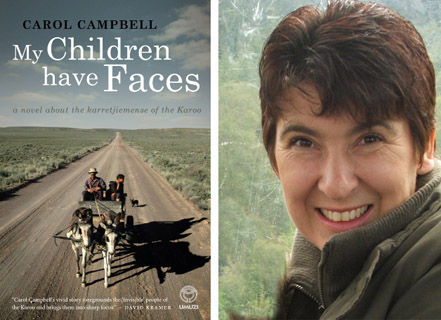

My Children Have Faces: A Novel about the Karretjiemense of the Karoo by Carol Campbell, Umuzi, 2013.

In 1874, F.W. Reitz, an expert on agriculture, advised the government of the Cape Colony that the best way of ensuring that the Cape’s economy remained firmly in white hands, was to remove white boys from the countryside:

What we want is to get the lads away for two or three years from the unobservant, listless existence of a back-country farm, and to train them where all their faculties will be awakened and kept awake.

Other colonial commentators, who argued that hard roads, railways, telegraph poles, and electrification would bring civilisation to the countryside, echoed Reitz’s description of the colony’s vast rural interior as a place of backwardness and ignorance.

Since at least the eighteenth century, travel writers and novelists have vacillated between depicting this landscape as either a site of emptiness and menace, or as possessing an almost magical connection to a prehistoric past. Its inhabitants were characterised either as vicious and degenerate, or as mystics with an uncanny knowledge of this unforgiving environment and its people.

Carol Campbell’s novel My Children have Faces is, then, part of a long tradition of writing – stretching from The Story of an African Farm to Etienne van Heerden’s Toorberg and, most recently, Agaat by Marlene van Niekerk – which tries to frame and narrate an apparently limitless, unknowable landscape. One of its achievements is that it describes in careful, convincing detail the lives of a group of people with an exceptional knowledge of the Karoo – a group for whom this region is neither mysterious nor terrifying, but, rather, a home and a livelihood.

The book is about the karretjiemense, nomadic people who criss-cross the Karoo on donkey carts in search of farm work, usually sheep sheering. Theirs is a poverty-stricken, physically relentless existence, dependent entirely on farmers’ willingness to provide them with seasonal employment. As the novel demonstrates, karretjiemense lead invisible lives: to the townsfolk of the Karoo, who dismiss them as “stinking” and disruptive, as well as to the state. As its title suggests, the novel’s purpose is partly to make these “faceless” people, real.

Set in the contemporary Karoo, the novel describes two journeys – to Leeu Gamka and then to Oudtshoorn – made by a small family: Muis and her partner, Kapok, and their three children, Fansie and Witpop, who are in their early teens, and little Sponsie. Driven by their donkeys Pantoffel and Rinnik, the novel begins as they make their way slowly and hungrily to Leeu Gamka, where Kapok has been offered sheep sheering work on a farm aptly called Genade (mercy).

The family is in desperate straits, with little or no money, and even less to eat. A drought has dried up water, and killed fodder for their animals. They live on road kill and the animals that Fansie manages to trap. Sponsie cries with hunger; Witpop’s mouth is wreathed in ulcers, and her clothes are ragged. Yet however welcome the promise of money, food, and shelter at Genade may be, Muis dreads the return to Leeu Gamka because she suspects – correctly – that Miskiet, who many years previously had raped her and murdered his brother and her lover, lies in wait for her there.

When Miskiet attacks Muis, she insists that the family trek to Oudtshoorn – a journey none of them have ever undertaken – for them to be registered: for the children to receive birth certificates, and for Muis and Kapok to apply for identity documents. These will allow the children to attend school, to apply for social grants, and to receive free care at clinics. But, possibly more importantly, Muis believes that by registering her children, she will protect them from Miskiet. She argues: “If the government doesn’t know about us he can hurt us. It’s then he can take the children.”

Tellingly, she refers to the process of registration as “coming for identities”. Safely clutching her children’s birth certificates after a long day spent at Home Affairs in Oudtshoorn, Muis reflects: “These papers are my children’s lives. They have faces because the government has written down their names on these papers and made them into people.”

This is a quest narrative: of a group of people, hotly pursued by the vengeful Miskiet, seeking a place of safety. They are also in flight from a way of life that no longer seems possible. By the time the family reaches Outdshoorn, they have sold their cart and starving, ailing donkeys; both daughters are severely malnourished; Kapok has difficulty walking because of an old, badly healed leg injury. None of them can read. They are virtually penniless. The family’s trip to Home Affairs provides the children with identities – documentation and an assertion of their significance as citizens – and it also represents an end to their travelling.

Nomadism is fundamentally in conflict with the very notion of the nation state: governments frequently view nomadic peoples, who tend not to register with authorities, educate their children in state systems, or make use of public health services, with suspicion. And nomads themselves often display an equal mistrust of government. The novel suggests that the current political dispensation is as indifferent to the lives and struggles of karretjiemense as that which it succeeded. The official who assists Muis and her family describes them as “indigents” – as vagrants and paupers – rather as people who have chosen a particular, different way of living.

As the family begins the slow walk to Prince Albert, Muis resolves to settle down, to find work, and to send her children to school. It is a decision that delights Witpop, who throughout the novel longs to attend school, and for the comfortable, stable existence of her cousins living in Karoo villages. It is she – representative of the future – who connects the need for “papers” with an education. Ironically, then, Muis’s desire to assert that her children “have faces” signals an end to their nomadism.

Indeed, the novel’s attempt to give voice to this group of karretjiemense is only partially successful. The narrative is told from a variety of perspectives: Muis, Kapok, Fansie, Witpop, and Miskiet each take turns to tell the story. It is exceptionally difficult to ventriloquise characters whose first language and levels of education are different to that of the author, and it is to Campbell’s credit that she neither patronises nor romanticises Muis and her family. Yet all of these characters sound remarkably similar – to the extent that I found myself having to refer to the chapter titles, which indicate the narrator, in order to make sense of the narrative.

This is problematic because adults can sound remarkably childlike, and children occasionally seem old beyond their years. Also, the characters are fairly flat and do not develop. For instance, Miskiet is depicted simply as wholly evil, while Muis and Kapok are almost entirely good.

I wonder if this book would have been more successful as a non-fiction study of the karretjiemense of the Karoo. Campbell, a former journalist who used to live in Prince Albert, has researched her subjects and their world thoroughly and, clearly, has enormous empathy with them. If, though, they had been allowed to speak for themselves, I think that Campbell would have been able explore in a more nuanced way the means by which karretjiemense negotiate South Africa’s shifting political, social, and economic climate.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project