

Okri insists that these questions remain unanswered: “Are human beings really equal? Is justice fundamental to humanity? Or is justice a matter of law? Is there evil? Can different races really live together? Is love unreal, in human affairs? Why is there so much suffering? Why do some people seem to suffer more than others? Can the will of a people overcome great injustice?”

These questions, a manifold list that echoes through the hall, are described by Okri as “a nagging kind of music” that resonated everywhere humans turned their faces towards suffering. “Among the voices that articulated a profoundly bold and clear response to these big questions of fate, injustice and destiny – one whose voice pierced our minds – was the voice of Steve Biko.”

Okri proposes that one of his points of affinity with Biko is with the latter’s rigour, his high expectations of the human and the African spirit. According to Okri, Biko asks fundamental questions: “Who are you? What are you? Are you what others say you are? What is your selfhood?” These are questions, Okri professes, which will be relevant in hundreds of years’ time.

Okri’s delivery is spellbinding – he has the audience nodding along in hypnotic agreement as he lingers over particular words, immersing the audience in their depths briefly before moving on. His words run rich with meaning as he relates the immense impossibility of comprehending apartheid, a time which he feared would continue without end, “an unalterable fact like fate, or the moon, or hunger”. But with the country’s miraculous awakening, new questions occur. Okri gives this dilemma a framing question: “The nightmare is over, but what do we do with the day?”

As Okri sees, it, “we need to reincarnate Biko’s rigour”, his visionary self-sufficiency and his forensic questioning of society and all of its assumptions. “We need to keep alive Biko’s fierce and compassionate truthfulness,” submits Okri, adding that we may need Biko’s spirit more than ever. Biko, Okri proposes, might ask deeply searching questions about the state of affairs in South Africa.

“He might have expressed concern,” Okri soberly suggests, “about the police reaction to the striking miners of Marikana. He would have said that it does not need to be said that the murders, and the use of apartheid laws to try the miners, are shocking to the international community, and that it has disturbing resonances with his own death.” Biko remains for us perpetually poised in the stance of the difficult questions he posed.

Okri’s lecture is a captivating bricolage of ideas, with allusions to Kafka and Shakespeare mixing seamlessly with formulations on black consciousness as he develops and expounds on the far-reaching ramifications of Biko’s thought. “Biko,” Okri impresses upon the audience, “transcends politics and has within himself something of the terrible integrity of the true artist, one who will relentlessly pursue his vision of exalted truth, regardless of the consequences.”

The hour is not singularly given over to the idea of Biko as a man. Okri also ventures into questions on what Biko’s ideas say to our current time, and the time that is yet to come. Okri articulates a profoundly pan-African vision, one which discerns in the present state of Africa a malaise that requires healing through “the dream of vision”.

The reality of freedom is something that, in Okri’s words, “demands more consistency, vision, courage and practical love than was suspected in the unreality of injustice”. Resonating with the metaphorics of the TRC, Okri proffers that “what defines a society is not how it overcomes its night, but what it does with the long ever-after days of sunlight”.

He builds a counter-argument into the point he is moving towards, the recurring enjambment of his “some will say” sequence resonating in an Obama-esque manner. “Some will say that we emerged from the night with our hands tied, and that the sunlight still has a lot of night in it, and that the terms of our freedom and the context of our independence put lead weights on our feet, in a field where others have been running with free feet – and machine-assisted feet – for hundreds of years, before we entered this strange game.” Okri pauses, and the crowd bursts into ardent applause, clearly being moved by the force of his orature.

“These things may or may not be true,” he continues, arriving at what was surely the strongest of many salient points in this lecture. “What is true, is that no one will hand us the destiny that we want.” The applause is sustained and rapturous. Okri suggests that if anything, freedom is merely the overture in a much larger act, a minor part of a narrative whose real story begins with what those who are freed do with their freedom.

In an hour of speaking, Okri crosses from sea to shining sea, unmoored yet confident in the breadth of his reading of Biko, discussing the problems Africa has faced, its setbacks and its successes and all that lies between and beyond. His knowledge becomes a visiting place in which those present discover new qualities in those details of Biko’s written life we thought we knew.

As he descends towards his closing remarks, Okri reminds us that we cannot be passive about the single most important thing that affects us, namely the running of our lives. Here, he connects this idea to the core of black consciousness in the movement’s demand that people live in wakeful vigilance: “The leaders that you have say something about the kind of people that you are”, Okri states. “Black consciousness is an injunction to greatness,” he says.

His final words are an exalting call: “Pass the word on,” he intones, “pass the word along the five great rivers of Africa, from the Cape of Wise Hope, along the sinuous mountains, to the tranquil savannahs. Pass on the word that there are three Africas: the one that we see every day, the one that ‘they’ write about, and the real, magical Africa that we don’t see, unfolding through all the difficulties of our time, like a quiet miracle.”

These words carry an almost incommunicable weight as they echo through Jameson Hall. Okri ends with a line from his poem ‘Turn On Your Light’: “Our future is greater than our past.” As he steps down from the lectern the hall gives him a standing ovation.

You can download the transcript of Okri's speech here.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

As Okri sees, it, “we need to reincarnate Biko’s rigour”, his visionary self-sufficiency and his forensic questioning of society and all of its assumptions. “We need to keep alive Biko’s fierce and compassionate truthfulness,” submits Okri, adding that we may need Biko’s spirit more than ever. Biko, Okri proposes, might ask deeply searching questions about the state of affairs in South Africa.

Where are the young leaders of today. with some of Biko’s courage, insight and integrity, and with a willingness to ask the hard questions? Into the vaccuum comes Juju!

The man has the Mind of a Genius and a Heart of a Prophet – i feel inspired to do more, to learn, to keep an open heart and most importantly to believe in the good in others – i exist i belong i’m a reflection of those who came before me and as i step into the future i represent those to come and indeed i’m an African. AMANDLA

i have been in love with Prof Okri from 1998! I have used his teachings in all my work over the years. i thought he was an old man based on his wisdom. i was pleasantly impressed by the fact that he is a young dish with an old soul! his words and teachings invoke a sense of pride and self-respect. i missed the Steve Biko lecture, but listened on the podcast. Prof Okri, you are a genius!!!!!! Oga, thank you for your commitment to reawakening African pride and love of self.

Tiger