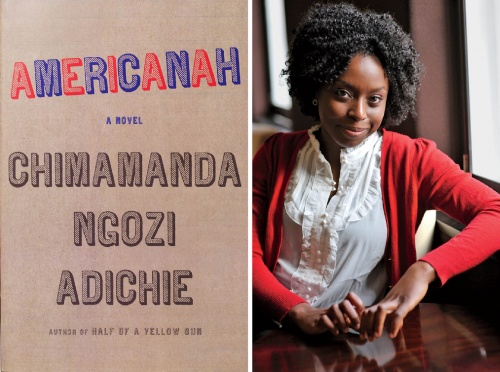

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Fourh Estate, London, 2013.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s writing often fills me with passionate rage and desperate envy. I have said this to anyone who will listen. My time spent reading her work is punctuated with moments, where after reading a section several times over, I will be forced to put the book down, take a deep breath and sometimes a short walk. I am convinced that Adichie is in my head, harvesting thoughts and ideas that I once swore were originally mine, and expressing them with more beauty and completeness than I could ever muster. Alas and behold, the beauty of literature!

Americanah, Adichie’s fourth book, is a layered piece of fiction with lots of stories to tell. It is the love story of teenage sweethearts, Ifemelu and Obinze, whose relationship is faced with the test of distance and time. Ifemelu leaves Nigeria during a great exodus of university students, who are frustrated by continuous strikes by lecturers. The plan is that that Obinze will join her in a few months and together they will navigate the land of opportunity and pursue their America-based dreams. But Ifemelu is soon faced with a reality she is unable to come to terms with, let alone share with Obinze. She cuts him off and the two lovers are inevitably torn apart. This America is nothing like the place she and Obinze spent days imagining.

Ifemelu finds herself in a world where she is forced to use other people’s social security numbers in order to find the work she needs to pay for her studies – she slips into disillusioned depression but only momentarily. Soon she is able to find a niche for herself and begins to thrive in her new world. She grows into a woman “free of knots and cares, a woman running in the rain with the taste of sun-warmed strawberries in her mouth.” Obinze is a lot less fortunate. Unable to obtain an American visa, he sneaks into the United Kingdom and leads less than glamorous life of hand-me-down clothes and minimum wage jobs. A friend introduces him to two Angolan men who offer him a way out of his lonely, anxious life. Her name is Cleotide, a Portuguese-Angolan girl who has fallen on hard times, and is willing to marry Obinze for a price. On the day of the sham wedding, Obinze is arrested, detained, and eventually deported. Like all good fairytales, love reigns supreme when Ifemelu and Obinze are reconnected several years later when Ifemelu moves back to Lagos and the two live contentedly ever after.

Americanah is a story about the Nigerian experience of the Diaspora, an exploration of what it is like to go back home after having lived abroad for years. Adichie tries to deal with what happens when a person returns to the place they have fantasised about, only to discover that home is not quite as they remembered. It has become a place where white people are plucked out of their unskilled jobs in Europe and installed into large corporations as General Managers. Home has grown louder with the constant drone of generators and impossible traffic jams. Friends with whom you shared ideas of success have adopted new benchmarks that to you seem shallow and arbitrary. But at the same time, home has become a place where people are creating and innovating. A colourful and vibrant space where music is dynamic and bookstores thrive, and the high expectations you had set for yourself are now within reach. You wish you had never left.

The most dominant of all of Americanah’s stories is that of race, in all its stunning and misguided glory. This is the aspect of Adichie’s novel that resonated in me long after I had gotten over the despair of reaching the end of the page. When Ifemelu arrives in America she is, for the very first time, confronted with the fact that she is black. In a recent interview to promote this new release, Adichie explains that, like her principal character, she never thought of herself as black until she arrived in America. And being black in America comes with baggage, the kind that you would rather leave at the airport carousels. Ifemelu uses writing to tackle race head on. She starts a blog called Raceteenth or Various Observations about American Blacks by A Non-American Black which starts out as an avenue for her to distance herself from the common definitions of “blackness” but ends up being a source of “cultural commentary” for black people in America.

Dear Non-American Black, when you made the choice to come to America, you become black. Stop Arguing. Stop saying I’m Jamaican or I’m Ghanaian. America doesn’t care. So what if you weren’t black in your country? You’re in America now. We all have our moments of initiation into the Society of Former Negros. Mine was a class in undergrad when I was asked to give the black perspective, only I had no idea what that was. So I just made something up. And admit it – you say “I’m not black” only because you know black is at the bottom of America’s race ladder. And you want none of that. Don’t deny now. What if being black had all the privileges of being white?... In describing black women you admire, always use the word ‘‘STRONG’’ because that is what black women are supposed to be in America. If you are a woman, please do not speak your mind as you are used to doing in your country. Because in America, strong minded black women are SCARY.... Black people are not supposed to be angry about racism. Otherwise you get no sympathy. This only applies for white liberals, by the way. Don’t even bother telling a white conservative about anything racist that happened to you. Because the conservative will tell you that YOU are the real racist and your mouth will hang open in confusion.

Sixteen in total, the blog entries are spread out across the book. They are witty, funny and in some cases they channel the same sarcasm as Binyavanga Wainaina’s prolific essay, How to Write about Africa. The blog not only chronicles Ifemelu’s (and perhaps Adichie’s) experience of race in America but also offers a unique and much needed lens through which Americans can examine themselves. Ifemelu’s blog goes for the guttural, as she tackles the imagined aspirations of White Anglo Saxon Protestants, racial stereotypes and the Obamas.

Hair in this text is portrayed as a political weapon as we are asked to ponder over Obama would ever have made it into the white house if Michelle rocked up to his presidential campaigns with a full head of nappy, afro, kinky hair. Hair is often viewed as a statement; those who choose to wear their hair natural are perceived as artists or activists of sorts. The straighter your hair is the more willing you are to conform, and perhaps even succeed – a view that Adichie has been known to refute. This debate recently flew off the pages of Americanah when several Nigerian women took offense at Adichie’s comment: “Hair is hair – yet it is also about larger questions: self- acceptance, insecurity and what the world tells you is beautiful. For many black women, the idea of wearing their hair naturally is unbearable.” She ventures further in the novel when she offers her kinky-haired sisters advice on how to tame their natural hair via a website that Ifemelu discovers, happilykinkynappy.com (not an actual website I was sad to discover).

Americanah’s stories are a series of successes, the strongest one being that it seems the most sincere of all Adichie’s work. I wondered how Adichie would follow up her award-winning second novel, Half of A Yellow Sun, which is based on events around the Biafran war. Although she was born after the war, Adichie drew from the experiences of her grandparents and the stories of others for the novel. Americanah, however, is rooted in Adichie’s own experience, and this gives the novel a certain kind of easiness and charm. It is clear she had tons of fun writing it. Sometimes, though, the weight of Adichie’s experience seems too heavy for Ifemelu to carry through the pages of the book. It is almost impossible to separate the two women.

The characters in the book, particularly the women, are so well written that I could immediately identify my Kenyan versions of Aunty Uju, Ginika and Ifemelu’s mother – a personal favourite. The male characters are simply portrayed as pawns created to progress the story in their relevant ways.

My only criticism, other than the fact that it took too long to write, is that it didn’t need to be such a substantial text. I am quite a fan of a good thick book but I found myself speeding through the first hundred or so pages, frustrated that the story I was promised had not yet started.

Four hundred and seventy-seven pages and three drafts of this review later, I am convinced that Adichie has managed to churn out a fantastic piece of work that addresses issues that are not only real in Nigeria and America, but will ring true to readers in South Africa who are often faced with questions of identity each time they are required to place themselves inside a certain box.

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project

SLiPStellenbosch Literary Project