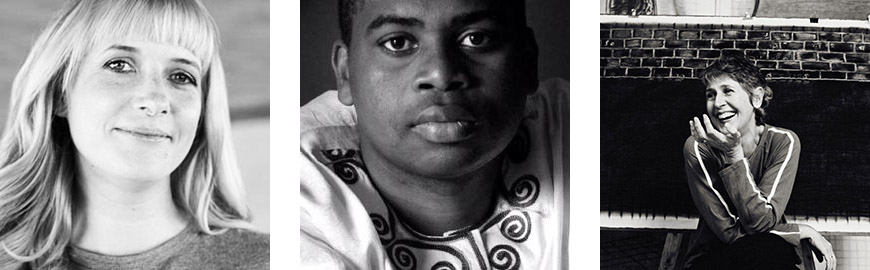

Three South African authors have made an impression on me over the past few years: Ingrid Winterbach, Lauren Beukes and Nthikeng Mohlele.

Ingrid Winterbach’s oeuvre has become something of a South African encyclopaedia, and traces Afrikaner history – but also other kinds of histories such as evolution and linguistics – through thematic recurrences of loss and trauma which are often narrated with an almost carnivalesque humour. But despite numerous accolades within the Afrikaans community, Ingrid Winterbach remains largely unread by English-speaking South Africans. I have to wonder why this is and whether there remains a bias towards all Afrikaners due to Apartheid or whether this is part of a larger socio-political reason. Or even whether it is because of a dwindling reader culture. Whatever the reason, it’s a sad state of affairs.

Then we have Lauren Beukes. Unlike Winterbach’s language-driven novels, Beukes’s gutsy plot-driven cityscapes deal with intersected worlds-within-worlds. And of course she’s very widely read; both within and outside of our borders. That, at least, is something. Yet it does also say something about the domination of English. Often reminiscent of comic books, her novels have a juxtaposed picturesque quality to them which – at least for me – creates immediacy and reading-urgency. Beukes’s novels are Alice-type trips into her mind’s wonderland and I can’t wait to see what’s next.

Nthikeng Mohlele is the third author whose novels I have come to love. I first heard him speak at last year’s Open Book Festival and was struck by his humility and quiet insight. I felt I had to read him and immediately bought his second novel, Small Things. Textured with smells, sights, music and beautiful narrative imagination, this novel became a fast favourite in my collection and I soon went looking for his first novel, The Scent of Bliss. Although Mohlele writes in English he, like Winterbach, remains a relatively unknown author and again I have to wonder why this is and whether this says something about the divides of our country which, under a thin veneer of rainbow rhetoric, remain largely as they were. I can only hope to be wrong.

But enough of my musings. What is more important is the work these novelists are doing. I recently caught up with each of them to find out what they’re up to and what we might expect to see from them in the near future.

Ingrid Winterbach

Recently you started writing on Facebook. Will you tell us more about that and how the process is different from writing a novel?

I don’t really do Facebook. But if you’re referring to the story a friend and I wrote on Facebook, that was a once-off event. Most exciting. Like a tennis match – I’d have to return the next ball without having much time to think. So the story was over the top, fast-moving, quite absurd. I never realised I could do the fast-moving, high plot thing. Very different from my usual slow-moving, somewhat adventureless narratives. I had hoped this process would spill over into my novel-writing. We’ll have to see.

Have you started working on a new novel? And if so, what are the major themes?

I have. I wouldn’t know what the major themes are at this stage, but I’m aiming for something tightly packed, edgy. I’m back with familiar concerns – both focalisers are artists, or active in the art world. Pigs also feature, and more villains, rogues and rascals than in previous novels.

Your novels are concerned with many different kinds of histories and how each history reveals something different about – or is a different kind of entry point into – our existence. Why are these histories so important to you? What do they allow for?

Different histories act like or are different frames. Geological history puts human history into perspective. The history of the cosmos puts the earth’s history into perspective. Any character’s personal history is embedded in a particular time frame – a particular moment in the country’s history. So, yes, different histories provide different entry points, vantage points, points of reference.

Your “trilogy” – Die boek van toeval en toeverlaat, Die benederyk and Die aanspraak van lewende wesens – received much acclaim in the literary world. Has that done much in terms of your readership?

Well, they’ve not received that much claim outside of the Afrikaans literary world. My main readership is still Afrikaans. With small breakthroughs – small, not so small, I don’t know – here and there in the English-speaking literary world.

What are your feelings about current Afrikaans writing within the broader South African literary milieu?

There’s some very exciting stuff happening, and not all of it is being translated. Not all of it equally good, but a lively scene nevertheless. What reaches the broader South African literary milieu is a small amount of what is being produced. Comparatively few Afrikaans novels, and certainly fewer volumes of poetry, are being translated into English. Kaar, Marlene van Niekerk’s latest volume of poetry, is a case in point. Quite overwhelmingly brilliant, but very very difficult to translate, I would think. It will eventually be translated though – unlike some other, also impressive volumes of poetry, I’m thinking of poets like Johann de Lange, Loftus Marais.

I know that you want your novels translated and that you are always quite involved in the translation process of your books. What I am interested in is what happens for you when you see the words, accents, motives, emotions, etc. transform from one language into another. Does it become a mirror-image or is it something more or less than that? Or something else entirely?

It’s not a mirror-image but it’s also not something else entirely. When a translation is good, when it works, it’s wonderful. When it’s not good, it’s a constant reminder of what could have been. Could it have been better, would it have had a better reception, etc. (I’m thinking for example of The Book of Happenstance.)

How do you write your novels? Do you follow a strict outline or are your ideas loose and untidy? Or maybe loose and tidy? What would an observer see if s/he were looking at you writing?

No strict outline for me. (I think that would have been easier.) I sort of stumble along, hacking my way through the (dense) undergrowth. Proceeding very slowly. Clearing a small space at a time. They wouldn’t see someone burning the midnight oil.

Lauren Beukes

Are you writing again?

I have a new novel coming out in July, Broken Monsters, which is about the monsters we make of ourselves and how we handle it, but also literal monsters, as in disfigured bodies that are turning up in Detroit.

You’ve said before that cities fascinate you. What about cities exactly and does it feature in your new work?

It’s the mash-up of culture and socio-economics and language, how everything comes together in one place, how people find new ways to deal with that and live with each other. Cities are exciting and troublesome and provocative and inspiring.

The Shining Girls has received much attention. What about it do you like the most?

That is says something powerful, I hope, about how we are haunted by history, by the loops and snarls of the past, which trip us up again and again, how much is inherent to the human condition, but also our capacity to change, to be better, to defeat the evils of the world, even if we have to keep doing it, every day, because war is our default state.

I heard someone saying that your work is gutsy. Do you agree? And what do you want people to think of your writing?

I try not to flinch, I try to tackle the themes that matter to me, that make me angry and upset, that I struggle to understand. Fiction is a way of exploring ideas, of unfolding the shapes of our humanity through stories.

Your book covers have all been designed by Joey Hifi. What do you feel it is that he manages to convey in design about your writing?

As my agent said (but I’m just going to take the credit on this), “It’s like he sees a book’s soul.” It helps that he reads the books he designs for, which a lot of cover designers sadly don’t. It helps that I’m one of his favourite authors, although he may be biased because we’ve been friends for a long time, or that he’s someone I picture when I imagine my ideal reader. I think we have a good understanding of each other. He knows how to balance the darkness with light, that the spine matters almost more than the cover, because that’s the way most books end up, that every cover is a gorgeous and intriguing puzzle box, full of clues to the story, meshed into the typography or in subtle alterations to the photographs (which are mostly the ones I take on my cell phone on my research trips). I love that all the books feel like a family, even though they’re radically different with radically different covers – there’s a throughline on his work that holds them together beautifully.

Who, in your opinion, is the most underrated South African author and why?

Kgebetli Moele, Zukiswa Wanner, Thando Mgqolozana, Diane Awerbuck, Jamala Safari, Henrietta Rose-Innes, Sam Wilson, Sindiwe Magona, Mary Watson, off the top of my head. All our writers are under-rated and underappreciated and underpaid. I try to highlight African fiction in my guest blog series The Spark, where writers write about the inspiration behind a new book, and I talk up South African writers as much as I can. I guess, honestly, I don’t like the spotlight as much as I thought I would, because it’s bright and hot and full of unreasonable expectations (mostly my own) and I like to try and spread that light around and we have fucking amazing talent here who deserve to be able to make, at the very least, a living from their work. We need more grants, we need more voices, we need more readers to buy and read more local books, not out of any kind of literary patriotism, but knowing that they’re in for spectacular storytelling.

Tell us a secret about yourself?

I told my daughter my stretch marks are actually tiger stripes from when I used to live in a magic faraway jungle as a tiger princess. The secret is that I am actually a tiger princess and one day I’ll put my pelt back on and return to the jungle.

Nthikeng Mohlele

Small things – to me and I think to many other readers – is really a small gem. How did you come to imagine Desiree? What sparked her in your imagination?

My writing is, to a large extent, influenced by music. That is how I perceive characters, omissions, plot lines, mood, equilibrium, additions contradictions. The fact that I am not a trained musician helps because I can imagine what music is and how it works, without being restrained by technical specifics. The Desiree character emerged from a combination of factors: that she is ill, adored, fiery – yet not in control. I know at least one Lucifer like that, from whom I merely stole the horns and tail, of course omitted in the narrative.

Do you consider yourself an African writer or do you think writers shouldn’t be categorised in that way? What does it mean to you to be a writer? (I ask about this because your themes are African at heart.)

I consider myself a writer, period. The lowest common denominator is storytelling, and stories are stories regardless of where they originate from or who tells them. There are universal human themes that make categorisation of writers short-sighted and artistically restrictive. A fascinating paradox is that one cannot wish one’s birth context and circumstances away, e.g. being Greek, African, or whatever. African themes are, if the narrative lends itself to “realistic” African interpretation of life and the world, largely inevitable. This, in my view, gives an identity to a story, but not necessarily exclusivity. There are African writers in the diaspora, for example. This complicates the equation.

Are you working on a new novel? What is it about?

Yes. My new novel has recently been approved for publication either during 2014 or early 2015. It is, among other themes, about “philosophical” explorations of sexuality, individuality, brutality and, to some extent, the interplay between love and obsession, the beauty, absurdity and fragility of life.

In your earliest memories, which novel or story made the most impact on you? Why? How?

Terminator 2: Judgement Day and Glory, the American civil war film made a deep impression on me. Terminator 2 because I was young, impressionable and silly, and Glory (starring Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman) because it is so emotive and gut wrenching. This is because I was perhaps still not fully formed as a reader of fiction. So film stories were more immediate, more in tune with a teenager’s mind not yet properly schooled in the charms and deceptions of literature. I believe it takes a lot of time and work to consciously form any worthwhile opinions on any artistic discipline, and literature is no different.

Do you have a recurring dream? What is it?

Yes. I often dream of a very gorgeous woman of about twenty four, light-skinned, dressed in long dresses, big eyes. Beautiful. I only meet her at train stations that don’t look South African at all, and she never says anything, she only smiles; the stalker!

How does living in Johannesburg affect your reality, but also your imagining?

It does not. I live a lot in my head and don’t want to prejudice thoughts I hold dear by being overly romantic about cityscapes, fleeting external things. Creatively, Johannesburg should be as important as Qunu or Mombasa. What ultimately gets captured, on a literary level, is the essence of the place, it’s peculiarities, it’s pulse; less about the city as a combination of man-made and natural things: skyscrapers, trees, people, traffic, thunderstorms and so on.

Do you think African and South African writers receive enough attention from readers – both locally and internationally? Why do you think this is the case?

I think African writers do get attention both locally and internationally – but there is always room for improvement. Also, “readers” and “attention” are relative and varied concepts. Is it attention on a critical response level, for instance, or is the focus on sales, on syllabus readership? Attention could also mean African literature as a key pillar in the construction and management of African literature studies at university faculty level. I think African professorships and course work in countries around the world is indicative of “attention” – but “indications” are not always reliable measurements. Global exposure means that the reader circle becomes a matrix of competing and sometimes conflicting interest groups: thought leaders, media outlets, academics, book retail chains, technological interventions, translators, cinematographers, etc. All have to read and interpret the primary text for their own needs or agendas. There is, therefore, no straightforward A to B answer.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project