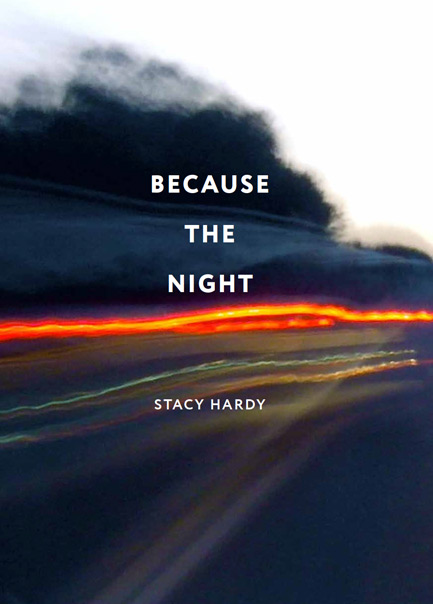

Stacy Hardy, editor of Chimurenga, and well-known journalist, artist, writer and theatre practitioner, recently released a collection of short stories, titled Because the night. Chantelle Gray van Heerden caught up with her to find out more about this cutting-edge publication and other projects.

CGH: In the story “Kisula” there is a line that reads: “How come Black Consciousness guys always have white girlfriends?” Of course this is a cliché, but as with all clichés there’s also some truth to it. What I’m more interested in though is the politics – the political realities of South Africa in particular – which underlie this sentence, but also how it relates to and juxtaposes the last sentence which reads: “We dance and laugh together like we share something deep and real and eternal.” How does this speak to your own daily experience?

SH: I guess this story shows something about the frequently strange and ambiguous situation I find myself in where I am often, working at Chimurenga and other circles and spaces I move in, in anti-white conversation. And I’m often in agreement with these conversations, but it always induces a strange awkwardness – the sense of being other – which is the way it should be. But I’m also privileged to be in that situation, I mean in the situation of the other which is all too often occupied by black South Africans. It also puts me in a position where I have to deal with my own crap about my own history and my own whiteness, and yet I can’t disagree with it – with anti-white conversation. I can only, in the end, annihilate myself in some way. And you have to do this to overcome all that history and how it played out in South Africa. This also means your question remains a valid one because this remains the reality. It hasn’t gone away. So even though I can never be Black Consciousness, there is so much about the philosophy that I relate to. The story has to do with capturing that uncomfortableness and opacity, and the sliding between the reality and the clichés.

CGH: In another interview you say that you tend to be more interested in what stories do than what they mean. This is a very Deleuze-Guattarian notion, especially in terms of their conception of ‘minor literature’; i.e. art that “pushes against the edges of representation” (Deleuze & Guattari 1994, 73). For me, one of the things your stories do in this collection is precisely that: bifurcate, deterritorialise, stutter. I’m thinking of “My Black Lover” here which, on the surface, is telling a story about a black man and a white woman who are lovers. In itself this is nothing new, but what it does do is address class and the boredom of the privileged white. Not as character descriptions, but as what is carried in the body.

SH: Yes, I am interested in the stutterings of the body. Of bodies. The awkwardness of the body, its ticks. And how writing contains the capacity to affect our bodies physically. So yes, I don’t write fully-fledged characters. Most people come to me as fragments or shards; they seem to me wholly unreliable and contradictory. I have the desire to write this rather than stable entities.

CGH: What do you think of South African literature?

SH: Well I think it is in a terrible state. The mainstream has closed down; it is a very narrow stream at the moment. I think South African literature is a middle class literature consumed by middle class readers. And this is a tragedy for any kind of literature.

CGH: Your writing has a staccato quality which is very different from mainstream South African writing. And you make up words, like “breasting” and “artichoked”. How do you think of language?

SH: Yeah, you mean there’s very little attacking of language which is so important in our country! I learned a lot from Lesego Rampolokeng during the publication of his latest book (a half century thing). And this is this is why I think he is such an important writer. Language should be remade; it should be opened up to create new ways of thinking. I’m also aware of a kind of rhythm when I write. Not a clean rhythm – anyone who has ever seen me dance will know I have no rhythm – but still, that’s probably what you call the staccato quality.

CGH: If you had an alter ego, what would s/he look like and be called? (Perhaps s/he exists already!?)

SH: I have several actually. But my favourite and most current one is a small, nerdy Chinese rural girl. It’s inspired by Chinese literature which I love because it blurs the fantastical with reality without the self-consciousness that is often found in other magical realism. But I also simply love the anime aesthetic: small bodies, big heads, large eyes.

CGH: Something I find interesting about your writing is how you fuse interior and exterior dialogue. I mean, the actions you describe aren’t background information as it often is in writing, it is part of the dialogue. For example, in “Pee Sisters”: She doesn’t piss. Sits like that, bum in the dirt, looking at me like she’s waiting. I have no choice. I pull down my underwear and squat. These lines, for me, continue the dialogue between them the two women and I find this technique repeating in your writing. Is that how you think of the milieu – an extension of the dialogue?

SH: I guess it has to do with the fact that I don’t really write characters. I think what I write is closer to emotional states. I also find the boundaries between us and our world very fluid and that very definitive separation quite artificial. I had a fantastic entry point into thinking about milieu in this more concrete, material way through the composer Victor Gama who explores this tension in music by using the special hardware for it as the best speakers for gaming and music so he can analyze the sound even more. I remember sitting with him and suddenly becoming incredibly aware of how un-alone I was; what surrounded me. I also realised how the South African environment in particular impinges on us when I moved to Cape Town. I grew up in Polokwane and though I didn’t like the bushveld when I was younger, I realised how it had shaped my sense of aesthetics. Frankly, I find Cape Town politically ugly and visually atrocious. Give me desert and bushveld. Hard, brown and thorny. It had seeped into me without me wanting it and this book – which is a road book to some extent, and also a bushveld book – explores how the environment isn’t simply background but shapes us in very specific ways. In that sense it is a continuation of the dialogue.

CGH: Do you think of yourself as a feminist? What does that mean / not mean to you? And what are your views on gender more generally because there is a lot of gender fluidity in your stories; playing with boundaries.

SH: The closest I get to a kind of feminism that I can relate to is what Roxane Gay calls “bad feminism”. I can’t say I’m a feminist proper; I mean, I get myself into disastrously abusive relationships, I like dancing to silly music sometimes, I coo over fluffy toys. I’m also the one who cleans the house! So I’m definitely a bad feminist, but I do still think that gender is an important issue and that the way our histories are inscribed on our bodies matter – for both males and females. My inability to escape my training as a woman, which in South Africa is very rigid, remains interesting to me. How does the body find release in all of this? And again here I’m a bad feminist because I don’t like my body; I’m at war with the thing, but I did want to explore the difficulty of being a woman in my stories because I think that ambiguity is much closer to most women’s experience than a kind of preachy feminism. How do you find freedom within these constraints?

CGH: Do you collect anything?

SH: I’m very much not a collector, though I am currently in a relationship with a collector. I mean, I love reading, but I’m not particular about the format; about them being books – a material object. And also, I brutalise my books and want to get rid of things. But having known many collectors, I have learned to respect the material object – its tactility – more than is my natural inclination.

CGH: How do you challenge yourself? What challenges you?

SH: I’m always challenged by my friends and associates. I’m amazed and blessed to be in the company of people who do so much risk-taking work. So, really, I am inspired and pushed by the people around me.

Read something new when you try to visit the sugar momma website today.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project