Nigeria Writes, 24 September 2012, Fugard Studio

WANJIRU KOINANGE

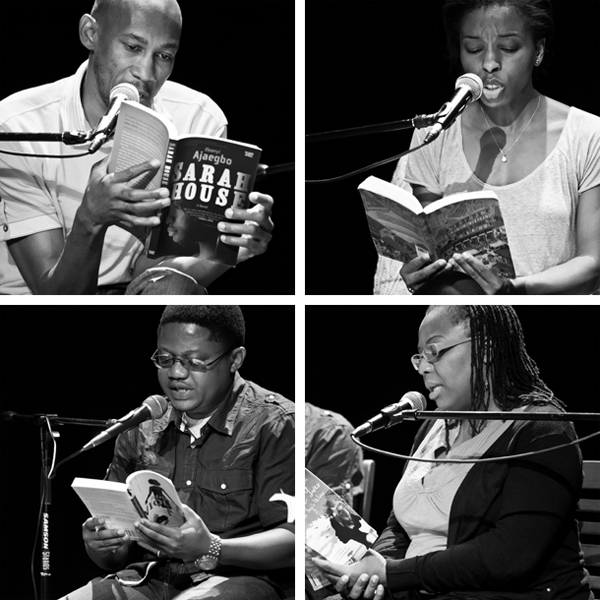

Clockwise from top left: Ifeanyi Ajaegbo, Noo Saro-Wiwa, Lola Shoneyin and Rotimi Babatunde

There was a palpable sense of camaraderie among the writers who graced the stage for “Nigeria Writes”, one of the events which drew this year’s Open Book Festival to a close.

The session, chaired by Yewande Omotoso, author of Bom Boy – which was shortlisted for the 2012 Sunday Times Literary Award – began with readings.

Ifeanyi Ajaegbo read from his recently published novel, Sarah’s House, which follows the life of a slave girl lured into prostitution. What struck me about Ajaegbo’s writing is how delicately he describes this character’s struggle as a woman.

Noo Saro-Wiwa shared an excerpt from her work Looking for Transwonderland – also newly published – which she wrote in a bid to come to terms with a country that failed her. (Noo’s father, political activist and writer Ken Saro-Wiwa, was executed in Nigeria in 1995.)

Rotimi Babatunde, winner of the 2012 Caine Prize, read from Bombay Republic, a story about Nigerian Soldiers who fought in World War II.

Lola Shoneyin, who provided most of the humour at this session, read from her novel The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives.

If the topics covered in these readings are anything to go by, then it is clear that Nigeria is a country bursting with stories to tell. It is probably for this reason that the panelists had a bit of a struggle narrowing down what they would describe as “the Nigerian Story” – that single event or period of time that all Nigerians identify as their “story”.

From left to right: Yewande Omotoso, Ifeanyi Ajaegbo, Noo Saro-Wiwa, Rotimi Babatunde and Lola Shoneyin

For Ajaegbo, the Nigerian story is one of poor governance, while for Shoneyin, referred to fondly by the panellists as “Aunty Lola”, the civil war would make a better fit. In the end it was agreed that the Nigerian story can be described only as the story about the local and the national experience – about those things that happen all over the world, but in a uniquely Nigerian way.

Omotoso explored the problem of a label such as “Nigerian Writers”, and the way in which critics try to pigeonhole the work of writers who come from a certain place in the world. Shoneyin, however, chooses to wear this label with pride, because it suggests a history of great writing that spans generations – a literary history that not many Africans can claim to possess.

“Also,” she adds, “Ghanaians can’t write!” – and the audience erupts into laughter. Saro-Wiwa has no problem calling herself a Nigerian writer because, she says, her stories are rooted in Nigeria, as she herself is. Babatunde says the label “African Writers” seems to be especially problematic because “African Writing” is not a genre.

The writers are asked to defend their decisions to write in English despite living in a country with more than 293 languages. Shoneyin responds by saying there has never been any doubt in her mind that she should write in English, despite it being a language imposed on Nigerians, which is also the case in many other former British colonies.

English is the language which unified Nigerians, the lingua franca that enables them to have a conversation. However, Shoneyin avers, it is important for every African or non-English speaking writer to use English in the way that suits them; they must infuse the language with the colour of their indigenous languages.

The session on Nigerian Writing was a lively one as the panelists agreed, and agreed to disagree, on several of the topics under discussion. However, there was general consensus on the need for more collaboration between Nigeria and South Africa – and that this should go beyond the infamous visa wars. The writers all said they had grown up reading works by South African authors, both in and out of the classroom. However, the relationship between writers from both countries had seemingly withered over the past two decades, and this was a connection that needed to be rekindled - quickly.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project